⚠️ STATUS UPDATE ⚠️: Forbes contacted Adalytics on March 20th, 2024, after Forbes itself was contacted by the Wall Street Journal (WSJ).

Several days later, Adalytics and other analysts could no longer observe any Outbrain ads directing audience traffic to the "www3." subdomain of Forbes.com.

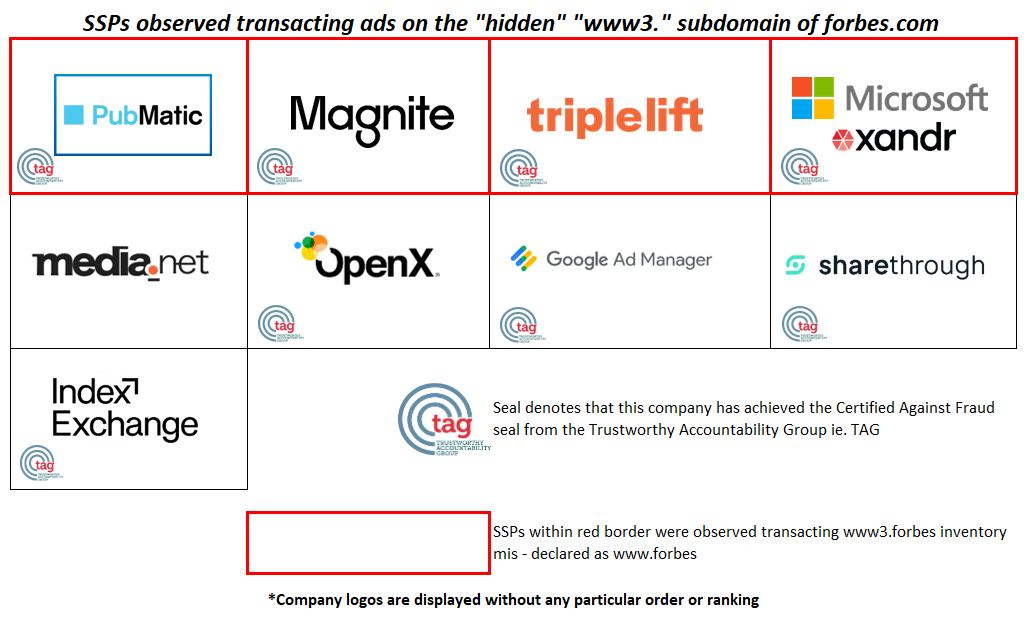

On Friday, March 22th, 2024, at sometime between 8:29 - 8:34 AM US ET, the apparent server-side truncation and mis-declaration of page URLs (“domain spoofing”) submitted to ad auctions via Microsoft Xandr, TripleLift, Magnite, and Pubmatic SSPs via Media.net's Prebid server was no longer observable.

On April 2nd, 2024, the "www3." Forbes subdomain became no longer publicly accessible.

Readers can find archived video recordings of the no longer accessible“www3.forbes.com” subdomain here:

slideshow example - https://www.loom.com/share/9590423e5db34536869aaf226f0c805b

Listicle example - https://www.loom.com/share/4ace9fc864c740518ddb11f957e13569

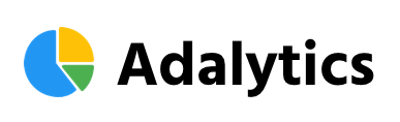

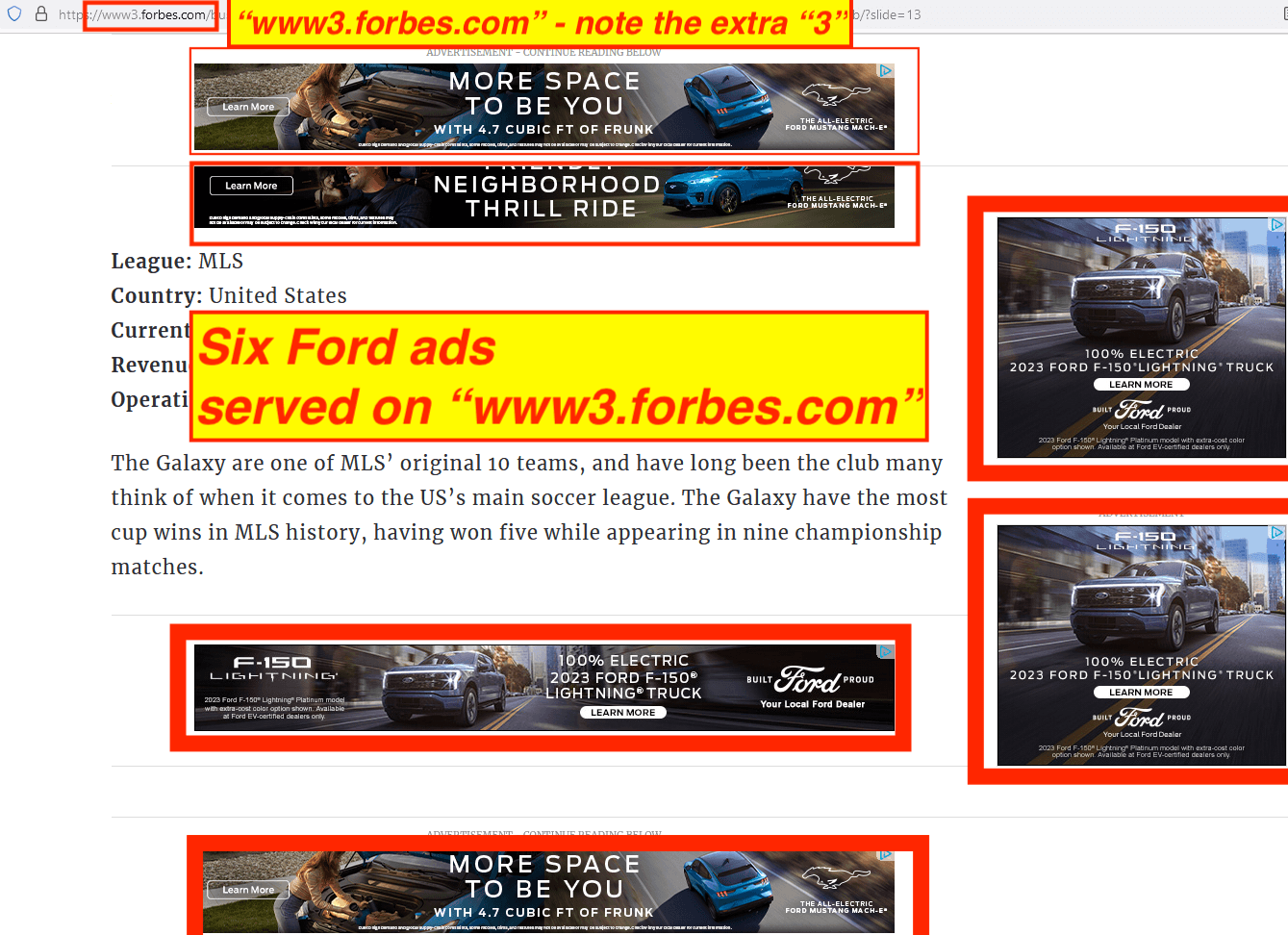

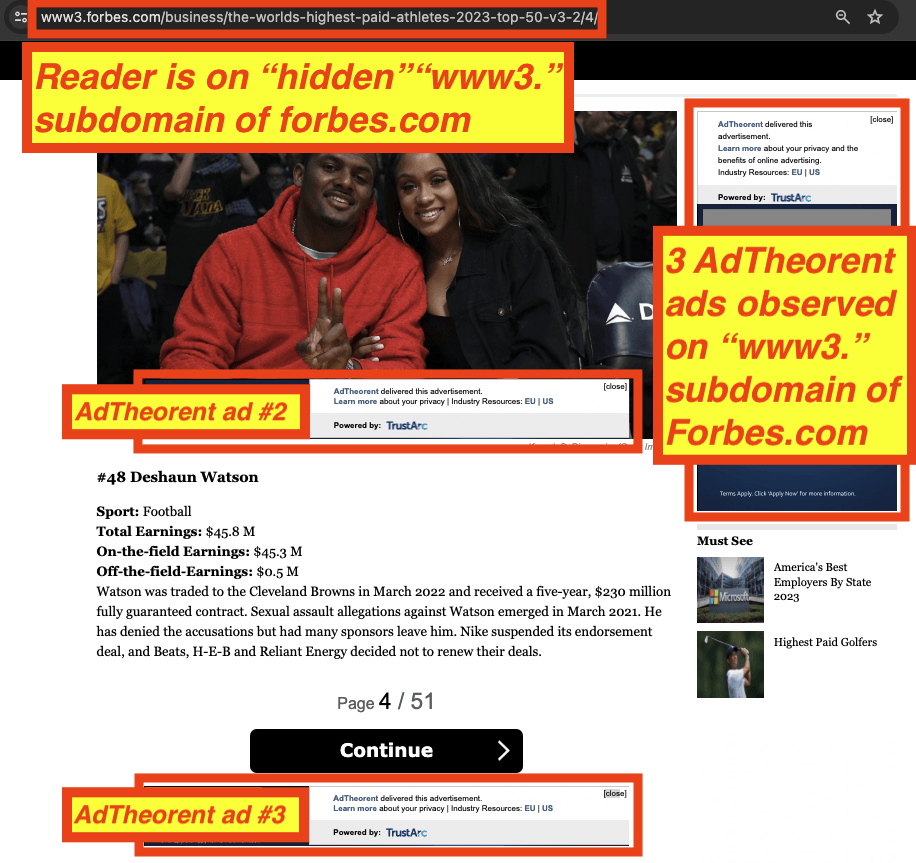

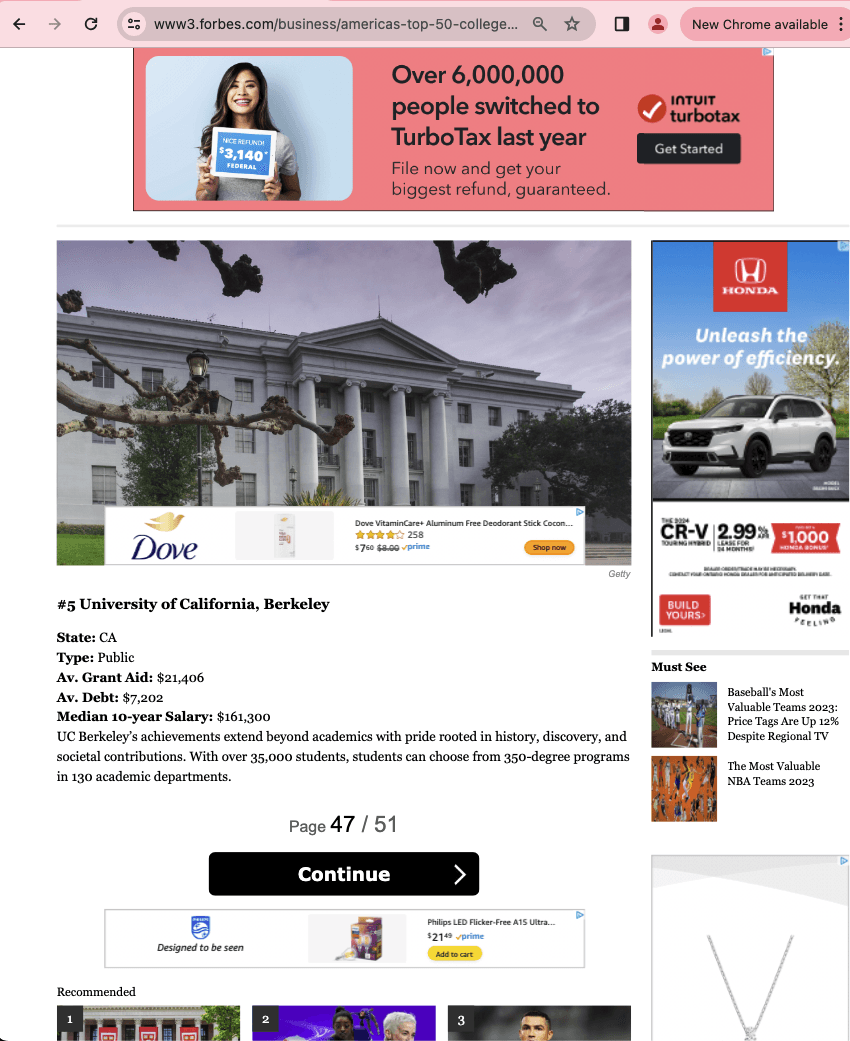

Forbes appears to have set up a dedicated sub-domain - called www3.forbes.com, which appears to have a very different ad serving experience relative to the “normal” www.forbes.com sub-domain. A reader viewing an article on the normal sub-domain may see about 3-10 ads in an article, whereas reading the www3 variant exposes the reader to approximately 201+ ad impressions in a single page view session. Several experts assert that this “www3.” subdomain of Forbes can be classified as “Made for Advertising” or “Made for Arbitrage” (MFA). One consumer was shown 27 New York Times subscription ads and 201+ ads total while viewing a 52 slide slideshow on the “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The New York Times paid an effective cumulative CPM of $60.39 to serve ads to that one consumer.

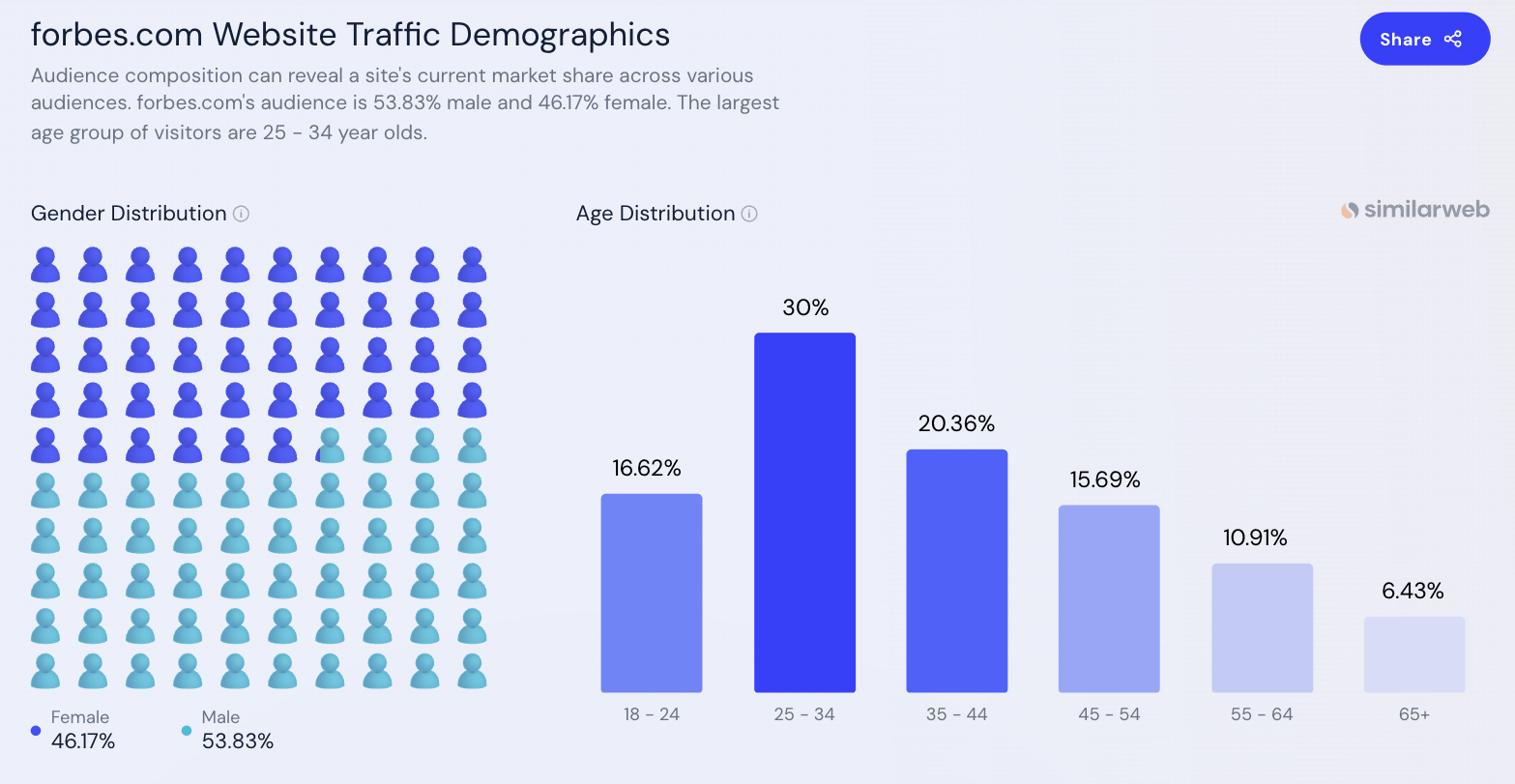

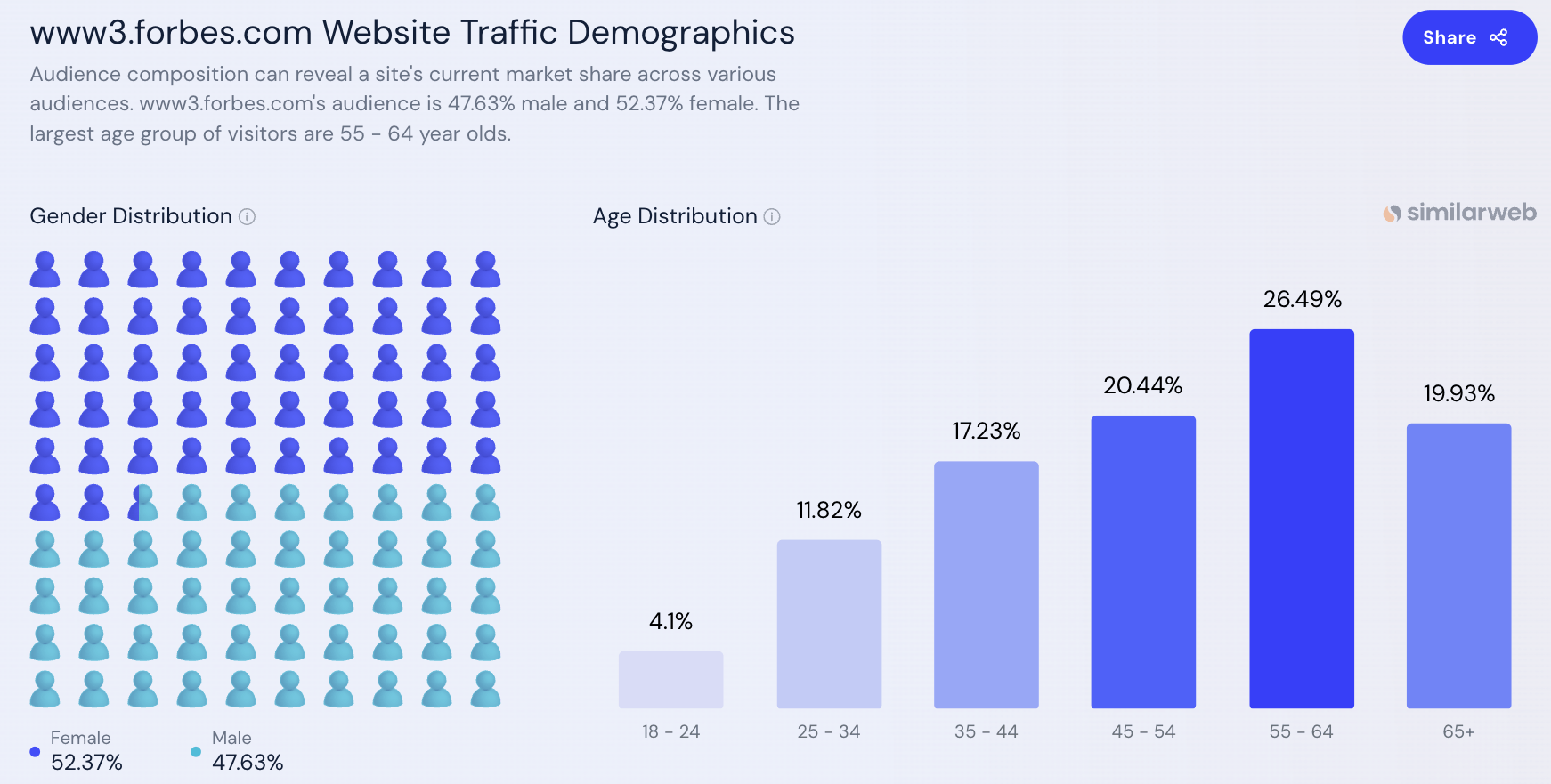

The “normal” www.forbes.com root domain appears to get 90%+ of its readership through organic search and direct page navigation, whereas the “hidden” “www3.” sub-domain appears to source more than 70% of its readership through paid display ads on Taboola, Outbrain, and other paid traffic acquisition sources. Data from website traffic analytics firm Similarweb shows that the largest age group of visitors on the “normal” “www.forbes.com” domain are “25-34 year olds”. However, Similarweb shows that the largest age group of visitors on the “hidden” “www3.forbes.com” subdomain are “55-64 year olds”.

Data from Similarweb show large differences in behavior amongst the audiences of the “normal” forbes.com and the “hidden” “www3.forbes.com” subdomain. Similarweb shows the “audience targeting”, “affinity”, and “browsing interests” of the readers of the “normal” “www.forbes.com” website are predominantly other business and news websites, such as businessinsider.com, nytimes.com, and bloomberg.com. However, Similarweb shows that the browsing interests of visitors to the “hidden” “www3.forbes.com” subdomain include tabloid or other “Made for Advertising” websites.

Forbes does not seem to deploy its subscriber paywalls on the “www3.” subdomain, unlike on the regular Forbes website.

Unlike the “normal” Forbes website, it appears that (for all examined page URLs) Forbes instructs search engine crawlers such as Google Bot and Bing Bot to not index the www3. subdomain's articles. This means readers (or digital media industry analysts) cannot find these specific articles in either organic Google or Bing search results.

Forbes’ website appears to be set up to automatically redirect users who try to open www3.forbes.com to www.forbes.com, preventing the user from reviewing the content on the www3. subdomain unless they input an exact page URL or first click on an Outbrain ad on another website that redirects them to the www3 subdomain.

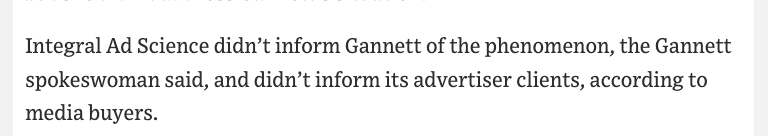

Forbes appears to use the publisher ad verification solutions of Integral Ad Science (IAS), DoubleVerify, and Oracle Moat on the “normal” “www.forbes.com” domain. However, Forbes does not appear to deploy these vendors’ publisher suite Javascript code on the “www3.” subdomain.

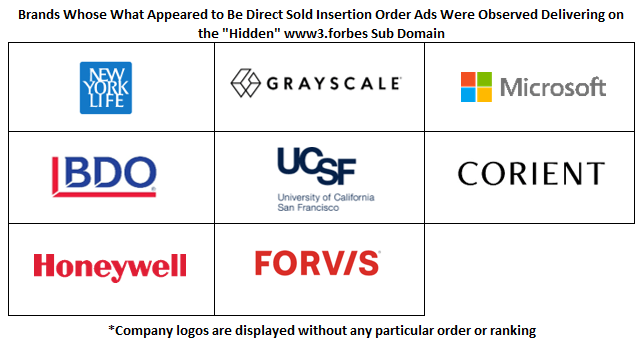

Forbes appears to serve direct-sold insertion order ads from major brands, such as New York Life insurance, Honeywell, University of California, San Francisco, Corient, Fovis on the “www3.” sub-domain. Readers of this sub-domain were occasionally served what appear to be dozens of direct sold insertion order impressions in a single page view session on the www3 sub-domain.

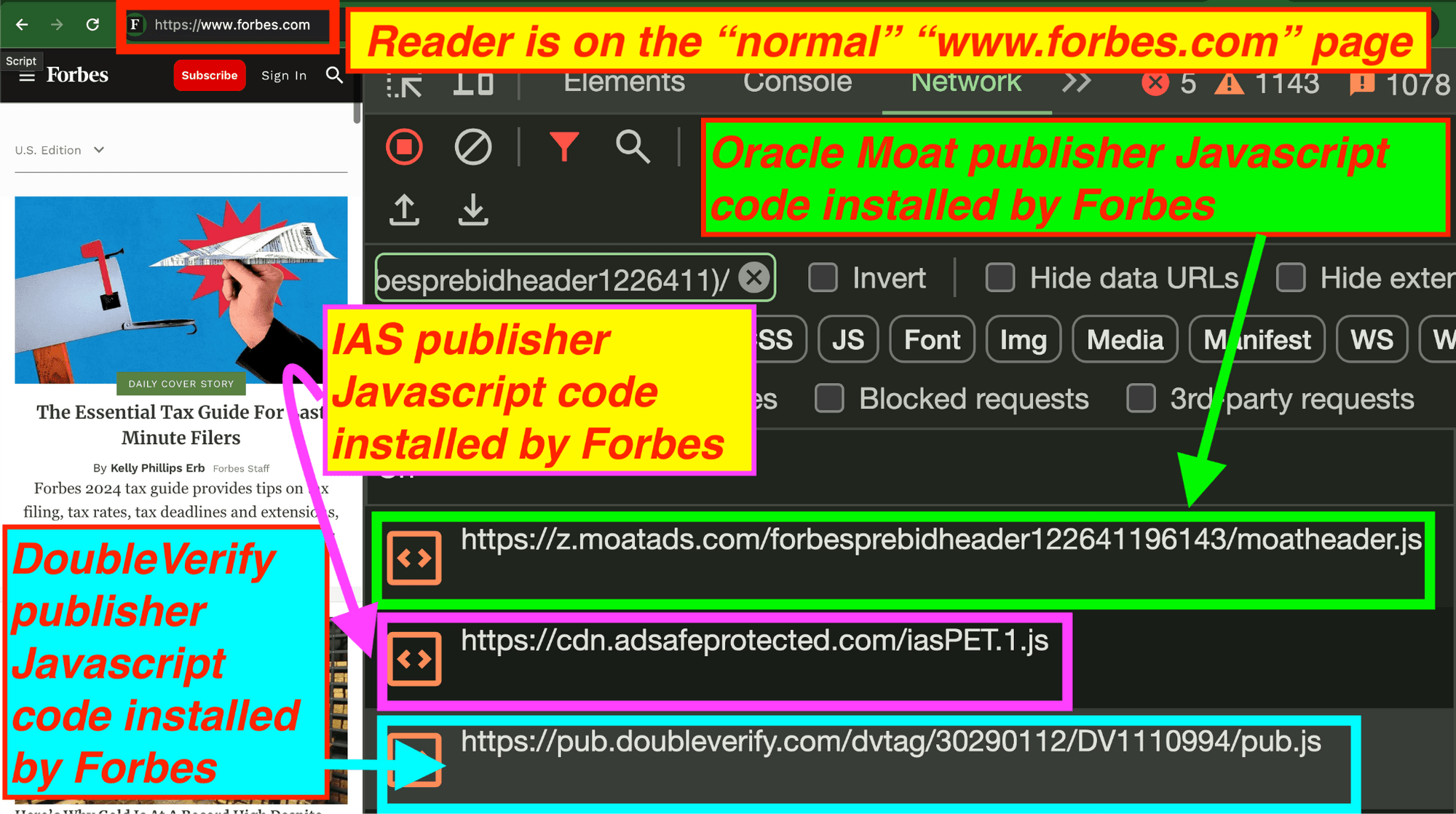

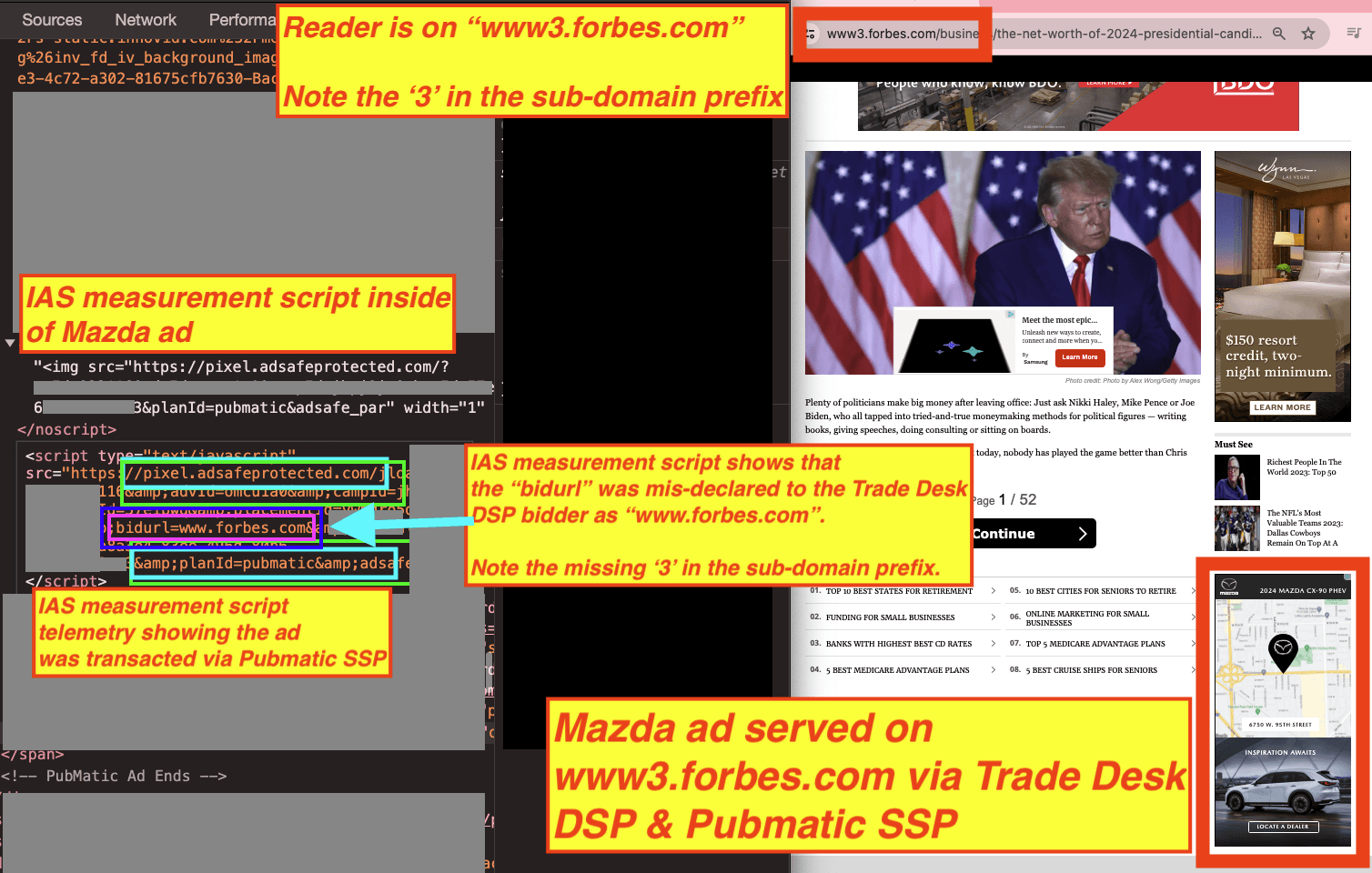

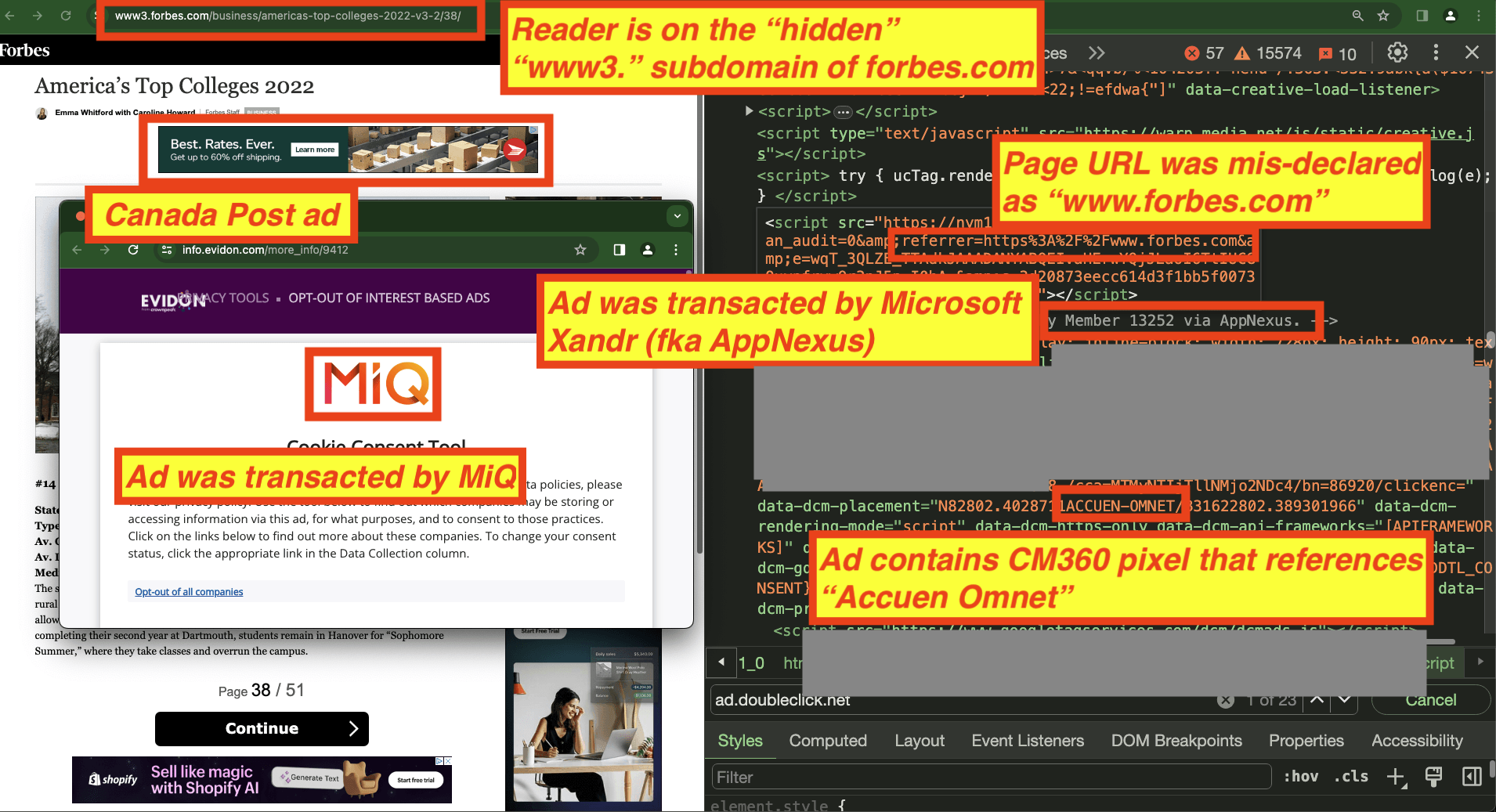

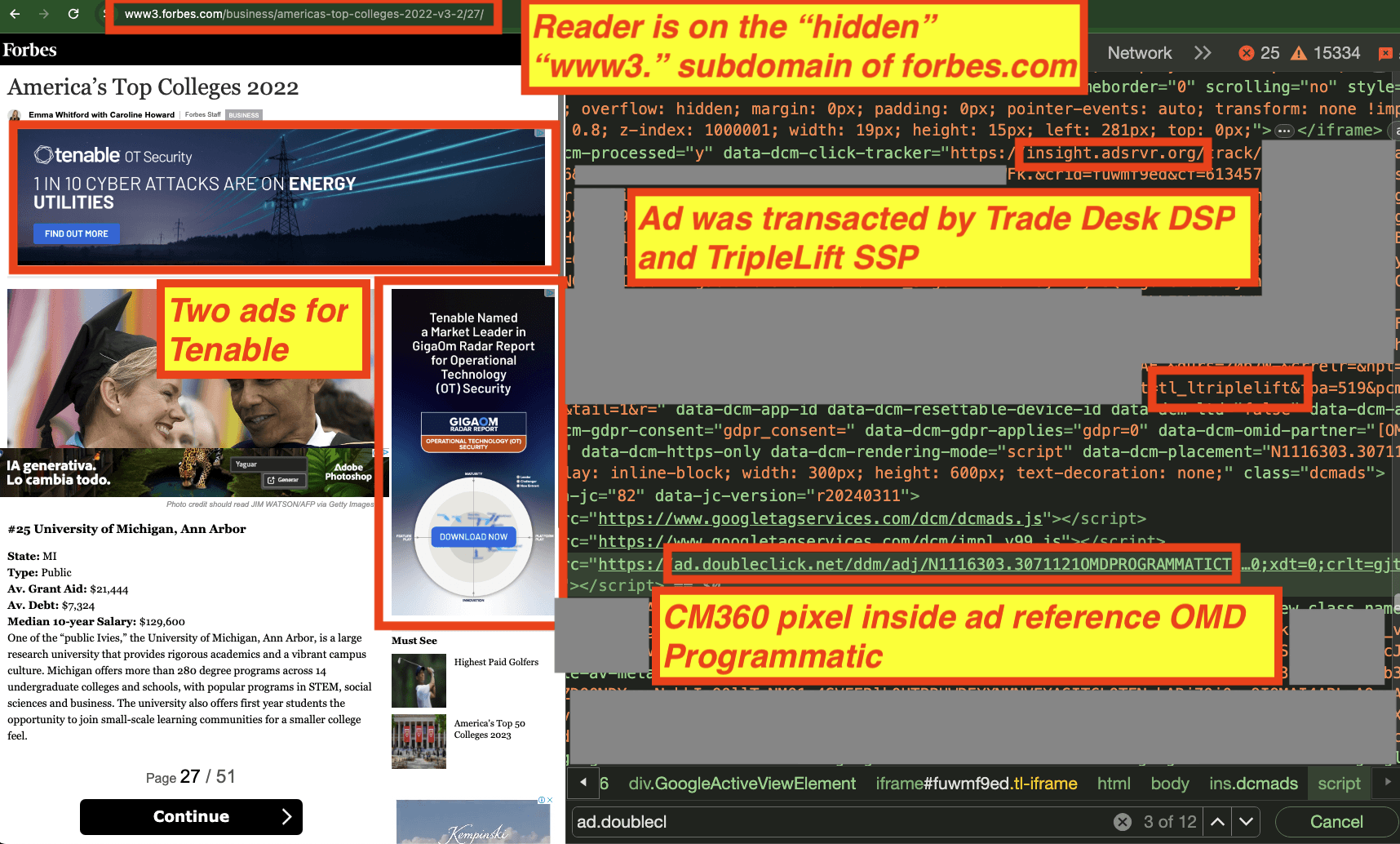

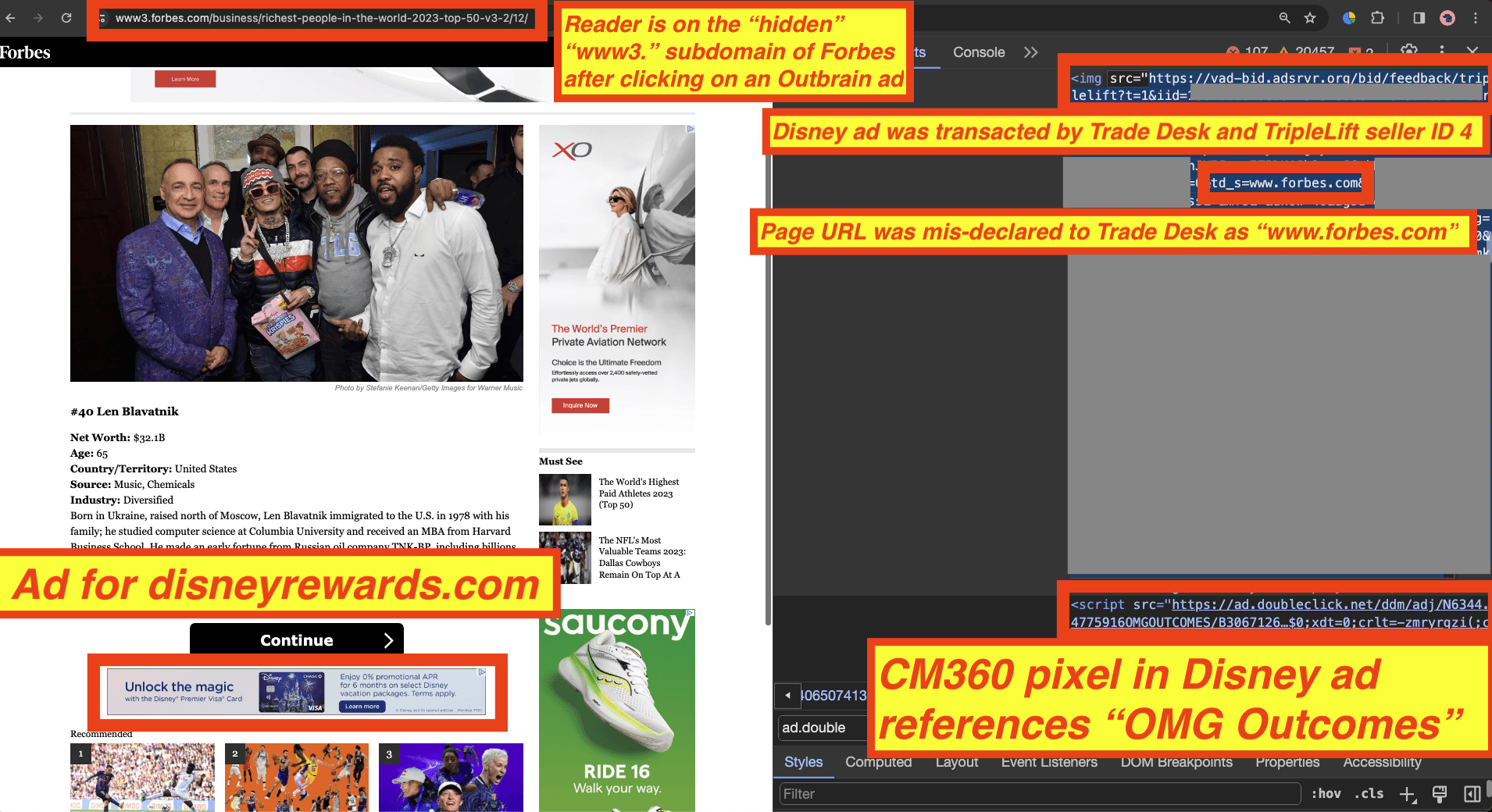

When some ad inventory from the “www3.” subdomain is transacted via server side Prebid, four ad exchanges - Microsoft Xandr (fka AppNexus), Triplelift, Pubmatic, and Magnite - appear to incorrectly relay this inventory to buyers as being served on the “normal” “www.” sub-domain, which some industry experts consider to be a form of “domain spoofing”. Some of this mis-declared inventory was observed transacting via what appear to be Private Marketplace (PMP) deal IDs.

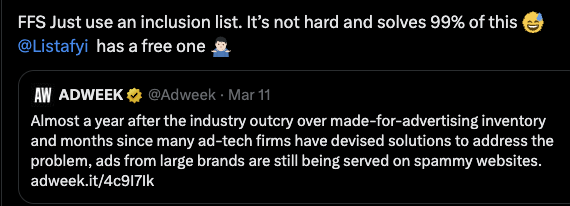

Many SSPs that transact ads on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain appear to have public, written policies that prohibit or discourage certain publisher ad serving practices These include mis-declaring page URL information, excessively refreshing ad slots, or having a large amount of readers visit the publishers’ content through non-organic traffic sources. Media.net, Pubmatic, Magite, ShareThrough, TripleLift, and Microsoft Xandr SSPs’ apparent monetization of ad inventory from the “www3.” Forbes subdomain may raise questions about these vendors’ enforcement of their own inventory policies.

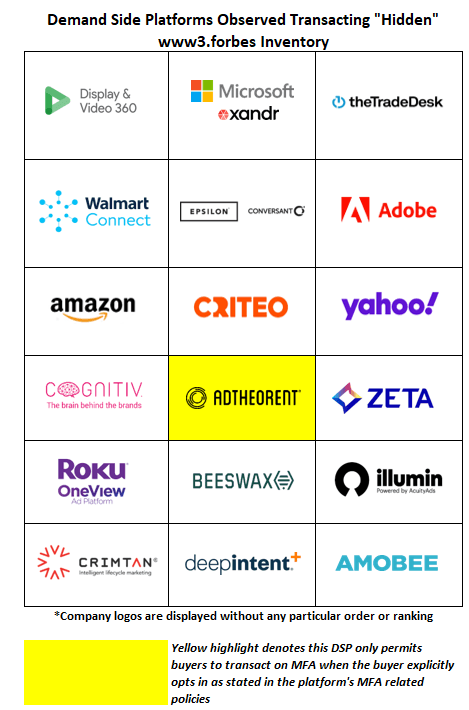

Certain buyers who explicitly block the “www3.” sub-domain were confirmed to have their ads served on this sub-domain through those four specific supply paths. Google DV360 DSP, Yahoo DSP, Adobe DSP, Microsoft Xandr DSP, Trade Desk, Walmart DSP (built on Trade Desk), Publicis-owned Epsilon Conversant, and other major ad buying platforms were observed transacting ads via the mis-declared or “spoofed” www3 inventory. Other DSPs or bidders observed transacting the “www3.” “made for advertising” subdomain include Amobee DSP, DeepIntent DSP, Cognitiv DSP, Quantcast DSP, Centro Basis DSP, Zeta Global DSP, Crimtan DSP, Criteo DSP, AdTheorent DSP, and Amazon DSP.

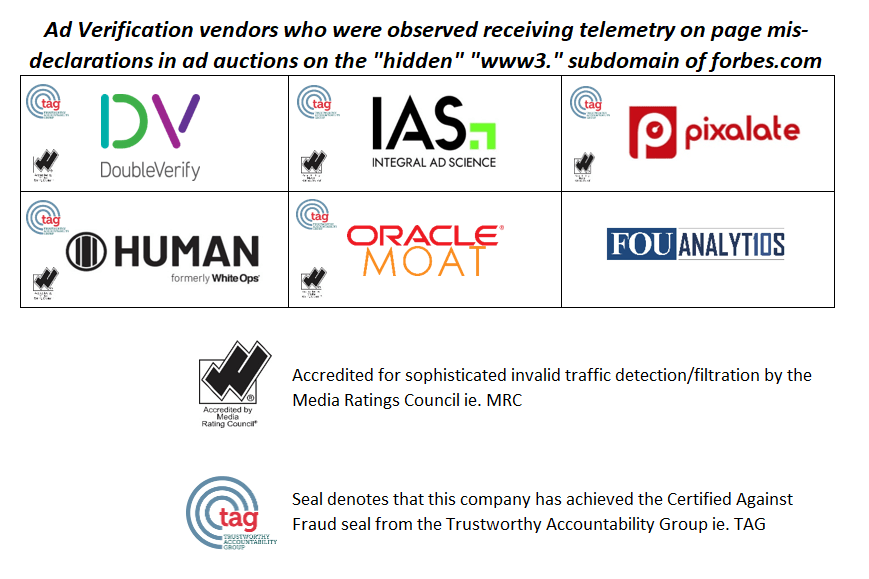

TAG-certified and MRC-accredited ad verification vendors such as Integral Ad Science, DoubleVerify, Oracle Moat, HUMAN (fka White Ops), and others were observed receiving telemetry that could have alerted them to sub-domain mis-declaration of the www3. subdomain inventory. Some of these same TAG and MRC accredited vendors allegedly did not notify media buyers of mis-declared ad inventory from Gannett Media (USA Today owner) 2021 and 2022.

Forbes appeared to have been operating and serving ads on the “Made for advertising” “www3.” sub-domain since at least May 3rd, 2017 (almost 7 years).

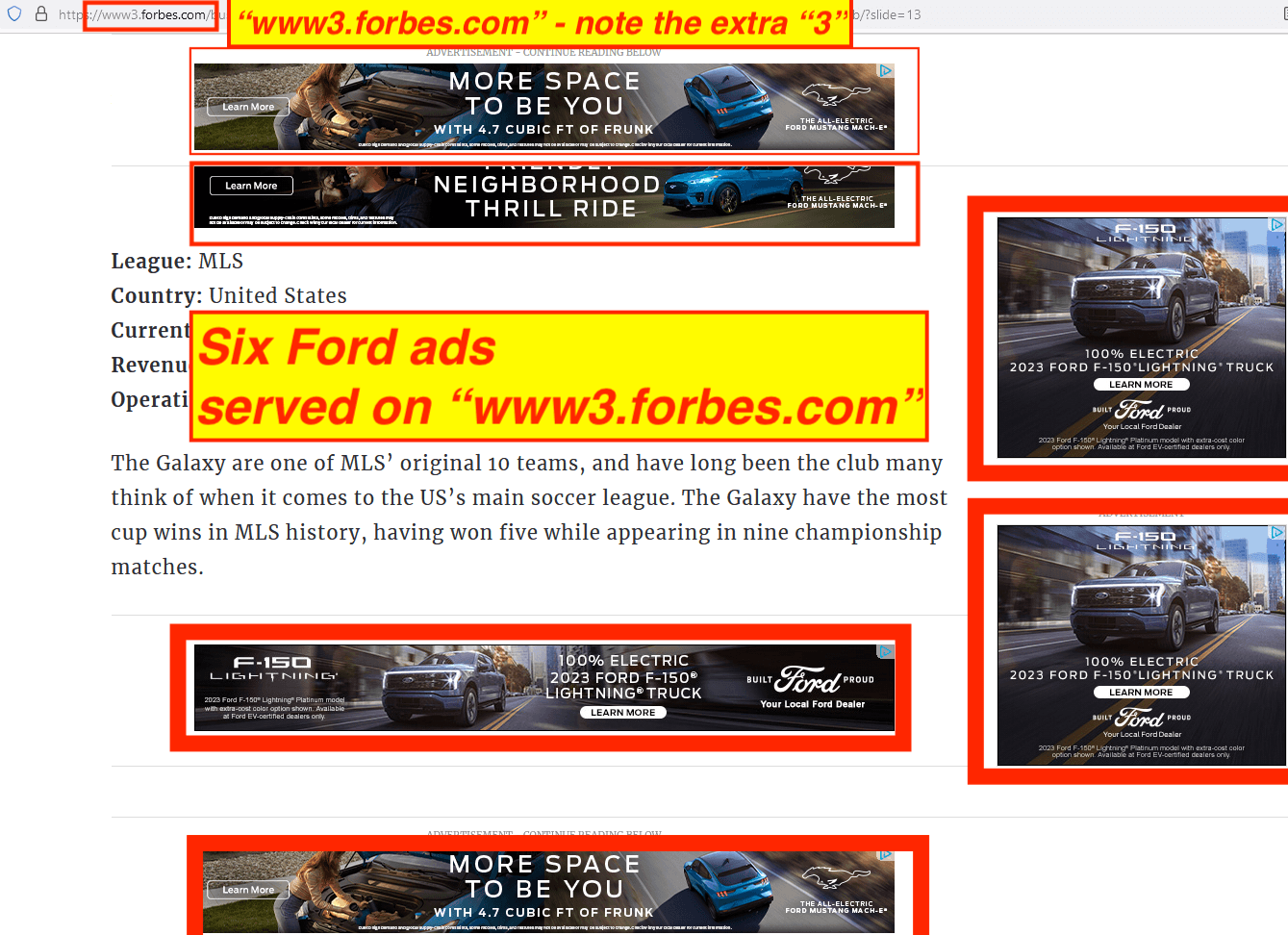

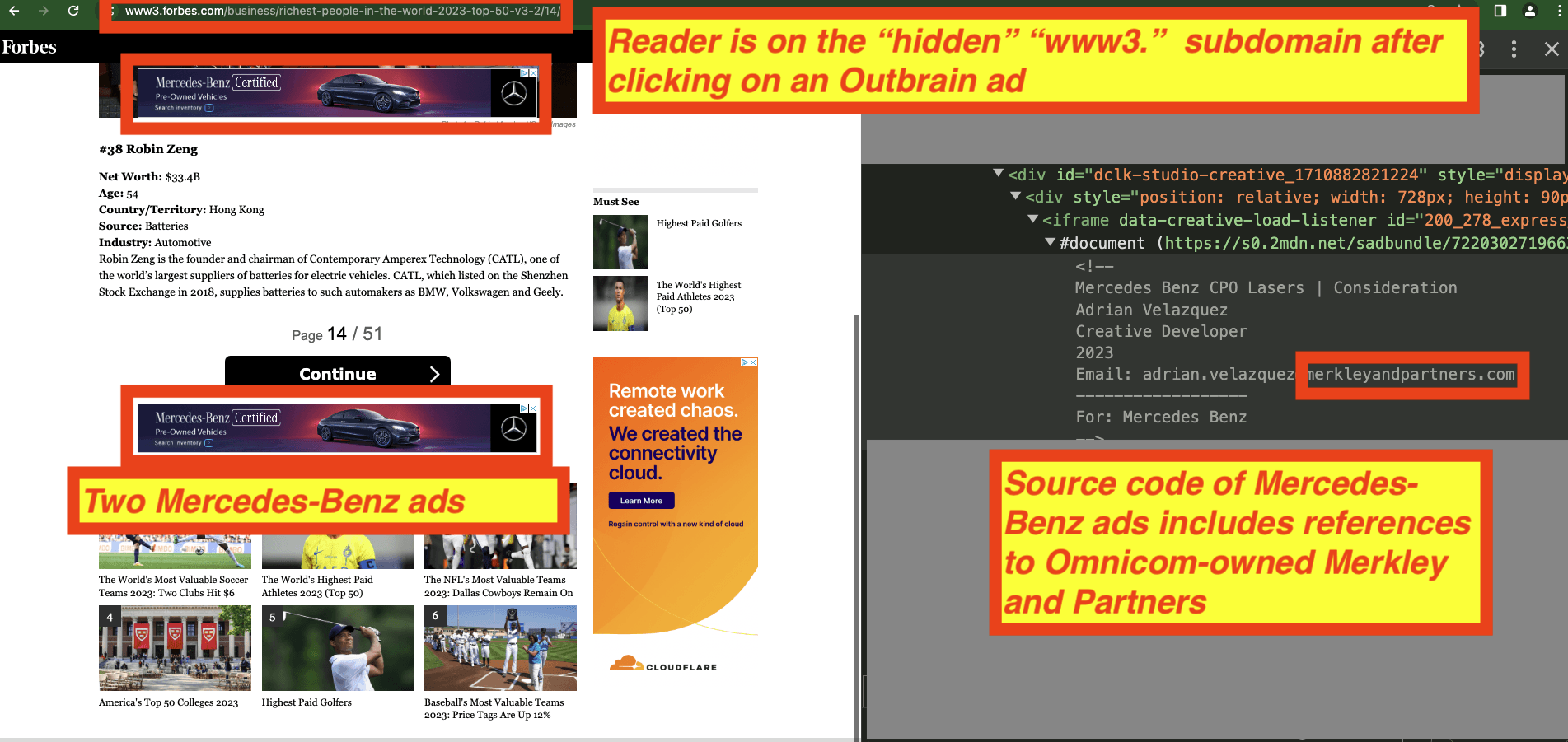

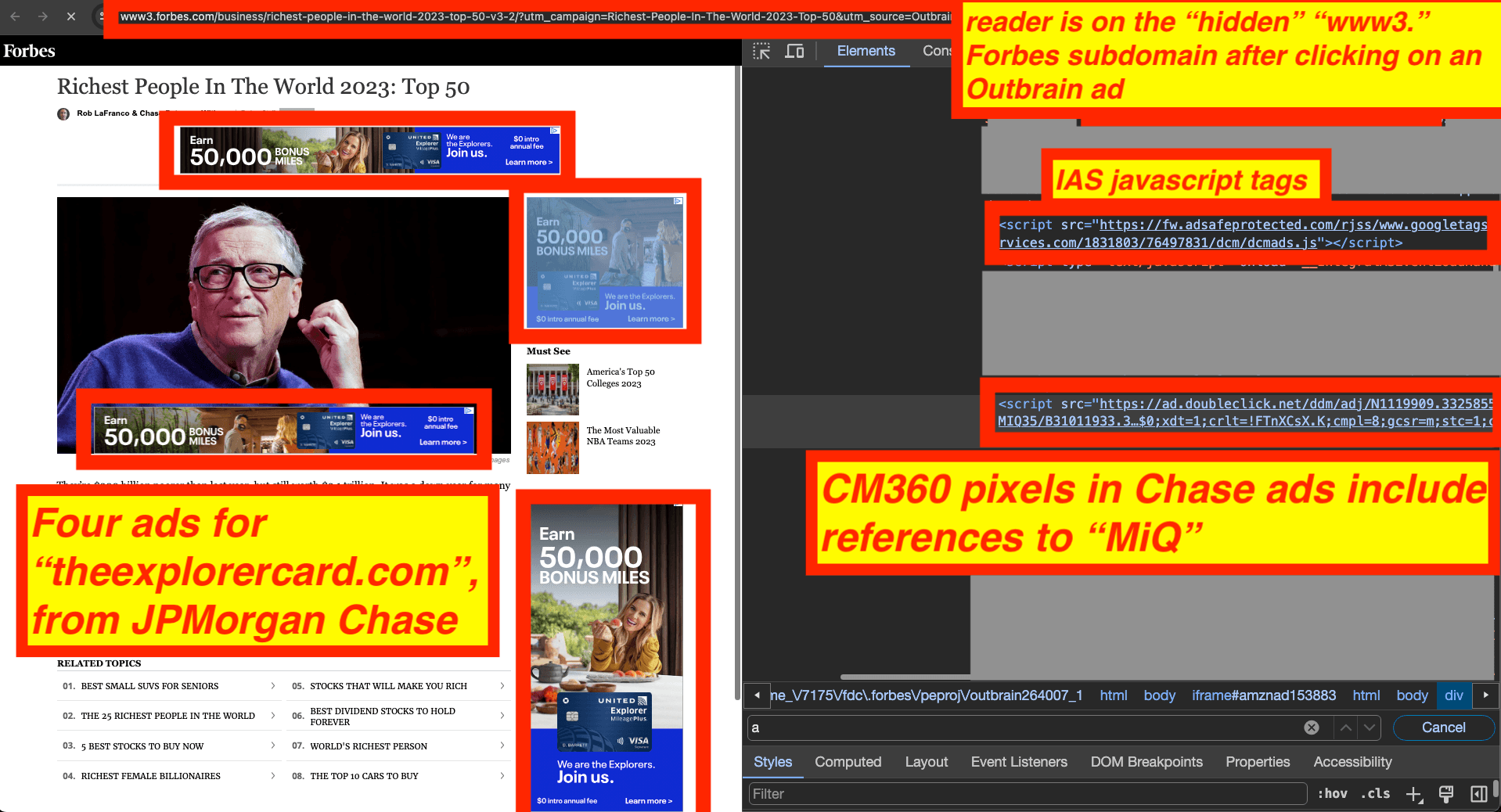

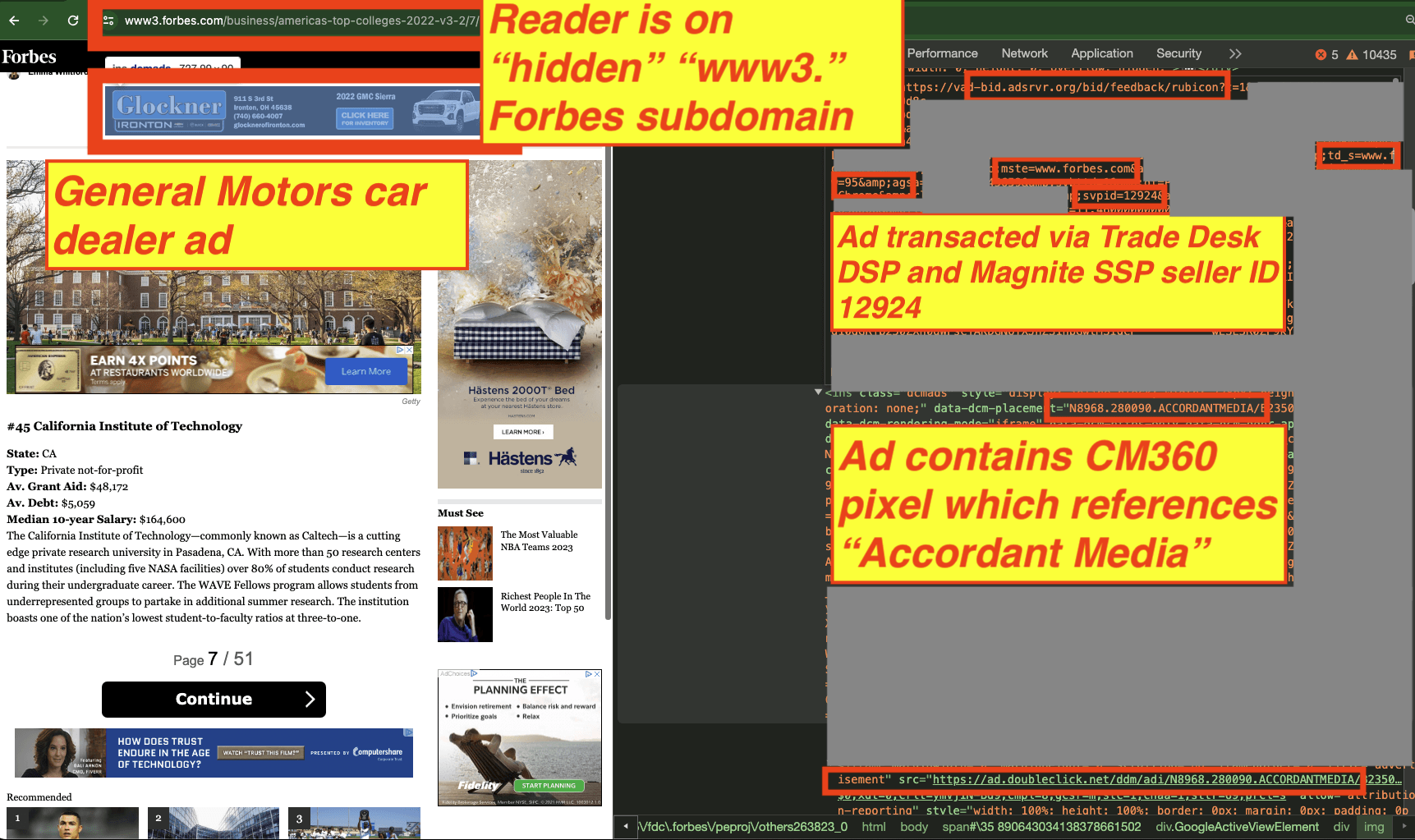

Hundreds of major brands were observed transacting ads on the “www3”. sub-domain. These include: JPMorgan Chase, Procter & Gamble, Publicis Sapient, Wall Street Journal, Ernst & Young (EY), Campaign (owned by Haymarket Media), Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), Cloudflare, Mercedes Benz USA, the New York Times, Freewheel Beeswax (owned by Comcast), General Motors, HSBC, Harley-Davidson, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), McDonald’s, TaxAct, Stout Risius Ross, Microsoft, Square, Brighthouse Financial, Maersk, General Electric, Fidelity, Marriott, Nationwide (insurance), ExxonMobil, Disney, USAA, Betterment, Schlage, Maserati, Oracle, E-Trade (part of Morgan Stanley), Honeywell, ZS Associates, Kroger, Saucony, Standard Chartered, H&R Block, Kimberly-Clark, Hertz (car rental), CubeSmart, FanDuel, Arcteryx, Fox News (Fox Nation), Standard & Poor (S&P) Global Market Intelligence, Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Ontario (Canada), State Street Global Advisors, Clorox, Invesco QQQ, Ford, L’Oreal, Safelite AutoGlass, Alcon, American Heart Association, BDO USA, AMC+, Ally, United Airlines, Vanguard, Planned Parenthood, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Texas Capital Bank, Chevron, Iowa Lakes Community College, Dior, Capital Bank, Deloitte, Walgreens, US Air Force, Unilever, Bayer, Citi, 5 Hour Energy, Growing Matters (American Seed Trade Association and National Pesticide Safety Education Center), Kenvue, JetBlue, Intuit, Shopify, Verizon, Volvo, and American Express were observed having their ads served on the “www3.” sub-domain. Several major media agencies, such as Dentsu, GIIR, Stagwell/Gale, Goodway Group, MiQ, Horizon Media, GroupM/WPP, Havas, Publicis Media, Omnicom, Interpublic Group (IPG), and Forward 3D Holdings.

One media buyer who reviewed an advanced copy of this report said:

| “Assuming I was okay with buying the MFA version of Forbes (which I'm not), I would certainly not pay the same CPM for these two drastically different ad experiences. By misdeclaring the URL, buyers are unknowingly overpaying and deserve refunds for anything that was incorrectly declared.” |

A marketing executive at a multinational Fortune 500 brand who reviewed an advanced copy of this study and their own log file data told Adalytics:

“I definitely am now questioning my comfort with placing ads on Forbes as this feels like domain spoofing that is not being captured by IAS. Example: I would never knowingly serve ads on any destination that can only be accessed via the chum bucket and are "hidden" from the true domain. This subdomain slideshow content isn't even accessible from the vanilla Forbes domain, which makes me think that Forbes themselves are embarrassed by the content. The fact that Forbes explicitly hides these MFA slideshow pages from Google and Bing search furthers that belief. We don't want to ever serve on MFA sites - but we especially don't want to serve on MFA sites that have degraded quality and for which the overall publisher is too embarrassed to link to from their top domain or surface the content in organic search results.” |

Table of Contents

Background - What are “Made for Advertising” or “Made for Arbitrage” sites? 20

DeepSee.io considers “www3.forbes.com” to be “Made for Advertising” 38

Forbes does not appear to have any subscriber paywall on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain 40

“Normal” forbes.com and “www3.forbes.com” appear to have different audience profiles 45

Results: Supply side platforms observed transacting ads on “www3.forbes.com” 59

Results: Demand side platforms and bidders observed transacting ads on “www3.forbes.com” 76

Results: potential direct sold insertion orders observed on “www3.forbes.com” 92

Results: agencies observed transacting ads on www3.forbes.com 100

Background - What are “Made for Advertising” or “Made for Arbitrage” sites?

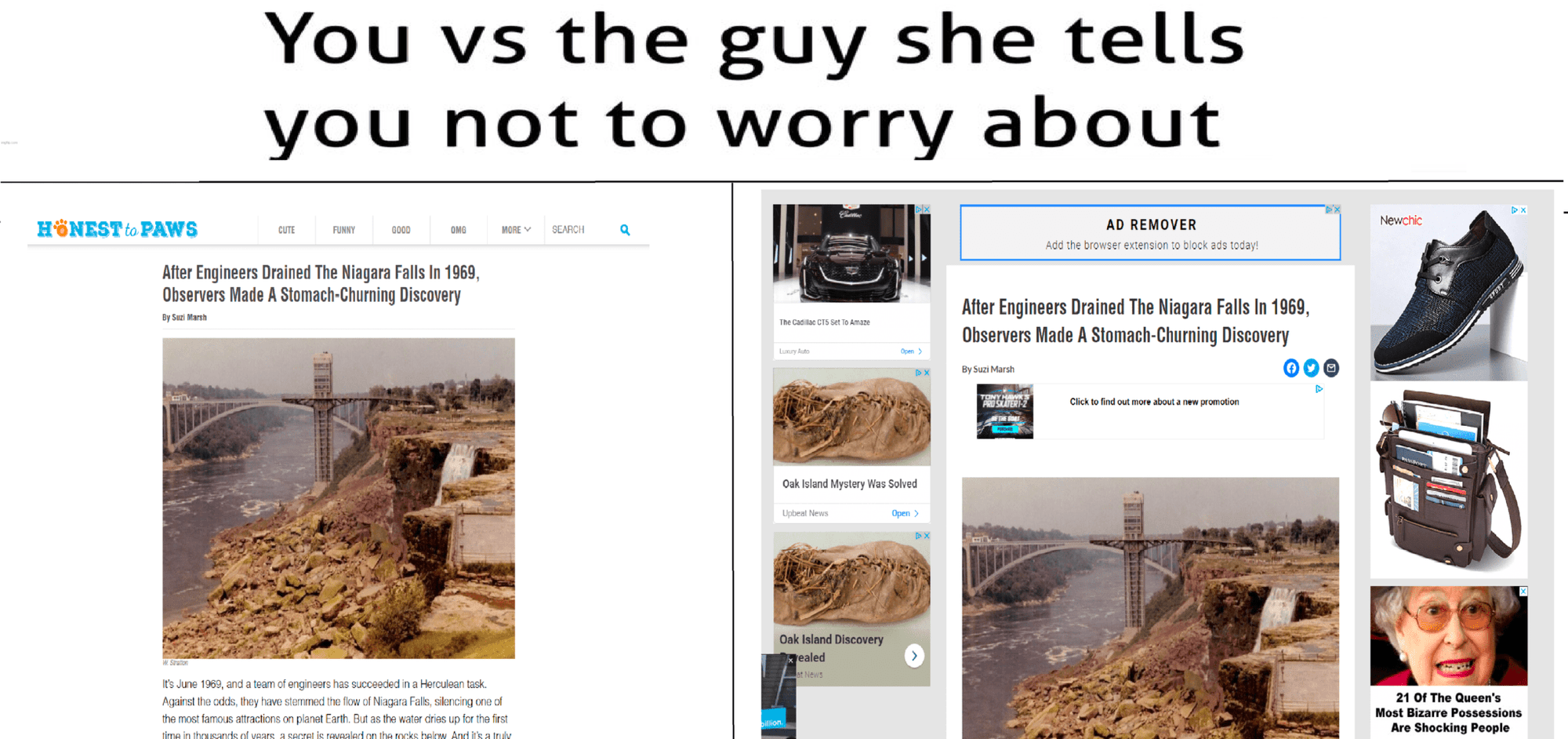

According to the Association of National Advertisers, “MFA sites typically use sensational headlines, clickbait, and provocative content to attract visitors and generate page views, which in turn generate ad revenue for the site owner. MFA sites also usually feature low-quality content, and may use tactics such as pop-up ads, auto-play videos, or intrusive ads to maximize ad revenue.”

Illustration of what a Made for Advertising (MFA) website can look like. Source: Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) UK

The ANA states: “Some of the lower quality websites, especially Made for Advertising sites, create more carbon emissions than the average site. That is because they have many ads per page and indiscriminately make ad calls to as many demand sources (like SSPs, DSPs, and ad networks) as they possibly can. According to Scope3 (a new industry organization with the mission to decarbonize advertising), MFA sites are 26 percent higher in carbon emissions than non-MFA inventory”.

Furthermore, the ANA states: “MFA sites generally are designed to fool digital advertising buyers. MFA websites exhibit high measurability rates, good viewability rates, and low

levels of invalid traffic, and usually have brand-safe environments. They also

perform higher on video completion rates, often with autoplay ads that have the

sound off. Notably, media CPMs paid on MFA websites are 25 percent lower than

those paid on non-MFA websites. All this makes MFA websites attractive to DSP

bidding algorithms. But typically, MFA websites don’t perform well on key metrics like brand lift. According to Jounce Media, ads on MFA websites are at least 50 percent less

likely to be attributed with driving a sale than the internet average.”

Furthemore, the ANA states: “The experience of visiting MFA websites can also fool digital advertising buyers. Going directly to an MFA site (i.e., simply typing in the URL of the site) results in a very different ad experience than clicking on a referral link (often at the bottom of the page on the site of a well-known publisher). In the former case, the user experience is generally cleaner. In the latter case it is not, typically exhibiting characteristics in the aforementioned definition such as high ad-to-content ratio and rapidly auto-refreshing ad placements. While investigating MFA supply, DeepSee.io found that many remove ads when people visit a site directly, but flood the page when people come via social media, search engines, or content recommendation widgets.”

The same site visited directly vs visited by paid link. Source: DeepSee.io

Two screenshots of the same website. The top screenshot shows when the site is visited directly. The bottom screenshot shows there is significantly more ad density on the page when the visit is visited by a paid ad click on another website (Taboola, Outbrain, Facebook, etc).

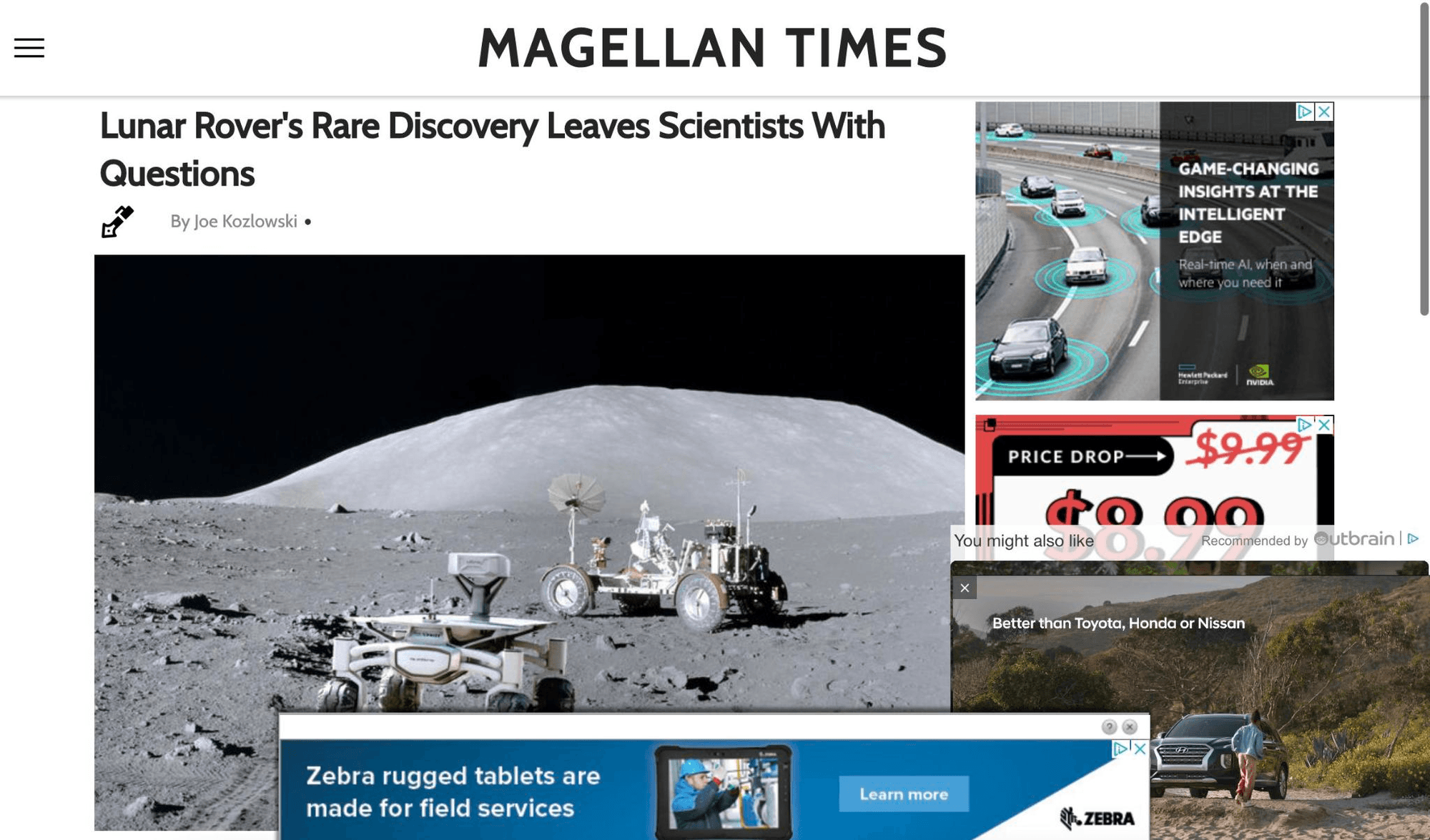

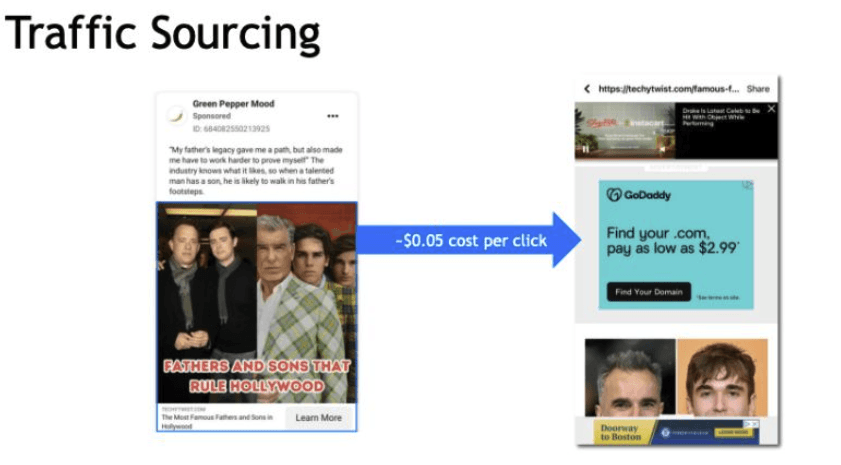

The ANA states that Made for Advertising websites have “High percentage of paid traffic sourcing” and “often have little-to-no organic audience and are instead highly dependent on visits sourced from clickbait ads that run on social networks, content recommendations platforms, and even on the websites of reputable publishers. Buying paid traffic is the primary cost driver of operating an MFA business. Overcoming paid traffic acquisition costs requires MFA publishers to engage in aggressive monetization practices and arbitrage.”

Some MFA sites go even a step further, and specifically configure their websites to not appear in organic Google or Bing search results. This further reduces the probability that a viewer would arrive at one of the websites through organic, un-paid traffic sources.

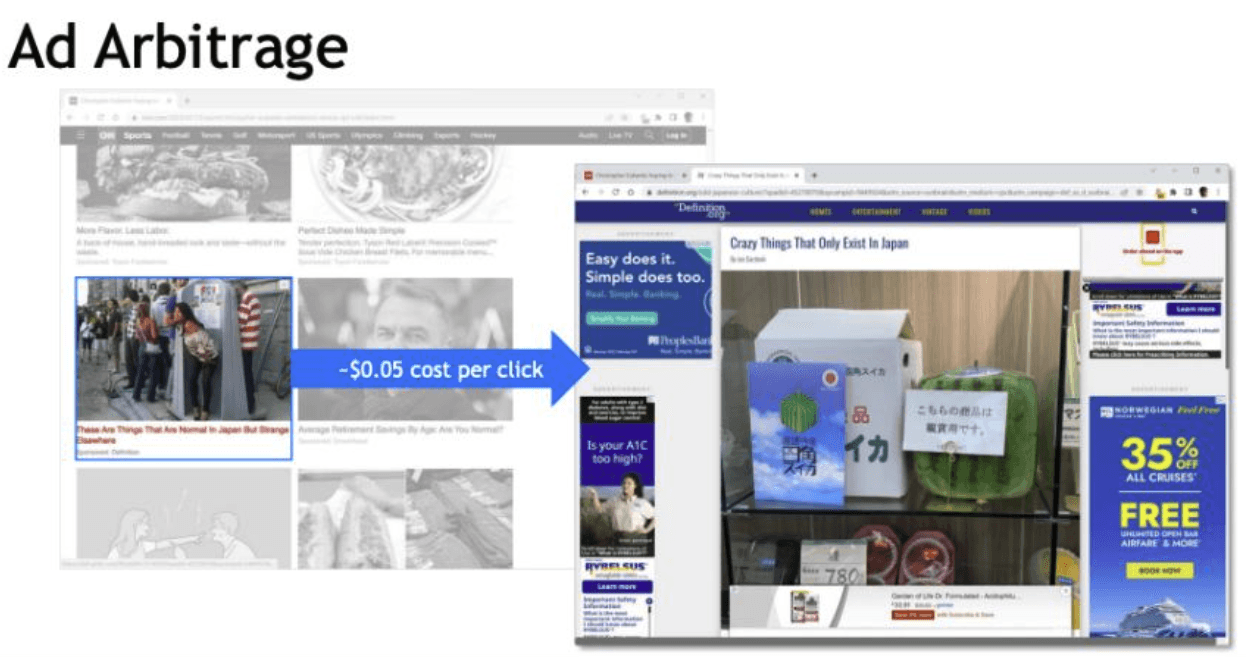

“MFA sites, also referred to by the 4A’s as “Made for Arbitrage” sites, are created for that singular purpose—to simultaneously buy and sell advertising inventory.” The ANA said “MFA sites generally are designed to fool digital advertising buyers. MFA websites exhibit high measurability rates, good viewability rates, low levels of invalid traffic, and usually have brand-safe environments.”

Source: Jounce Media, via Campaign

Source: Jounce Media, via Campaign

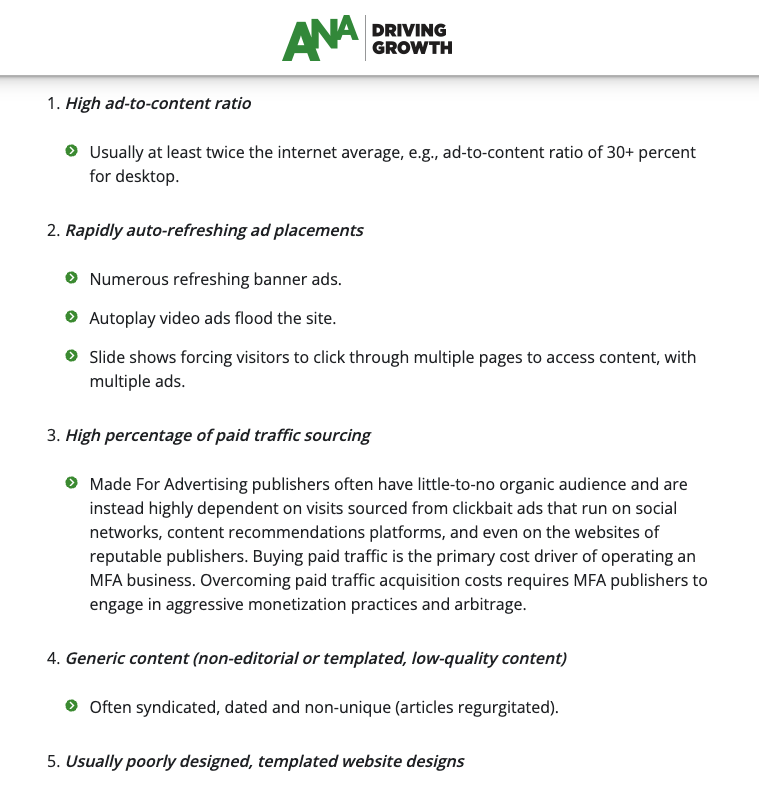

The trade organizations said MFA sites usually exhibit some combination of the following characteristics:

High ad-to-content ratio

Usually at least twice the internet average, e.g., ad-to-content ratio of 30+ percent for desktop.

Rapidly auto-refreshing ad placements

Numerous refreshing banner ads.

Autoplay video ads flood the site.

Slide shows forcing visitors to click through multiple pages to access content, with multiple ads.

High percentage of paid traffic sourcing

Made For Advertising publishers often have little-to-no organic audience and are instead highly dependent on visits sourced from clickbait ads that run on social networks, content recommendations platforms, and even on the websites of reputable publishers. Buying paid traffic is the primary cost driver of operating an MFA business. Overcoming paid traffic acquisition costs requires MFA publishers to engage in aggressive monetization practices and arbitrage.

Generic content (non-editorial or templated, low-quality content)

Often syndicated, dated and non-unique (articles regurgitated).

Usually poorly designed, templated website designs

A consortium of leading advertising trade groups established a joint definition for “Made for Advertising” sites. Source: Association of National Advertisers

Lastly, the IAB UK published a “Guide to identify made for advertising websites” in July 2023.

The “www3.” subdomain of forbes.com was observed engaging in practices consistent with the definition of “Made for Advertising” or “Made for Arbitrage”

The “www3.” subdomain of forbes.com was observed engaging in several practices that are consistent with the ANA’s, WFA’s, ISBA’s, 4A’s, Jounce Media’s, and DeepSee.io’s definition of “Made for Advertising” (or “Made for Arbitrage”) websites.

Specifically, the “www3.” subdomain of forbes.com appears to:

source ~70+% of its audience from paid display ads on other websites, served through Taboola and Outbrain “chumbox” ads

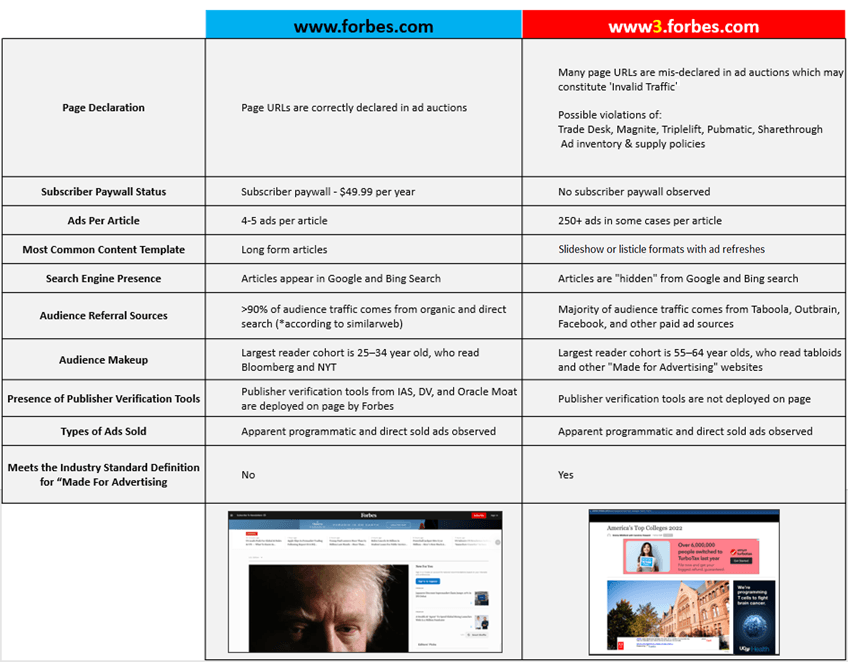

serve content in either listicle format or carousel slides, with significant numbers of ad refreshes that can result in a consumer seeing more than 200+ ad impressions in a few minutes of browsing the “www3.” subdomain. One ad tech professional asserted: “The extra long sequence of low content slides in slideshows is also a classic MFA indicator.”

have high ad to content ratio, wherein sometimes five ads are served adjacent to a Getty Images-sourced picture with several lines of text

use templated page structures, which include: large numbers of images from free sources such as Getty Images, served with a subtitle and several lines of text. Each www3 subdomain article appears to be some form of a list, such as “Highest Paid Golfers”, “America’s Top 50 Colleges 2023”, or “Richest People In The World 2023: Top 50”

specifically instruct Google and Bing’s crawlers not to index the articles on the “www3” subdomain, which prevents those pages or articles being found through organic searches on either Google or Bing

automatically redirect users who try to open www3.forbes.com to www.forbes.com, preventing the user from reviewing the content on the www3. subdomain unless they know an exact page URL or first click on an Outbrain ad on another website that redirects them to the www3 subdomain.

whereas the “normal” “www.forbes.com” domain appears to deploy publisher adtech solutions from verification vendors such as IAS, Oracle Moat, and DoubleVerify, the ad verification vendors’ publisher tools appear not to have been deployed or configured by Forbes on the “www3.” subdomain. This would reduce the data and telemetry that the verification vendors receive for page view sessions on the “www3.” subdomain

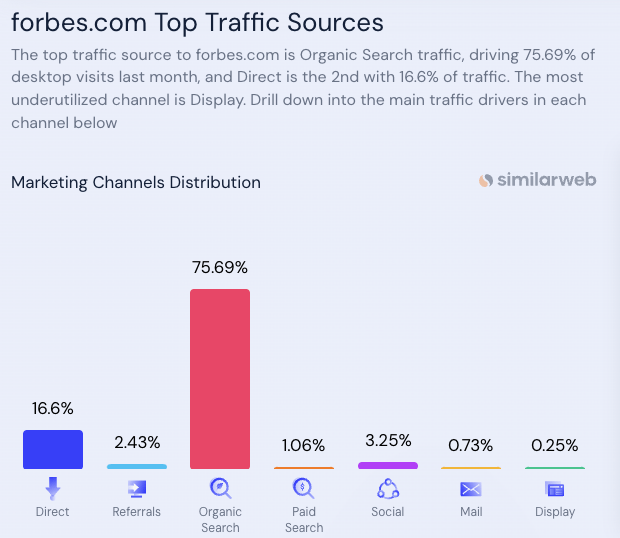

Firstly, if one considers the audience traffic sourcing for forbes.com versus the www3.forbes.com subdomain, one will note a large difference in how each online property sources its readership. The main “forbes.com” domain sources 90+% of its readership through organic search or direct page navigation according to Similarweb.

Top traffic sources to forbes.com, according to Similarweb. Forbes.com sources over ninety percent of its audience traffic from either organic search or from direct navigation.

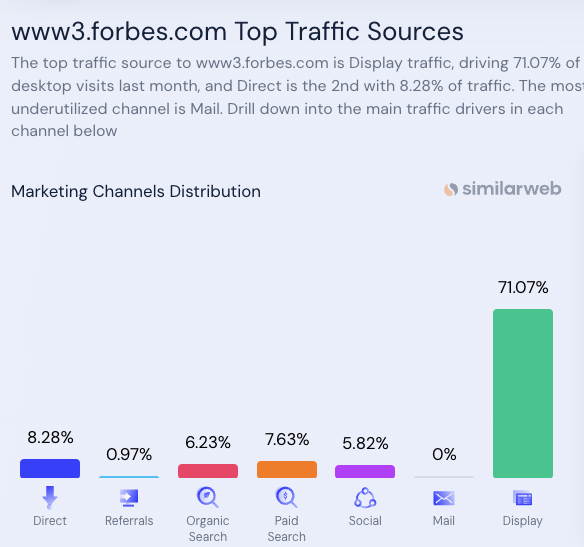

However, the “www3.” subdomain sources more than 70% of its readership through paid display ads running on other websites.

Top traffic sources to www3.forbes.com, according to Similarweb. www3.forbes.com sources over seventy percent of its audience traffic from paid display ads.

One can observe this paid traffic sourcing strategy by visiting other websites - such as foxnews.com, and locating Outbrain ads directing the viewer to the www3.forbes.com subdomain (rather than the ‘normal’ www.forbes.com domain).

Screenshot showing an Outbrain ad on foxnews.com. If a reader clicks on the ad, they get redirected (via “paid.outbrain.com/network/redir”) to a specific slideshow article on www3.forbes.com titled: “America’s Top Colleges 2022”: https://www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3/?utm_campaign=Americas-Top-Colleges-2022-Forbes&utm_source=Outbrain&utm_term=Fox+News

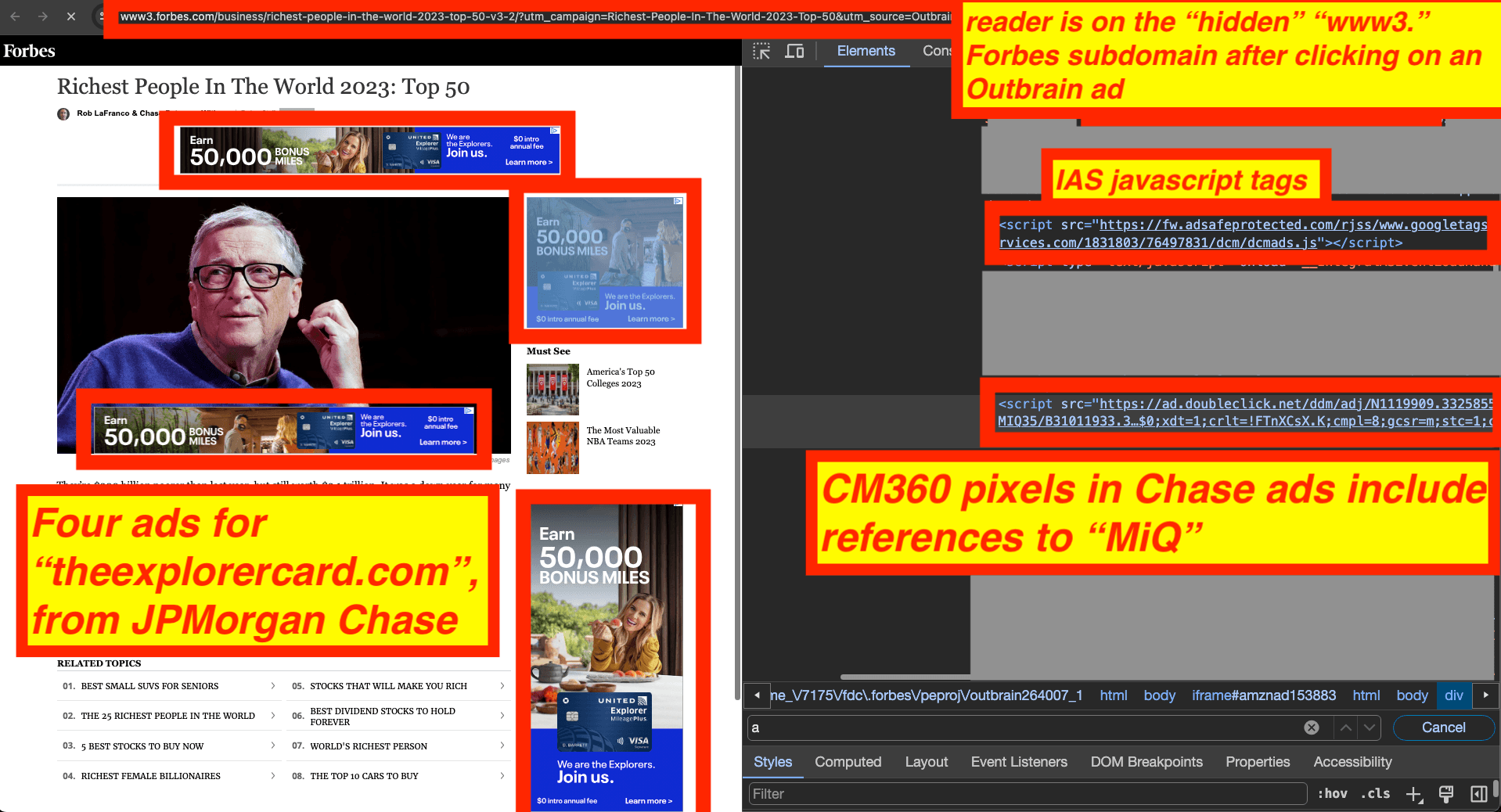

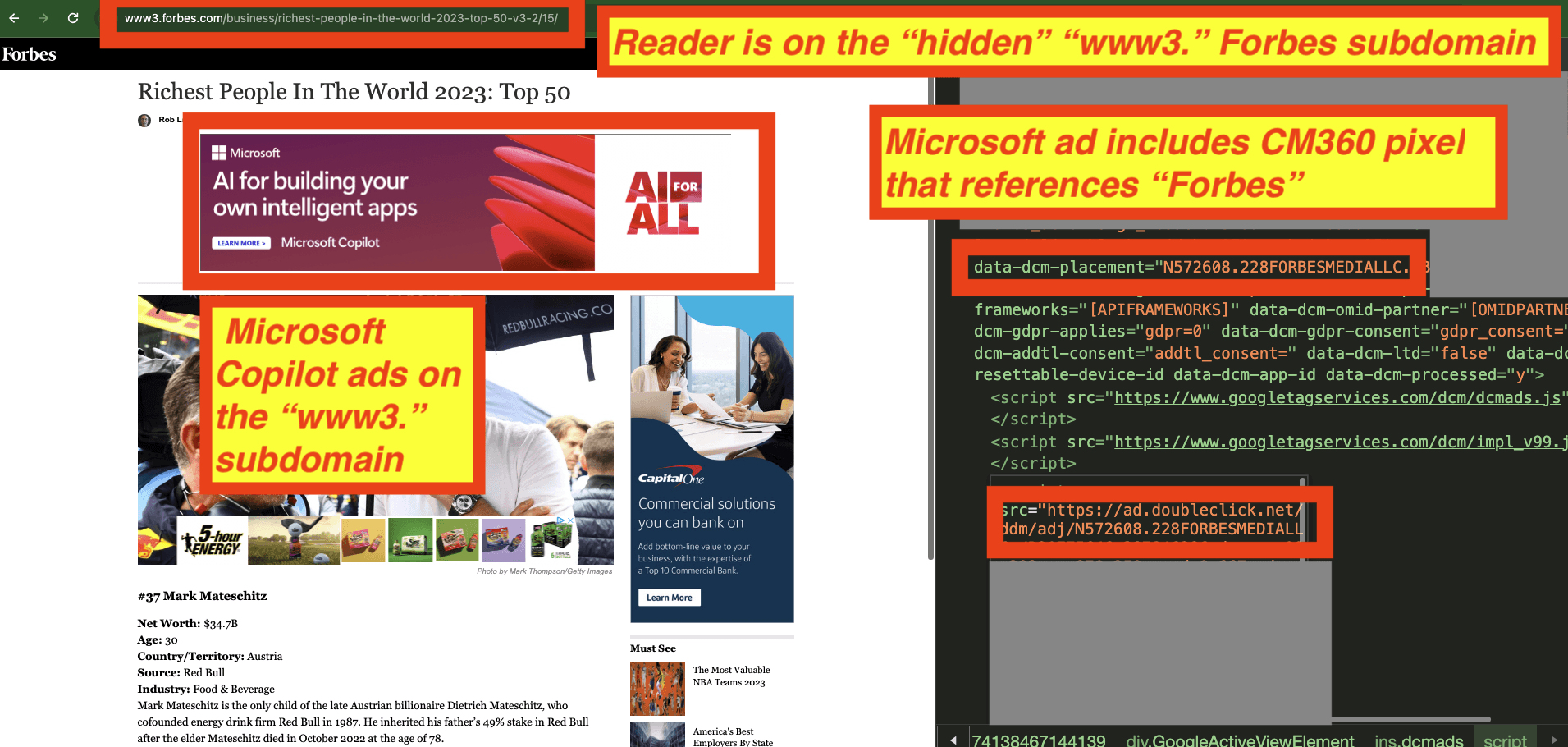

Screenshot showing an Outbrain ad on foxnews.com. If a readers clicks on the ad, they get re-directed to a specific slideshow article on www3.forbes.com subdomain titled: “Richest People In The World 2023: Top 50” - https://www3.forbes.com/business/richest-people-in-the-world-2023-top-50-v3-2/?utm_campaign=Richest-People-In-The-World-2023-Top-50&utm_source=Outbrain&utm_medium=ob264007d0us209082301&lcid=ob264007d0us209082301&utm_content=006a55f6e2a4ca1b414574e6c01c9c048d&utm_term=Fox+News

One will note that, while Forbes appears to run ads to attract readers to these “www3.” subdomain articles, it is simultaneously instructing Google and Bing’s crawlers not to index the pages on the “www3.” subdomain and avoid making those specific pages via search engine results visible.

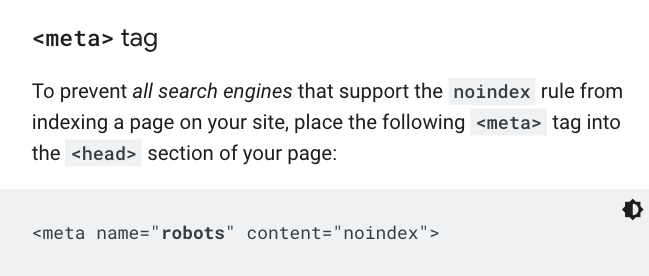

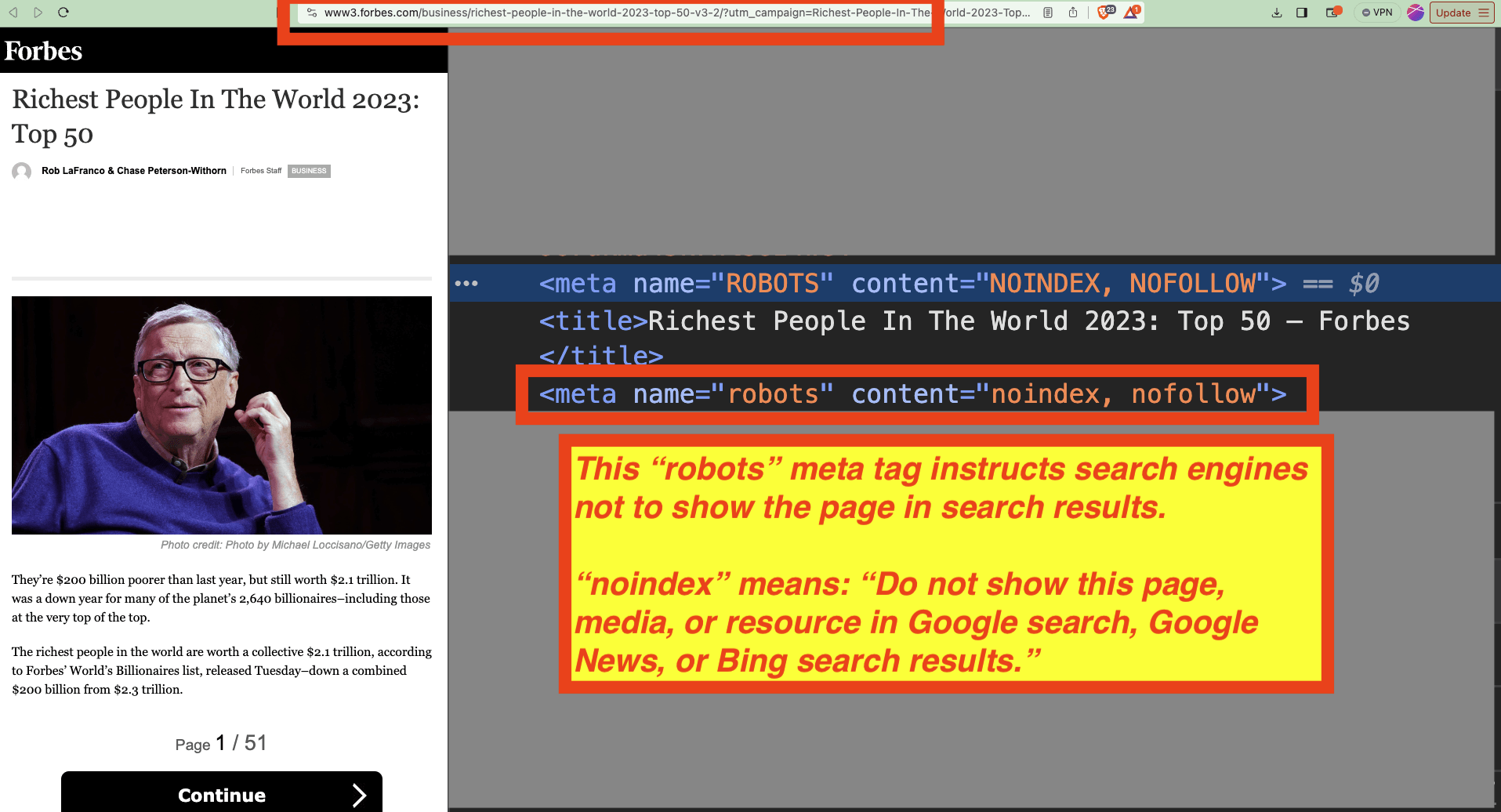

Wikipedia and Google’s documentation titled: “Block Search indexing with noindex” explain that the “noindex” attribute for the “robots” meta tag prevents all searching engines from indexing a specific page on your site.

Source: Google’s documentation titled: “Block Search indexing with noindex”

Articles on the “www3.” Forbes subdomain are observed to consistently make use of the “noindex” robots meta tag.

Screenshot of an article on the “www3.forbes.com” subdomain, titled: “America’s Top Colleges 2022”. The source code of the page shows the “noindex” “robots” meta tag.

Screenshot of an article on the “www3.forbes.com” subdomain, titled: “Richest People In The World 2023: Top 50”. The source code of the page shows the “noindex” “robots” meta tag.

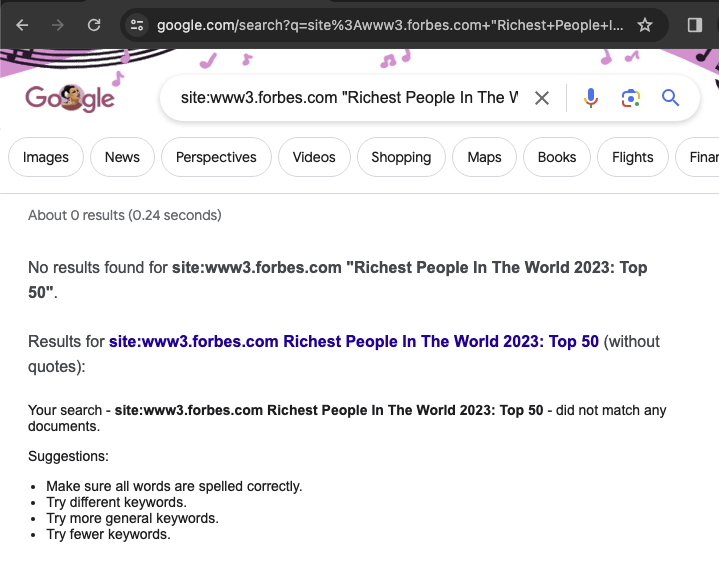

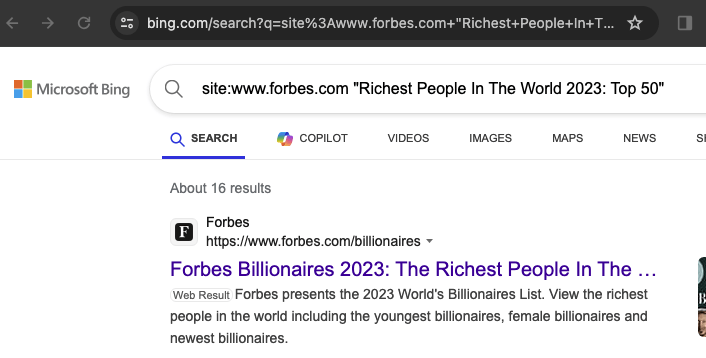

These specific articles on the “www3.” subdomain cannot be found via Bing or Google search results. However, searching for the same article titles yields search results pointing to the “normal” “www.forbes.com” subdomain.

Screenshot of Google search showing no search results when one searches for a specific page on www3.forbes.com. This is due to the “noindex” attribute configured on those specific pages.

Screenshot of Google search showing no search results when one searches for a specific page on www3.forbes.com. This is due to the “noindex” attribute configured on those specific pages.

Screenshot of Bing search showing no search results when one searches for a specific page on www3.forbes.com. This is due to the “noindex” attribute configured on those specific pages.

If one searches for the exact same article titles but on the “normal” “www.forbes.com” subdomain, one does indeed find search results. All the search engine page results point to the regular “www.forbes.com” subdomain, not the MFA “www3.forbes.com” subdomain.

Screenshot of Google search showing search results when one searches for a specific page on the “normal” www.forbes.com website. There is no “noindex” attribute configured on those specific pages.

Screenshot of Bing search showing search results when one searches for a specific page on the “normal” www.forbes.com website. There is no “noindex” attribute configured on those specific pages.

The ad layout, density, and refresh behavior on “www3.forbes.com” appears to be very different from what a reader (or digital media planner at an agency) might find when they visit the “normal “www.forbes.com”.

One consumer who visited the “www3.” forbes subdomain was served 27 New York Times subscription ads and 201+ ads total while viewing a 52 slide slideshow on the “www3.” Forbes subdomain titled: “Richest People In The World 2023: Top 50”. The New York Times paid an effective cumulative CPM of $60.39 to serve ads to that one consumer.

DeepSee.io considers “www3.forbes.com” to be “Made for Advertising”

Adalytics reached out to Rocky Moss, the CEO of DeepSee.io. DeepSee.io is a leading digital publisher intelligence provider, which has published much of the industry thought leadership on “Made for Advertising”. DeepSee.io helped define “Made for Advertising” for the Association of National Advertisers (ANA), the 4A’s, the World Federation of Advertisers (WFA) and the Incorporated Society of British Advertisers (ISBA). DeepSee.io was deeply involved in the ANA’s 2023 Programmatic Media Supply Chain Transparency Study.

DeepSee.io was asked if “www3.forbes.com” meets the conditions to be considered “Made for Advertising”. The following is from a written Q&A with Rocky Moss:

Q: Is www3.forbes.com considered MFA?

A: “www3.forbes.com meets DeepSee.io's (and the ANA/4As) Made-for-Advertising (MFA) criteria based on its ~100% paid traffic rate, and its non-unique content. Furthermore, www3 articles are slideshow format, and introduce extra ad-units into the article images themselves, creating a much higher frequency & density of advertisements compared to articles hosted on the root domain.”

Q: What is meant by non-unique content?

A: “Typically, MFA sites all publish articles coming from a shared content library. The syndication is not a secret; many MFA articles start with a "this article originally appeared on _____.com" type of message. In the case of www3.forbes.com, the content is pieced together from previously written staff-writer / contributor content (some with attribution, some loosely attributed to "Forbes").

For example:

https://www3.forbes.com/business/the-net-worth-of-2024-presidential-candidates-v3/2/ - Attributed to "Forbes"

Content in that slide is word-for-word lifted from:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/jemimadenham/2023/12/01/why-cornel-west-is-broke/

&

https://www.forbes.com/sites/zacheverson/2023/12/01/checks--imbalances-why-cornel-west-is-broke

It's the same for every slide, and pretty much any article; generally speaking, it's super easy to plug a whole sentence from the www3 articles into google and find where it was originally published.”

Q: Is forbes.com as a whole considered MFA?

A: “We added this subdomain (but NOT the root domain) to our MFA list in March of 2023. This is normal practice, as we don't want to limit an advertiser's ability to support the non-arbitrage inventory from a given site. We'd only flag the domain as a whole if the MFA subdomain activity represented the majority of all visits to the property.”

Q: Describe any issues you've encountered around blocking this subdomain:

A: “This year, we were able to collaborate with Adalytics in support of a mutual buyer client. We provided the MFA list in its entirety for pre-bid blocking purposes (with www3.forbes.com on it), but you (Adalytics) noticed a frustrating pattern: our client somehow purchased inventory which was labeled "www.forbes.com," but the measurement tag was able to determine the true source of inventory was "www3.forbes.com."

The primary explanation for that is domain spoofing. As to why it wasn't flagged as spoofing: an IVT vendor could easily miss that if they consider all inventory under a root domain to be interchangeable, but the fact is that it's not. To get it right, an IVT measurement firm would have to be aware of which subdomains should be treated as distinct from the root domain, but it's clear that is not happening.”

Forbes does not appear to have any subscriber paywall on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain

Forbes does not seem to deploy its subscriber paywalls on the “www3.” subdomain, unlike on the regular Forbes website.

Forbes appears to create different ad slots on the “www3.” subdomain, and name them after vendors such as “Taboola” or “Outbrain”

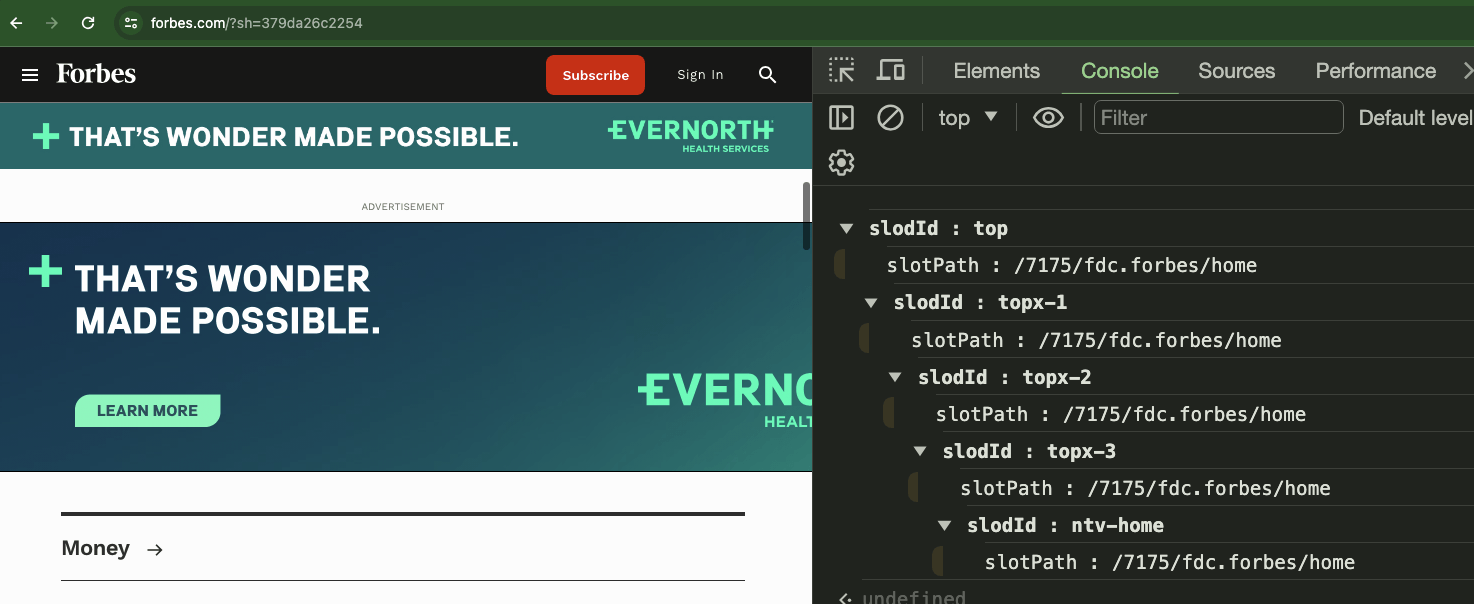

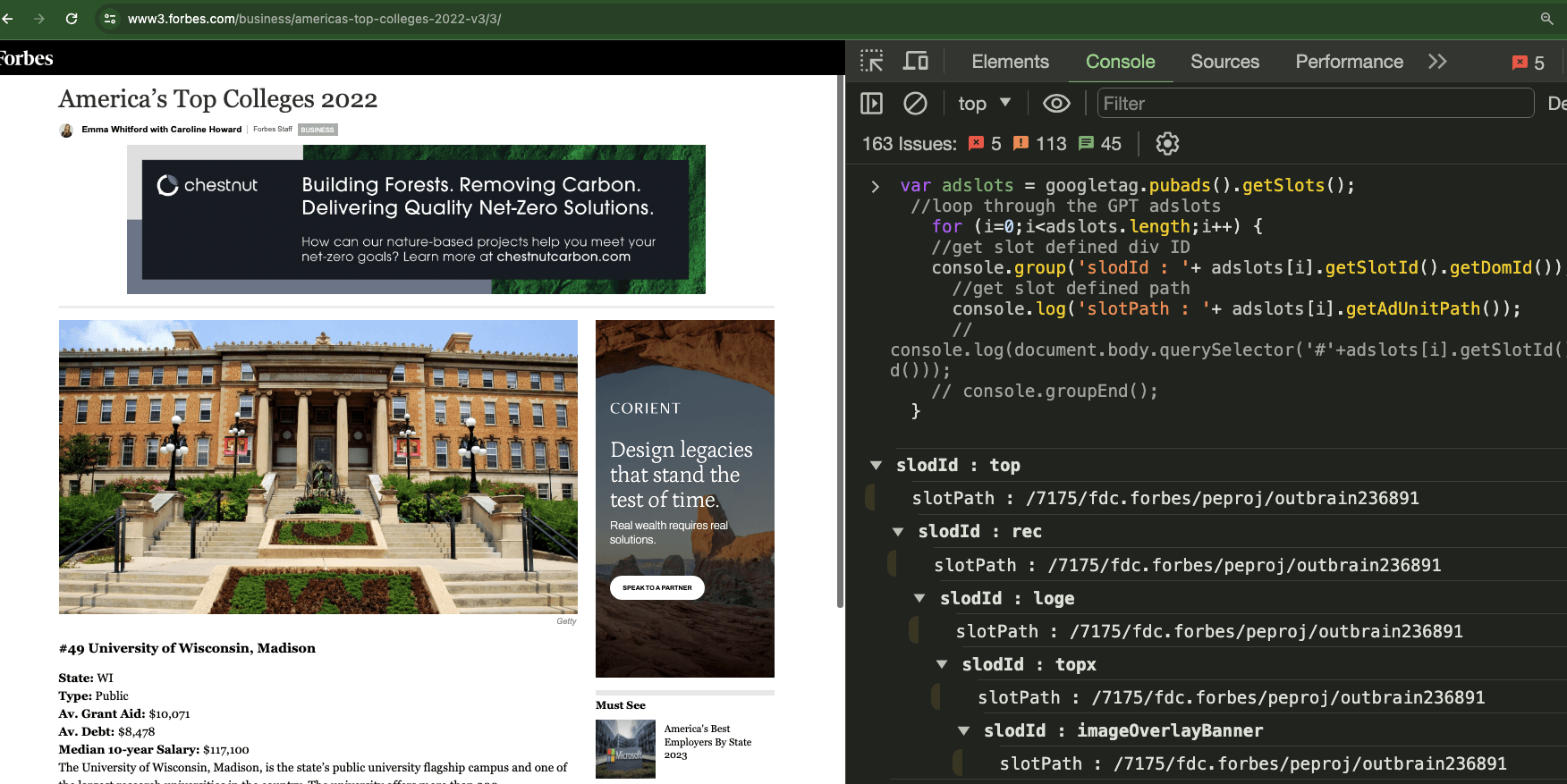

There appears to be a notable difference in the naming conventions Forbes uses to label ad slots on the “normal” “www.forbes.com” website and the “hidden” “www3.forbes.com” subdomain.

The first two screenshots below illustrate that all the ad slots on forbes.com include the string “fdc.forbes/home” or “fdc.forbes/article/premium”.

The first two screenshots below illustrate that all the ad slots on forbes.com include the string “fdc.forbes/home” or “fdc.forbes/article/premium”.

However, the screenshot below on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain shows that all the ad slots on this particular page end with the string “fdc.forbes/peproj/outbrain236891”. It is unclear why Forbes chose to include a reference to Outbrain in the name of the ad slots. Other ad slots on the “www3.” subdomain were observed to include references to “taboola” and “adwords”.

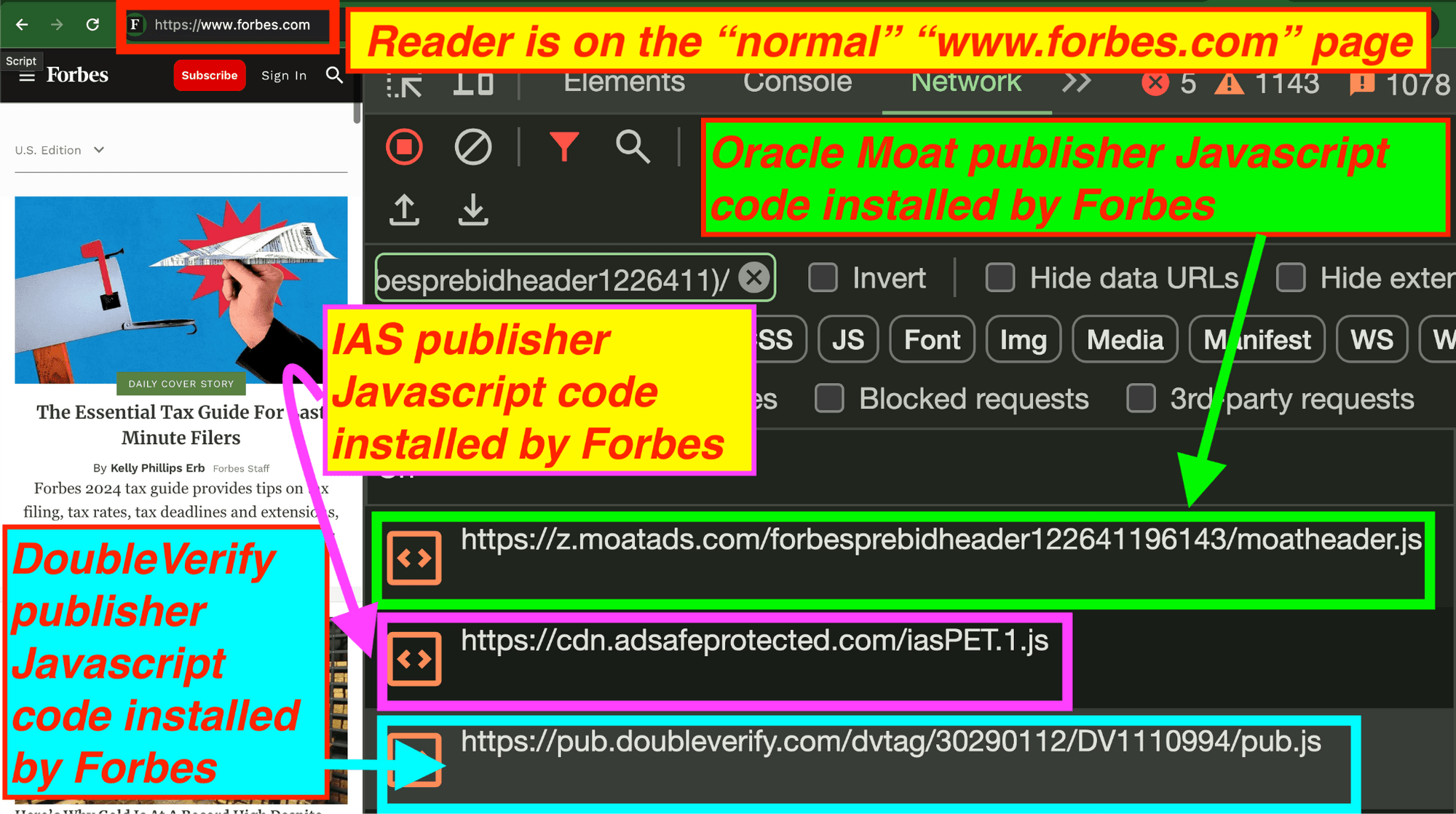

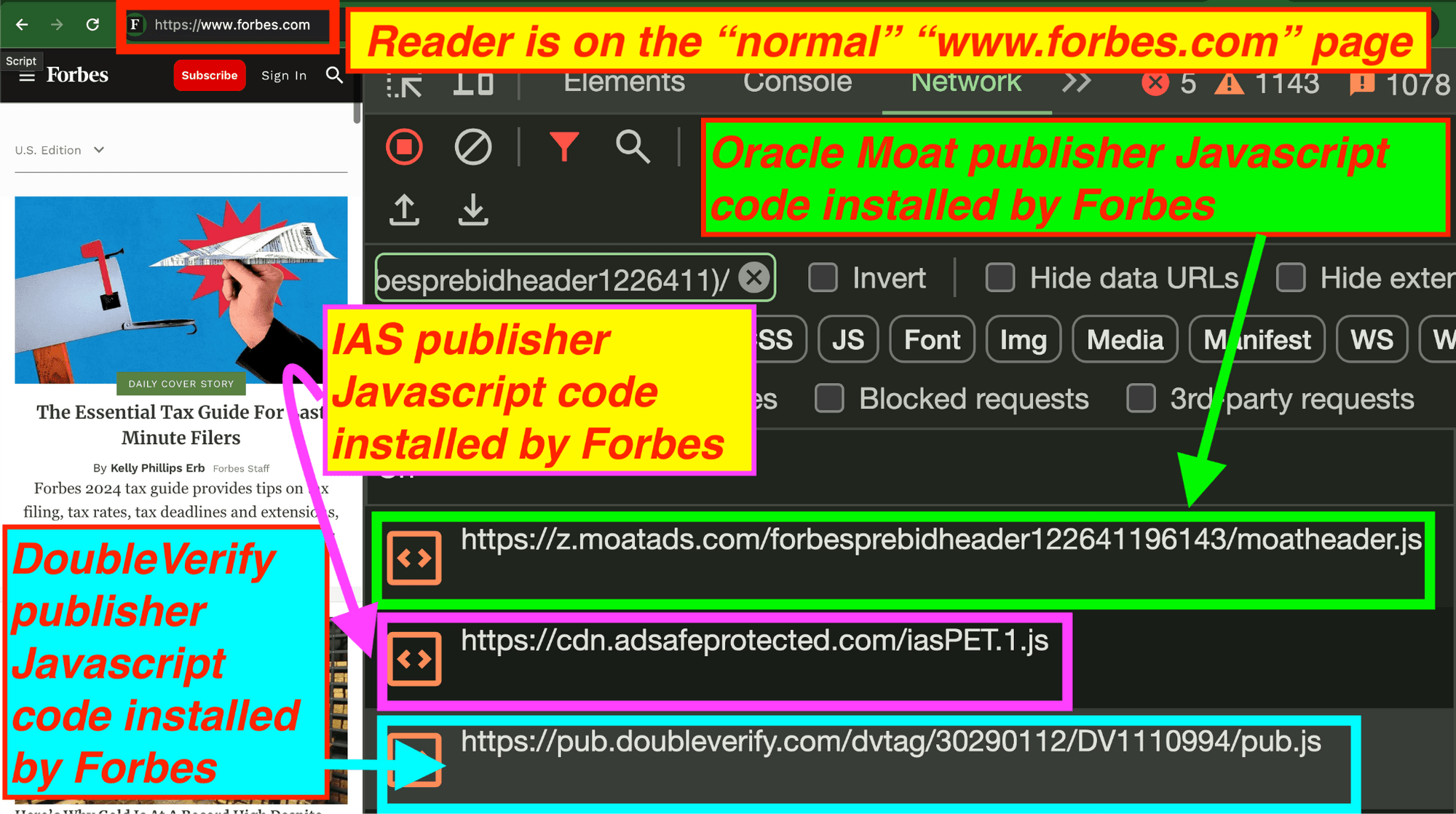

Forbes does not appear to deploy publisher ad verification tools on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain

Whereas the “normal” “www.forbes.com” domain appears to deploy publisher adtech solutions from verification vendors such as IAS, Oracle Moat, and DoubleVerify, the ad verification vendors’ publisher tools appear not to have been deployed or configured by Forbes on the “www3.” subdomain. This would reduce the data and telemetry that the verification vendors receive for page view sessions on the “www3.” subdomain.

In the screenshot below, one can observe Chrome Developer Tools’ “Network” tab opened on the “normal” “www.forbes.com” website. The “Network” tab shows that the “normal” “www.forbes.com” website loads publisher Javascript code from three ad verification vendors:

Oracle Moat - https://z.moatads.com/forbesprebidheader122641196143/moatheader.js

IAS - https://cdn.adsafeprotected.com/iasPET.1.js

DoubleVerify - https://pub.doubleverify.com/dvtag/30290112/DV1110994/pub.js

To be clear, this is code that is loaded directly from the main page frame and Document Object Model (DOM) of “www.forbes.com”; the code is not being loaded or initiated from within an ad iframe. These are apparently the publisher suite Javascript tools of the verification vendors; and should not be confused with the advertiser (“buy side”) ad verification tools provided to media buyers. The advertiser Javascript code loads within ad iframes.

However, if a reader clicks on an Outbrain ad and is redirected to “hidden” “www3.forbes.com” subdomain, it appears that Forbes does not configure or deploy the publisher-specific ad tools from Oracle Moat, IAS, or DoubleVerify on the “www3.” subdomain. The screenshot below shows that none of the aforementioned Javascript files or endpoints is invoked when ads are being served to a consumer on the “www3.” subdomain.

It is unclear why Forbes does not appear to deploy the publisher-side Javascript tools of these three vendors on the “www3.” subdomain. However, the consequence of this is that the ad verification vendors would receive less data and telemetry about the ad serving and media environment on the “www3.” subdomain, which could theoretically bias their calculations of metrics such as “ad clutter” or ad density on Forbes.

“Normal” forbes.com and “www3.forbes.com” appear to have different audience profiles

Data from website traffic analytics firm Similarweb shows that the largest age group of visitors on the “normal” “www.forbes.com” domain are “25-34 year olds”. However, Similarweb shows that the largest age group of visitors on the “hidden” “www3.forbes.com” subdomain are “55-64 year olds”.

Data from Similarweb shows that the largest age group of visitors on the “normal” “www.forbes.com” domain are “25-34 year olds”.

Data from Similarweb shows that the largest age group of visitors on the “hidden” “www3.forbes.com” subdomain are “55-64 year olds”.

Data from Similarweb show large differences in behavior amongst the audiences of the “normal” forbes.com and the “hidden” “www3.forbes.com” subdomain. Similarweb shows the “audience targeting”, “affinity”, and “browsing interests” of the readers of the “normal” “www.forbes.com” website are predominantly other business and news websites, such as businessinsider.com, nytimes.com, and bloomberg.com. However, Similarweb shows that the browsing interests of visitors to the “hidden” “www3.forbes.com” subdomain include tabloid or other “Made for Advertising” websites.

Some page data submitted to ad auctions on the “www3.” Forbes subdomain appears to be mis-declared

The Media Rating Council (MRC), a US-based nonprofit that manages accreditation for media research and rating purposes, defines “Domain and App misrepresentation”, including “falsified domain / site location”, as a form of Sophisticated Invalid Traffic (SIVT). The Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) Europe, a tradegroup, describes “site fraud” and domain spoofing as one of the more common forms of ad fraud. According to the IAB, “Domain spoofing fraud [...] is often challenging to detect and prevent. With a simple line of code, fraudsters can change the URL of a site to make advertisers think lower quality sites (e.g., copyright infringement, gambling, pornography etc.) are reputable publishers.”

According to eMarketer, “Domain spoofing is probably the most common type of ad fraud, and involves the fraudulent party disguising its URL or domain as another”.

Integral Ad Science (IAS), an ad verification company, lists several types of ad fraud in their Ad Fraud 101 guide. The guide asks “So, what exactly is ad fraud?”, and lists several possibilities. One of these explainers says: “Serving ads on a site other than the one provided in an RTB request—this is known as domain spoofing”.

Source: IAS_Ad-Fraud-101-Guide_UK.pdf

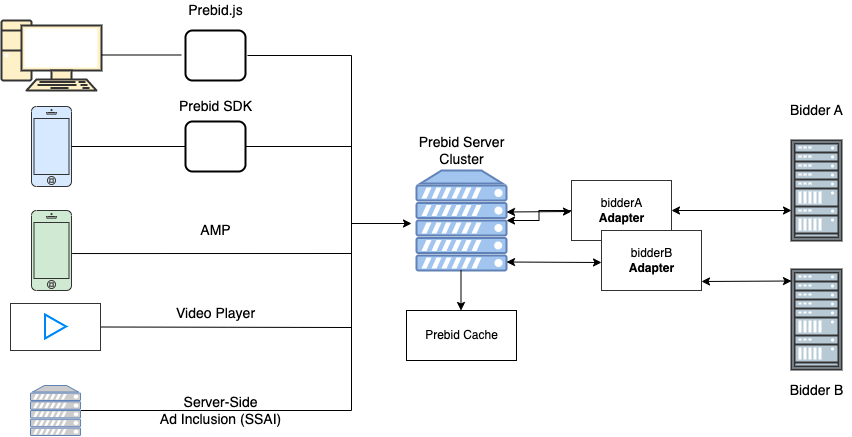

Forbes appears to utilize Prebid Server. Prebid Server is an open-source solution for server-to-server header bidding.

Illustration of Prebid server. Source: Prebid.org

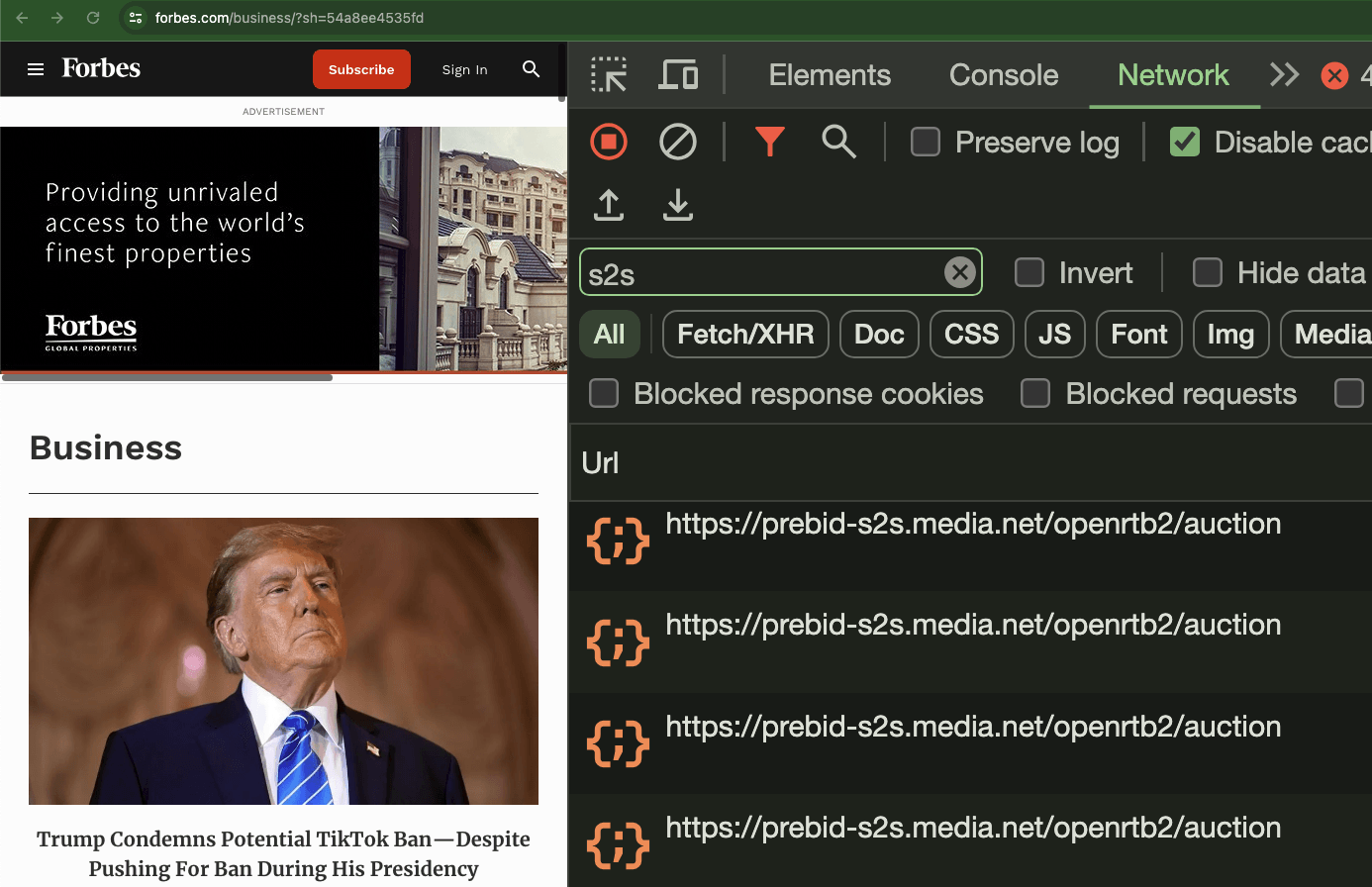

Forbes appears to utilize Media.net’s Server-to-Server Prebid solution as of 2024. Media.net is an ad tech company.

Adexchanger editor Sarah Sluis wrote in 2016 “Media.net started helping publishers move their header bidding partners to a speedier server-to-server configuration, which has since attracted publishers like The Atlantic, Forbes, The New York Times and WebMD” (emphasis added).

Adexchanger reported: “Forbes, for example, said Media.net has offered up more data beyond its dashboard. “If I ask for it, I get it,” said Achir Kalra, SVP of revenue and strategic operations at Forbes. Contract terms ensure fee transparency, he added [...] While header bidding has been adopted by publishers large and small, Kalra predicts the largest publishers will move to server-side bidding first.”

Screenshot of Chrome Developer Tools’ Network tab open on forbes.com, showing ad requests made to “prebid-s2s.media.net/openrtb/auction”, which is Media.net’s server-to-server Prebid implementation.

According to Adexchanger, “Media.net’s server-side platform also fields demand from a publication’s other exchange partners, including supply-side platforms such as AppNexus.”

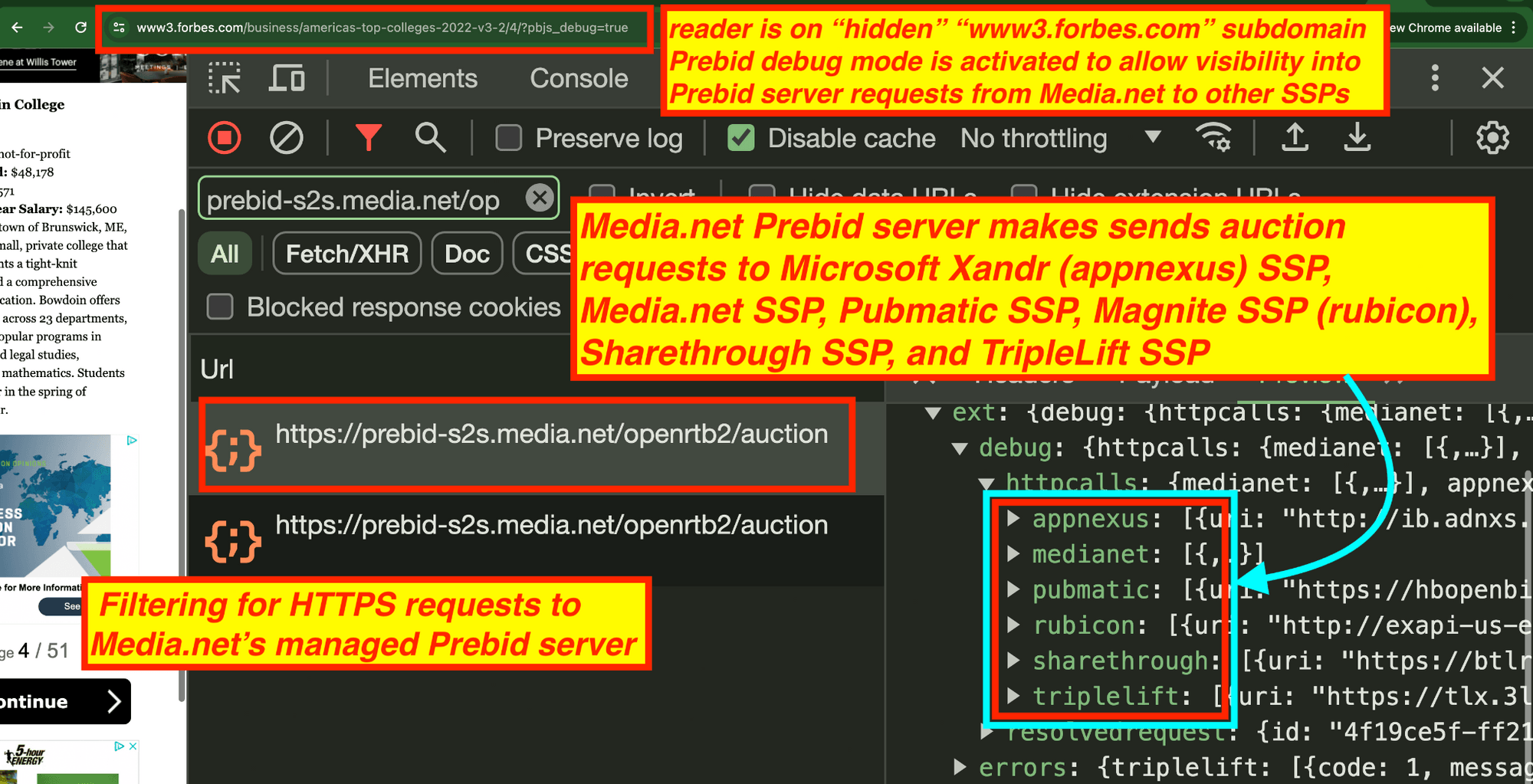

One can verify this in 2024 by visiting either the forbes.com or the “hidden” “www3.forbes.com” subdomain and observing HTTPS requests to prebid-s2s.media.net/openrtb2/auction, which is a Media.net managed Prebid server. One can use the Prebid server’s debug mode (activated by appending the query string “pbjs_debug=true” in the URL browser bar to observe server side requests made by Media.net’s Prebid server to various SSPs. The screenshot below shows Chrome Devtools filtered for HTTPS requests to “https://prebid-s2s.media.net/openrtb2/auction” and uses debug mode to show that Media.net Prebid server makes ad auction requests to Microsoft Xandr (fka Appnexus) SSP, Media.net SSP, Pubmatic SSP, Magnite SSP (“rubicon”), Sharethrough, and Triplelift.

Screenshot of https://www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/4/?pbjs_debug=true, with Chrome Developer Tools’ “Network” tab open. The “pbjs_debug=true” query string parameter in the URL instructs Prebid server to send back additional reporting logs to the browser. These logs show that Forbes uses media.net for its Prebid server, and that the Media.net managed Prebid server makes ad auction requests to Microsoft Xandr (“appnexus”), Media.net SSP, Pubmatic, Magnite SSP (“rubicon”), Sharethrough SSP, and TripleLift SSP.

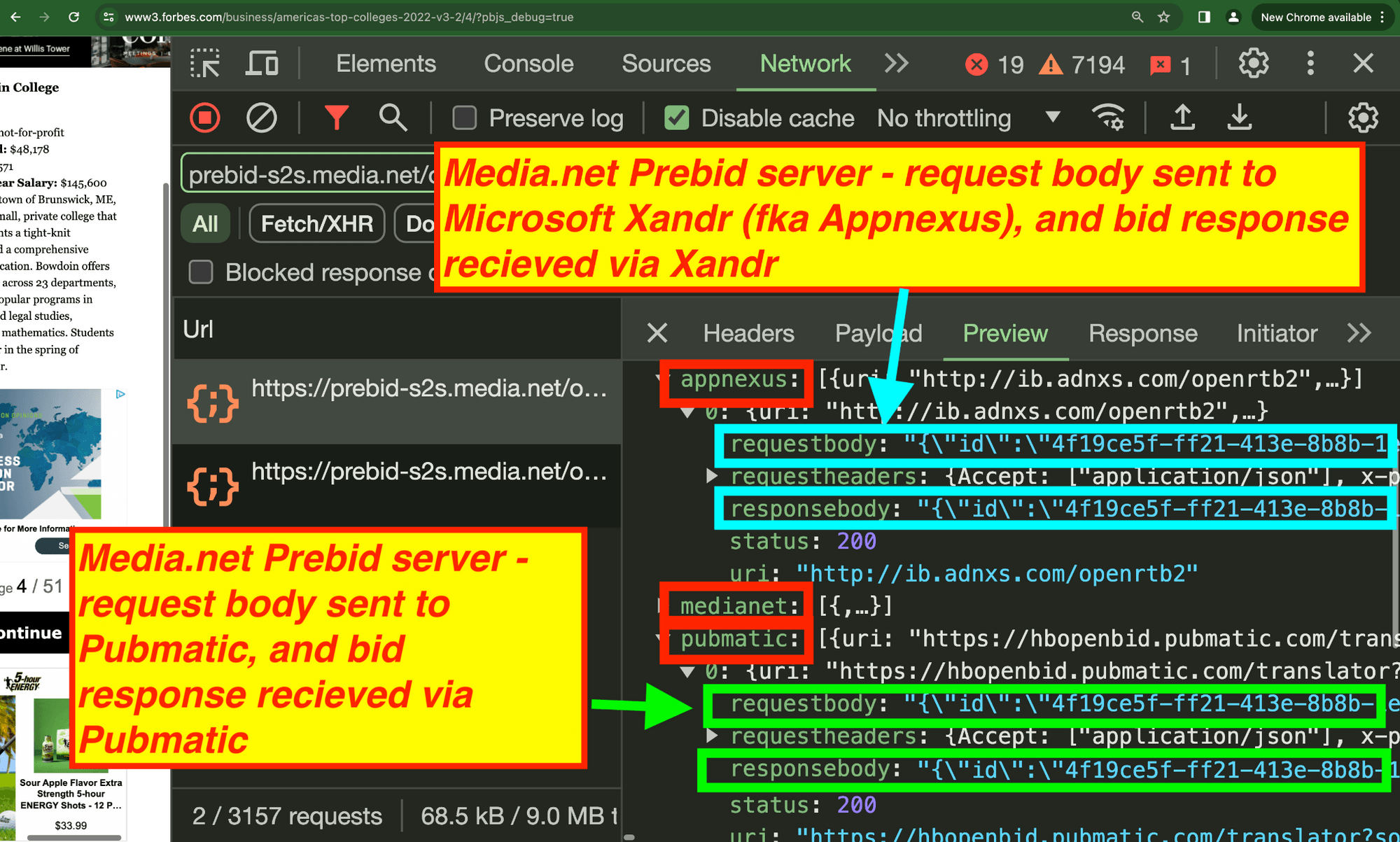

Screenshot of https://www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/5/?pbjs_debug=true, with Chrome Developer Tools’ “Network” tab open. The “pbjs_debug=true” query string parameter in the URL instructs Prebid server to send back additional reporting logs to the browser. One can see the ad auction request bodies and bid responses transacted via Microsoft Xandr SSP (“appnexus”) and Pubmatic SSP.

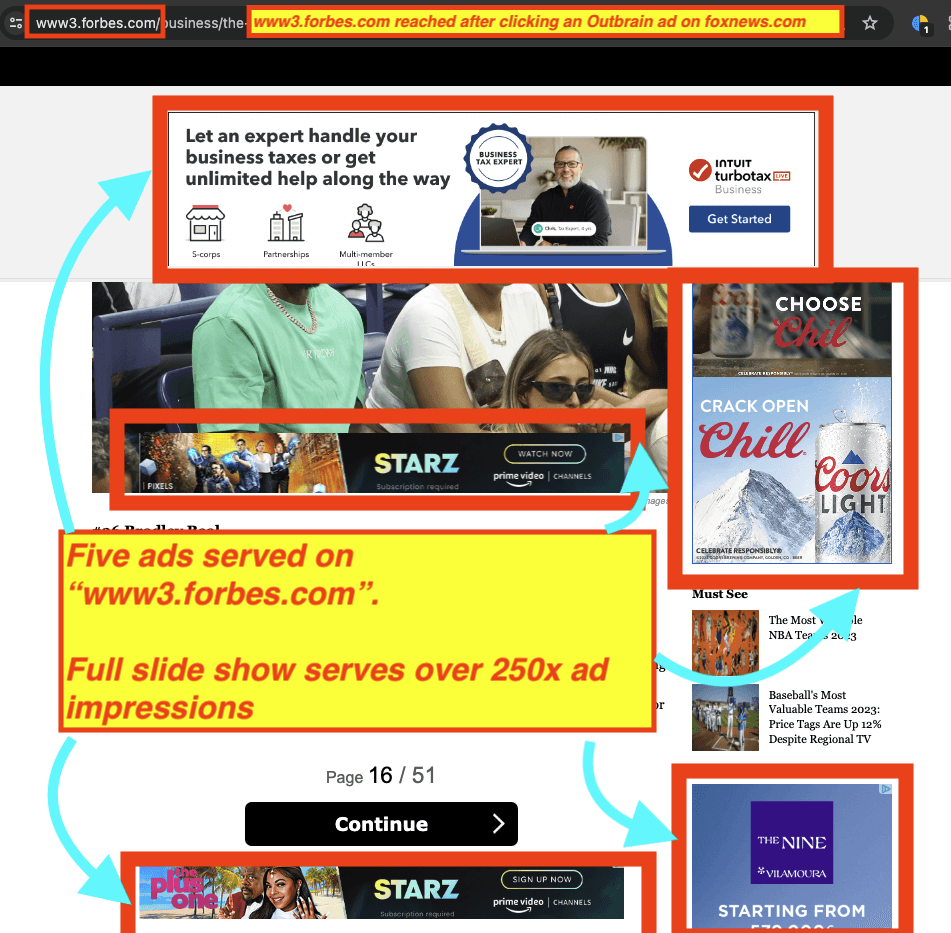

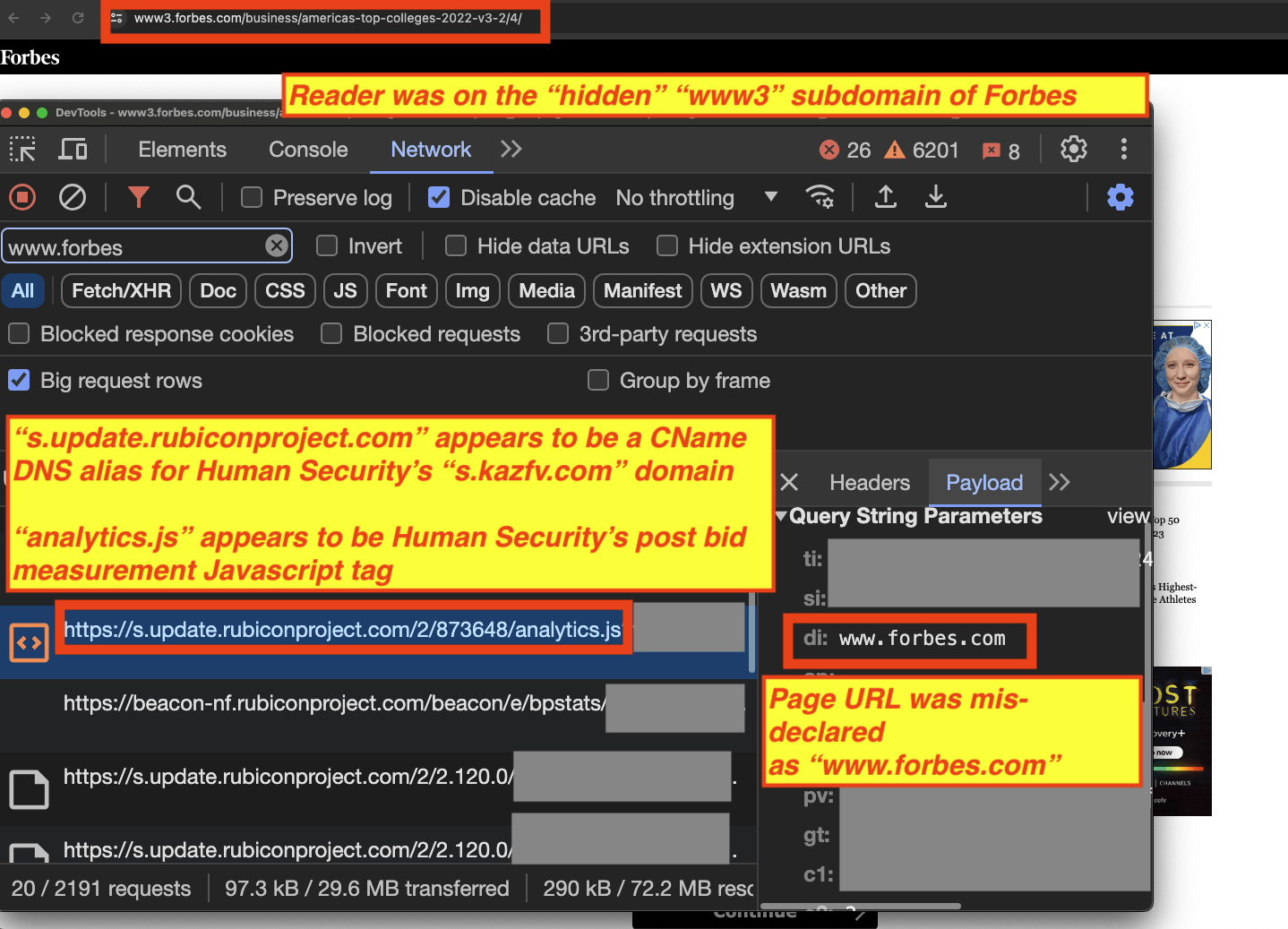

Examining the request bodies of the ad auction requests sent to the six SSPs by Media.net’s Prebid server shows that for at least four of the six SSPs, the data sent from the Prebid server to the SSPs contains mis-declared and truncated page information.

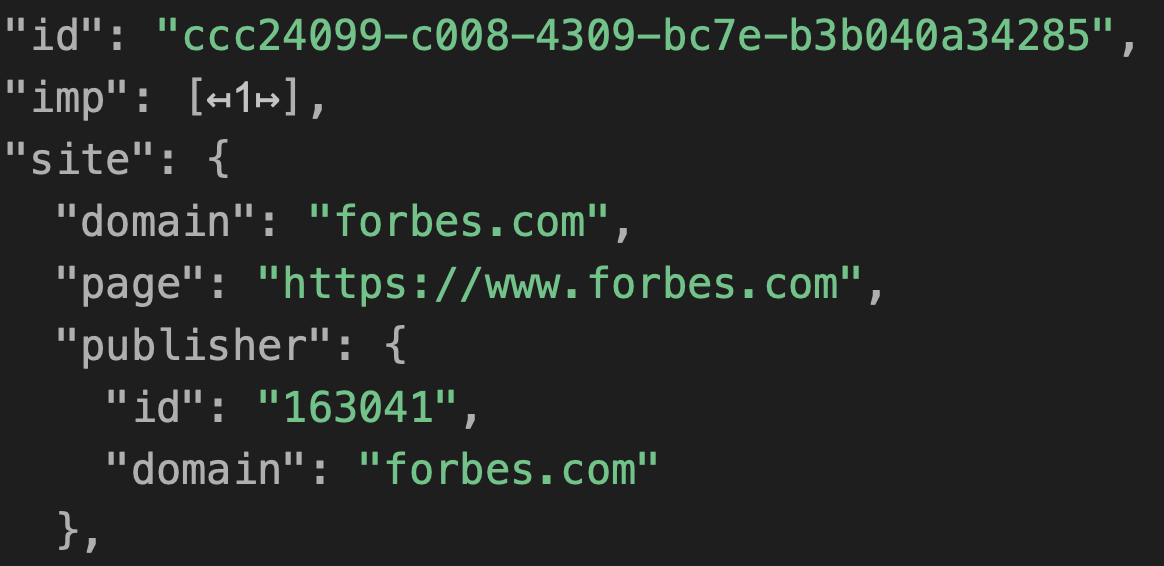

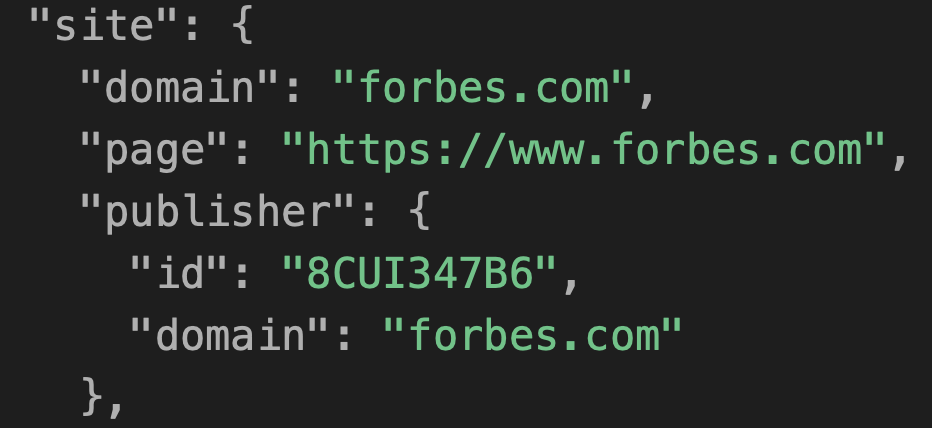

For example, in the screenshot below of the request sent by Media.net’s Prebid server on “www3.forbes.com” to Microsoft Xandr, one can see that the “site” “page” attribute is truncated (the full page URL was removed), and the subdomain was changed from “www3.forbes.com” to the “normal” “www.forbes.com”

Request body sent to Microsoft Xandr via Media.net’s Prebid server on “www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/5/”. The “site” “page” attribute was truncated and mis-declared as “https://www.forbes.com”.

As a second example, in the screenshot below of the request sent by Media.net’s Prebid server on “www3.forbes.com” to Microsoft Xandr, one can see that the “site” “page” attribute is truncated (the full page URL was removed), and the subdomain was changed from “www3.forbes.com” to the “normal” “www.forbes.com”.

Request body sent to Pubmatic via Media.net’s Prebid server on “www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/5/”. The “site” “page” attribute was truncated and mis-declared as “https://www.forbes.com”. The ad was transacted via Pubmatic seller ID 163041

The bid response transacted via Pubmatic shows the ad, which was bid on by Publicis-owned Epsilon Conversant, had the declared bid URL declared as “www.forbes.com”, rather than “www3.forbes.com”.

Bid response body from Pubmatic via Media.net Prebid server. The bid response from Epsilon Conversant shows that the ad auction declared page was mis-declared as “www.forbes.com”

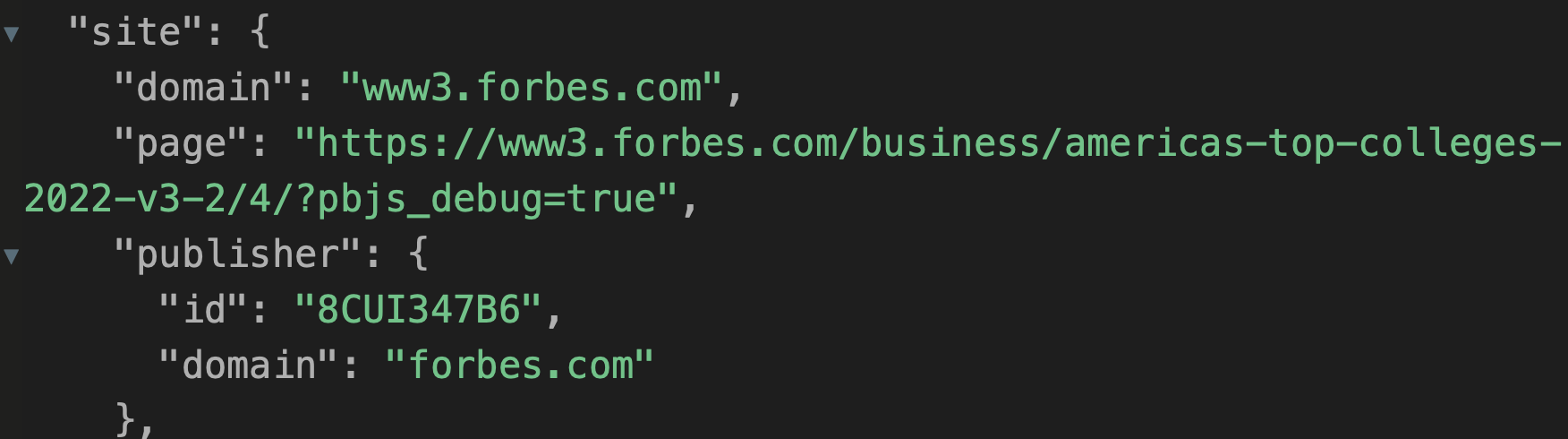

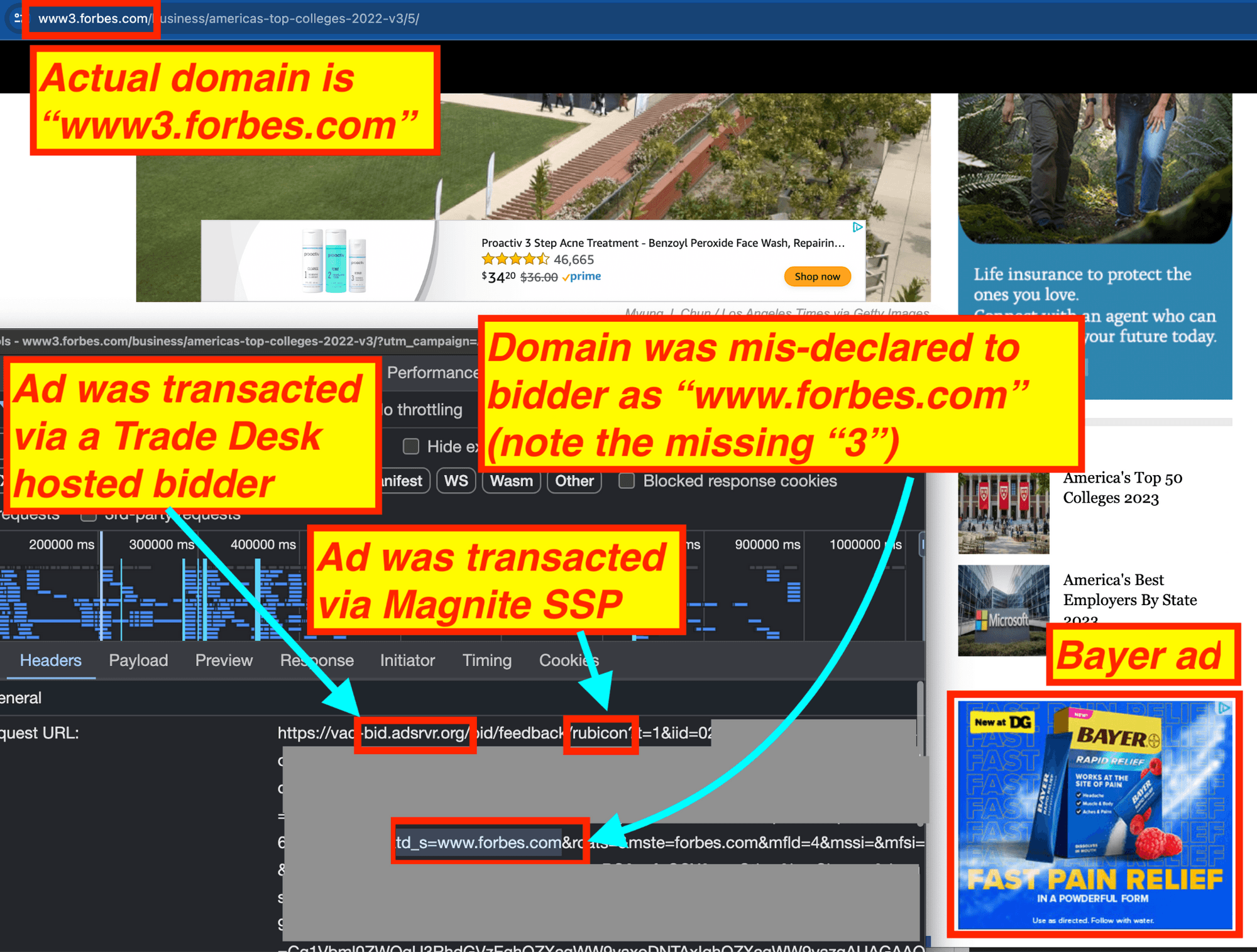

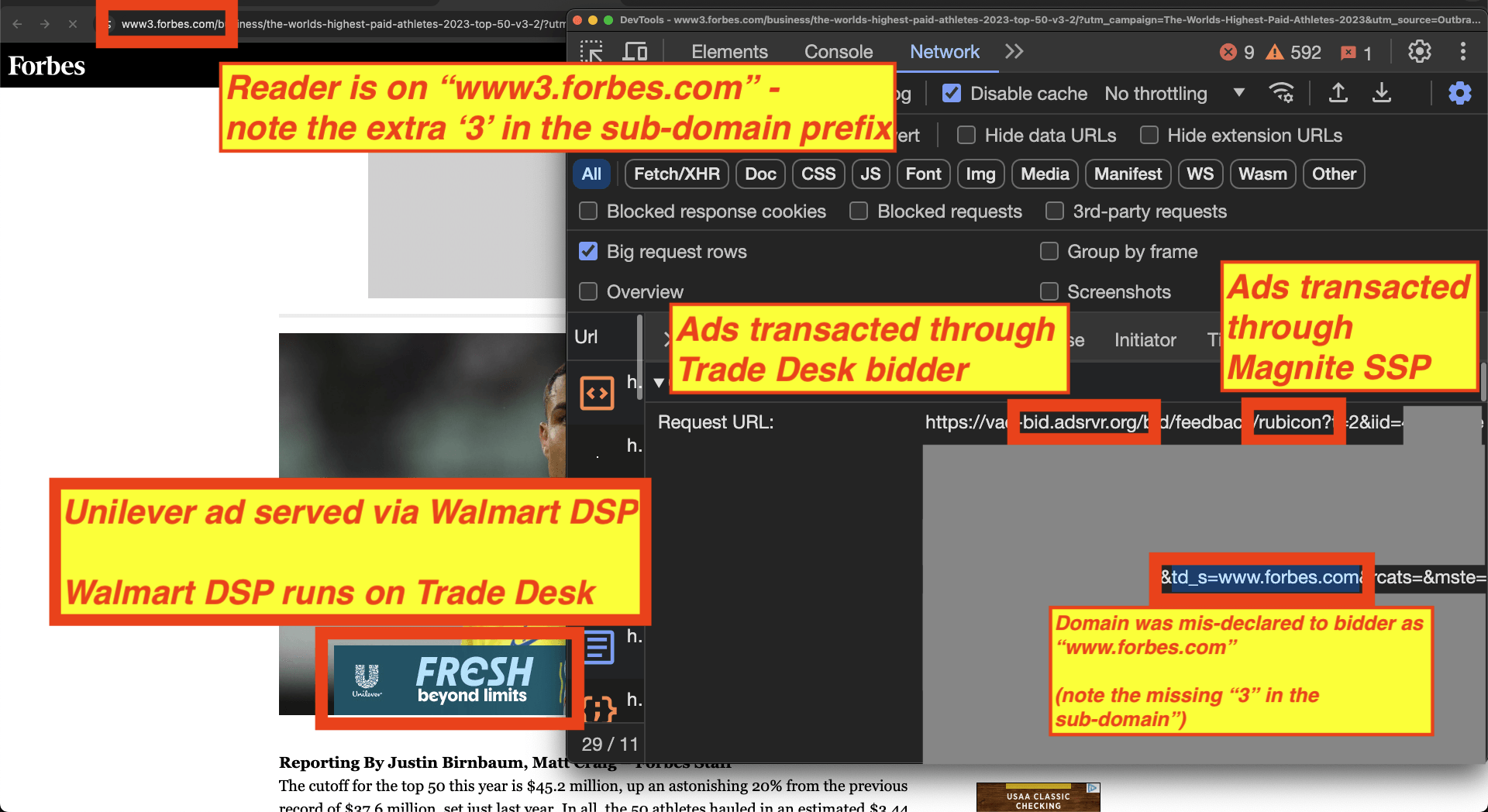

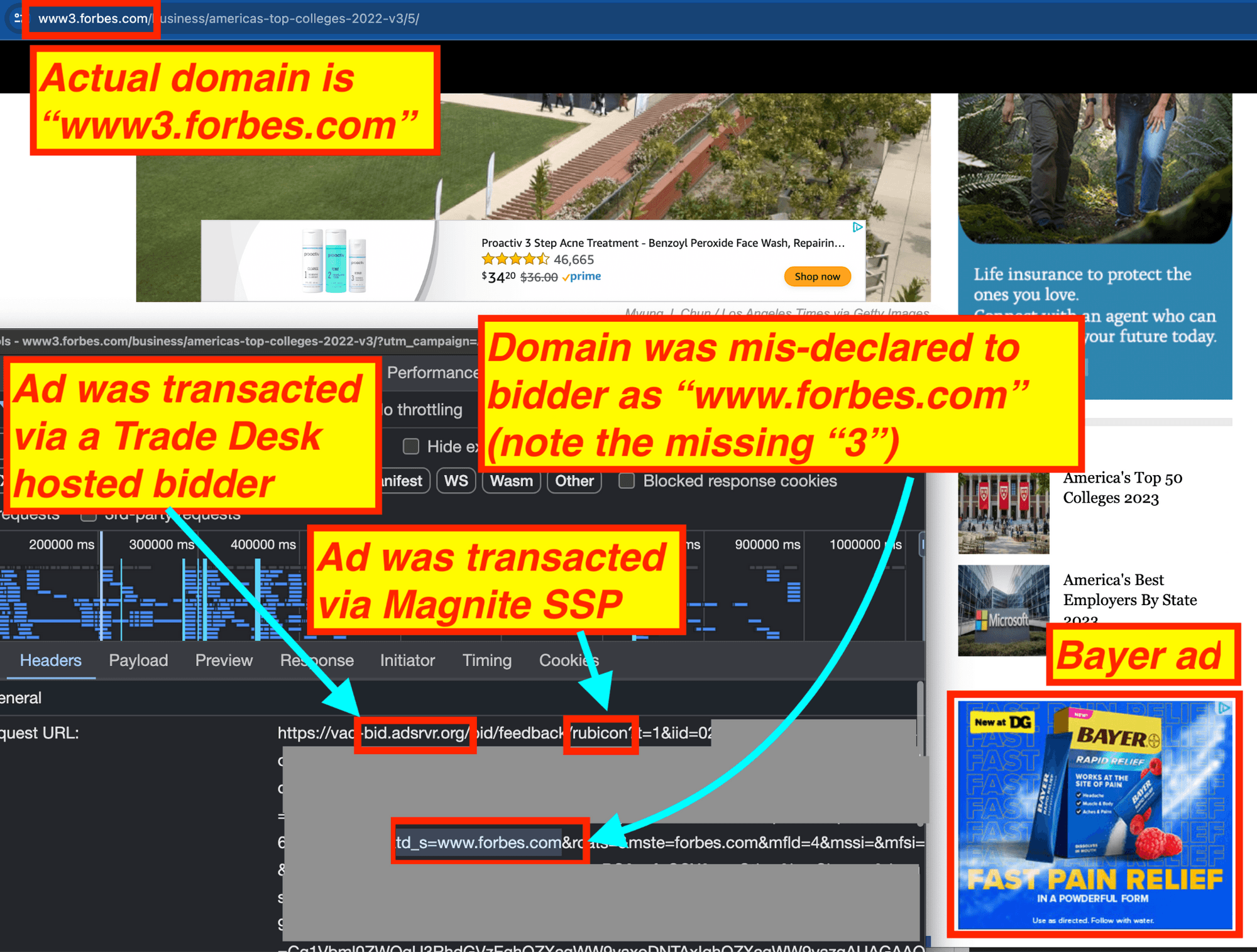

As a third example, in the screenshot below of the request sent by Media.net’s Prebid server on “www3.forbes.com” to Magnite SSP, one can see that the “site” “page” attribute is truncated (the full page URL was removed), and the subdomain was changed from “www3.forbes.com” to the “normal” “www.forbes.com”

Request body sent to Magnite via Media.net’s Prebid server on “www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/5/”. The “site” “page” attribute was truncated and mis-declared as “https://www.forbes.com”. The ad was transacted via Magnite seller ID 12924

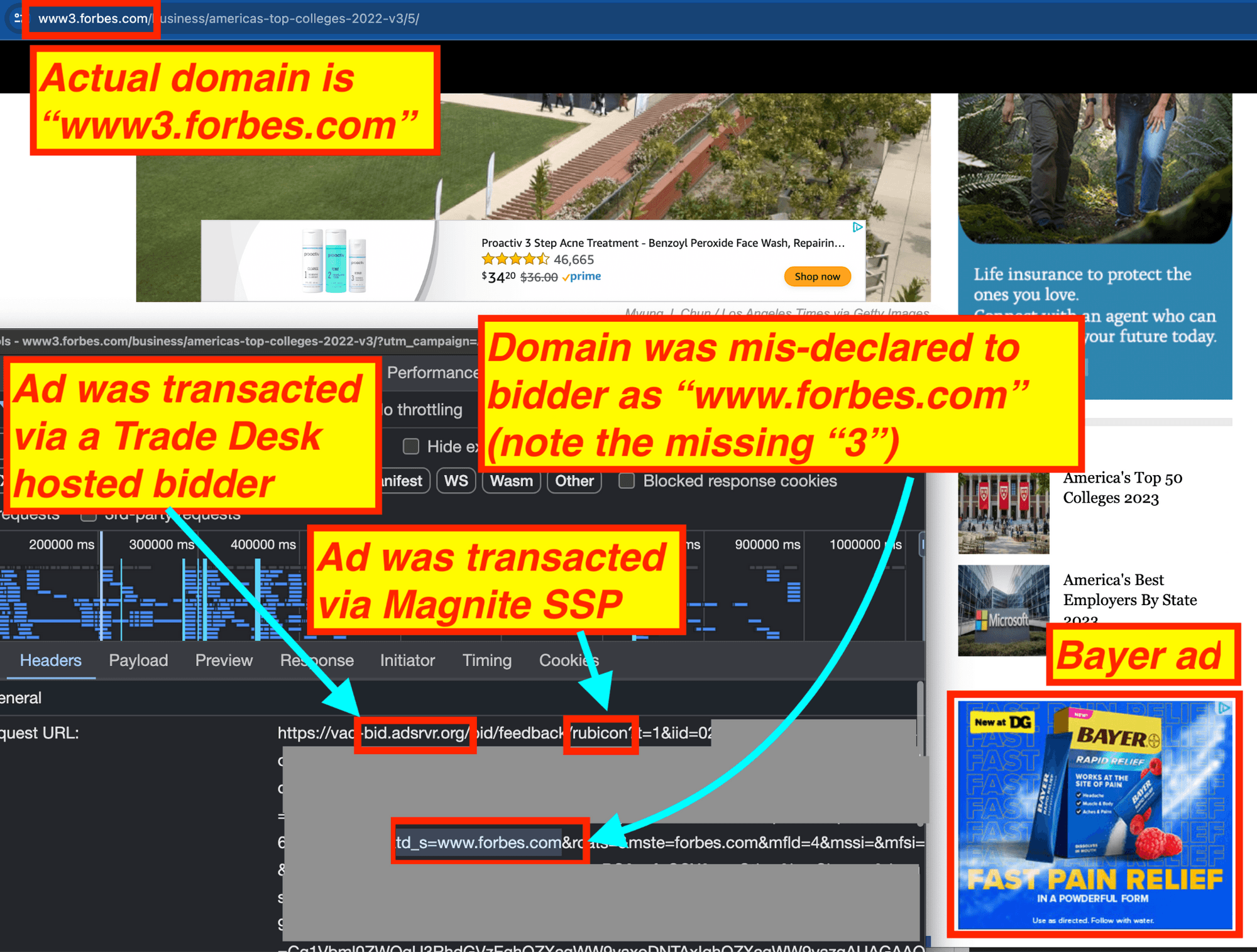

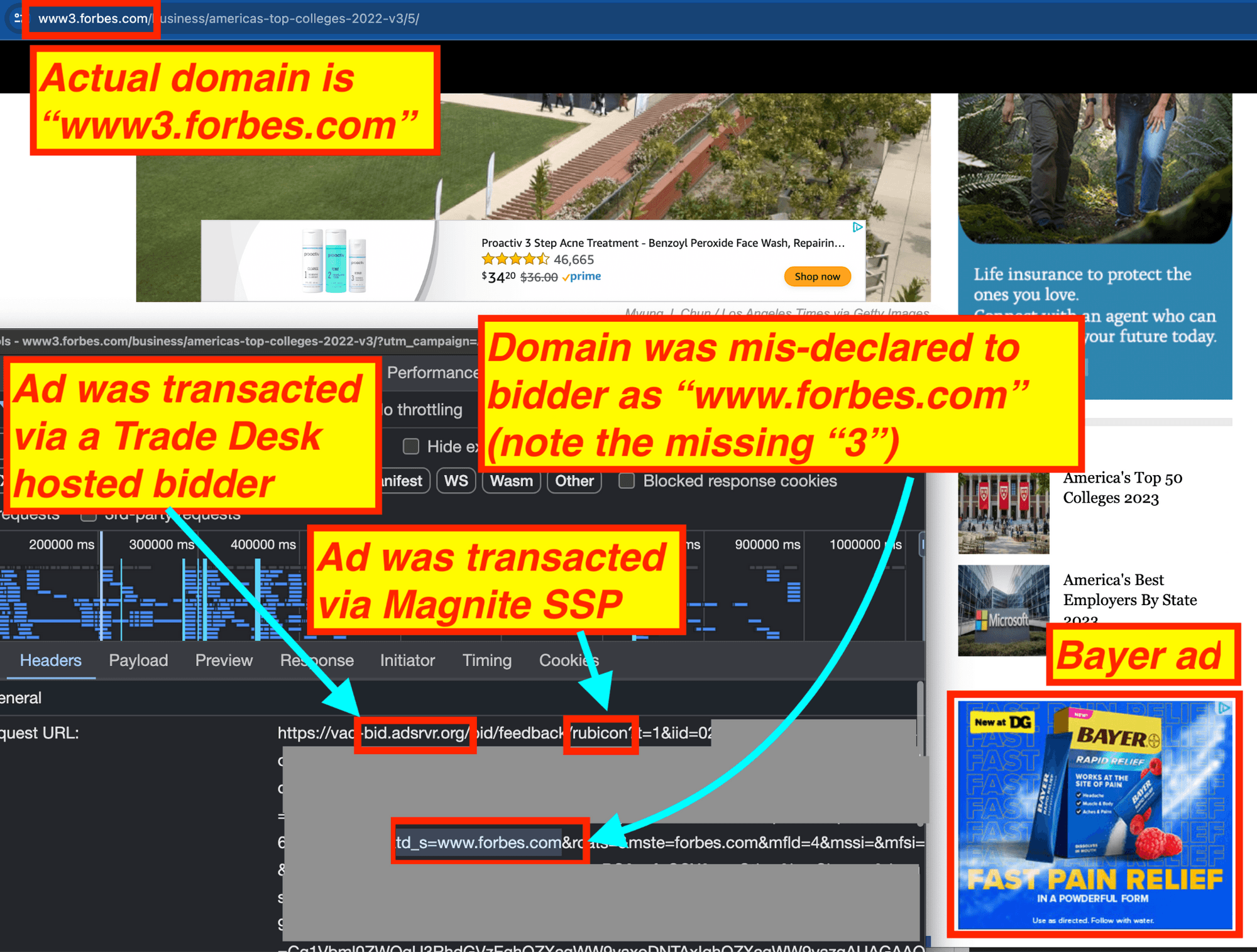

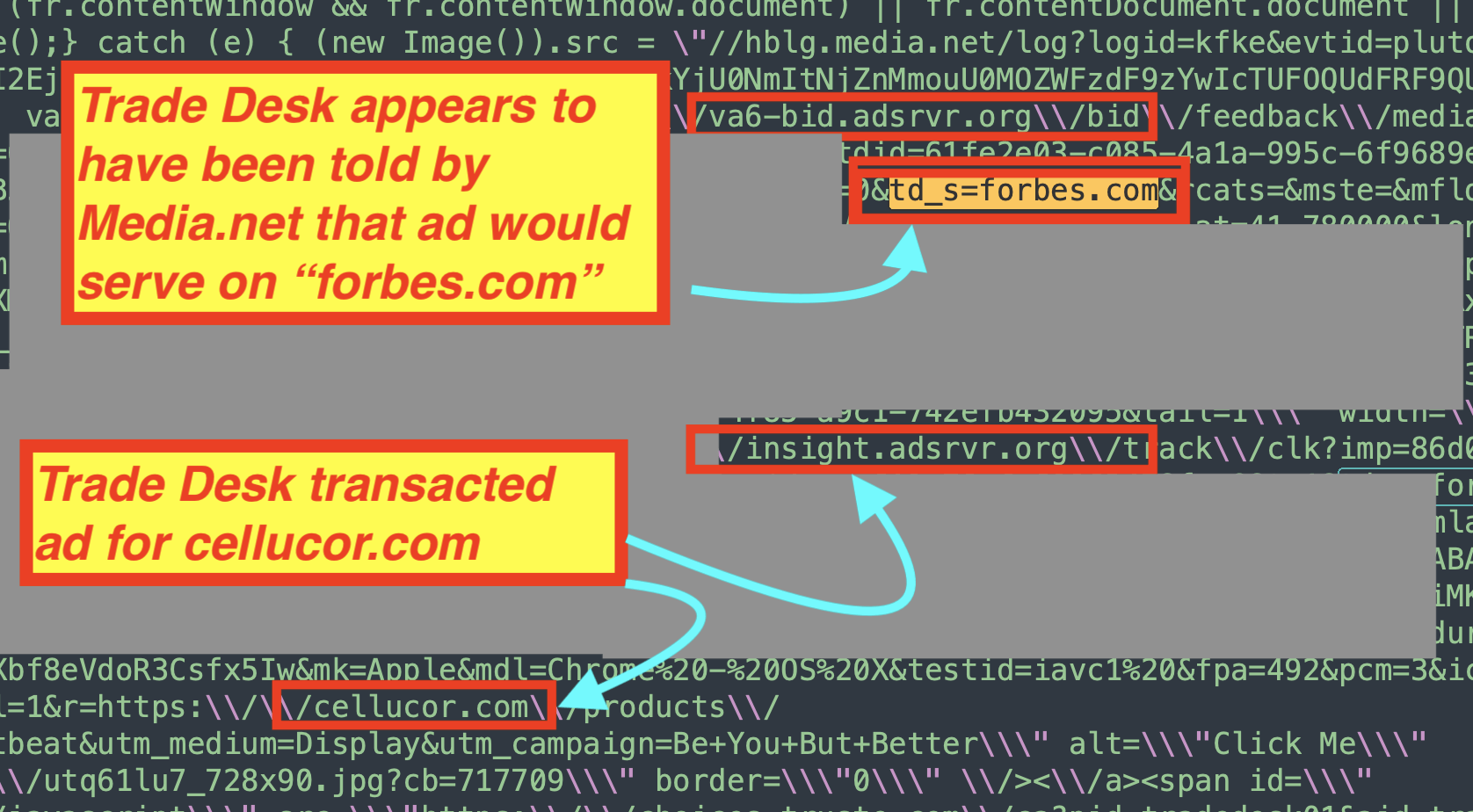

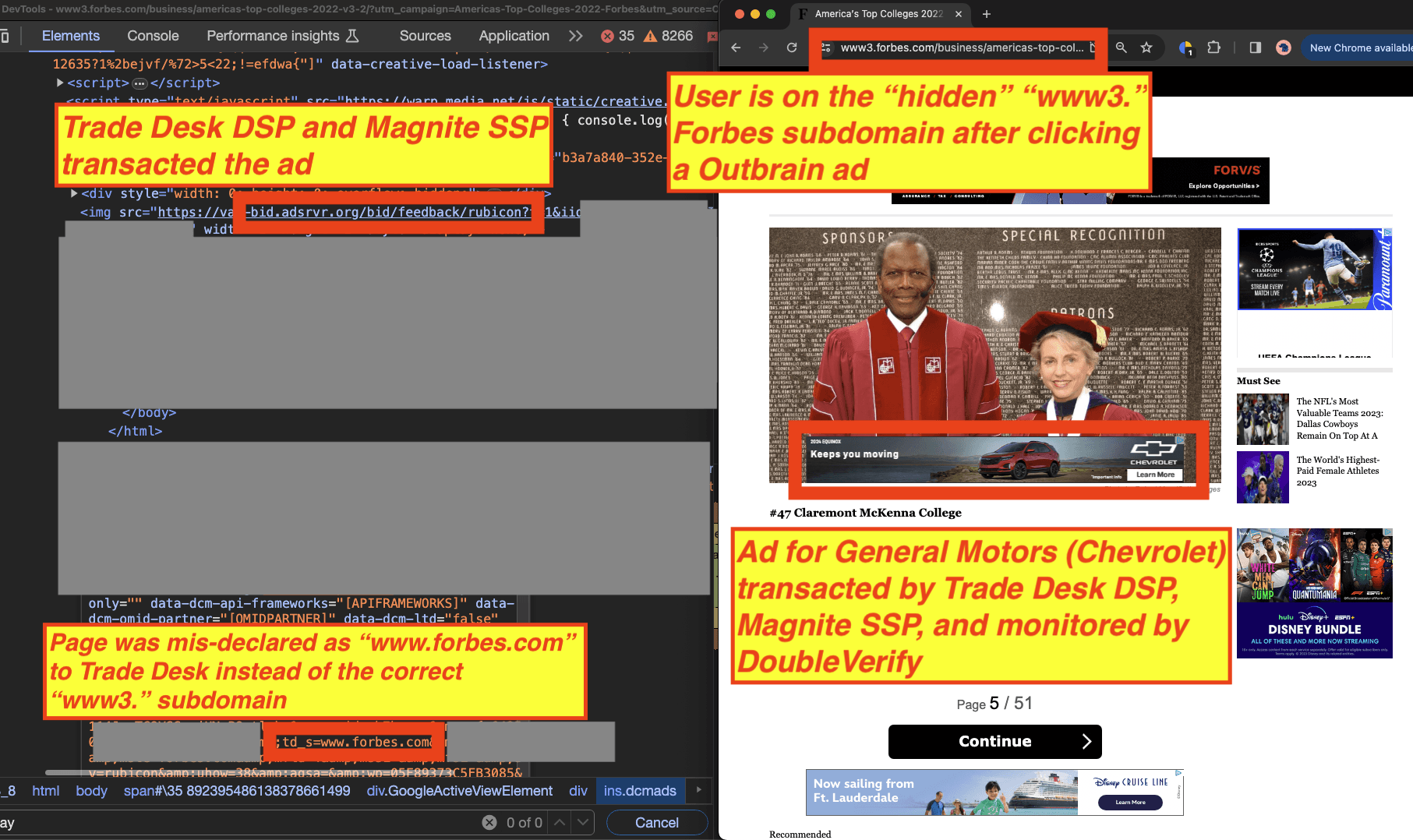

Examining bid responses from DSPs such as the Trade Desk that transacted via Magnite seller ID 12924 and Media.net Prebid server confirm that Trade Desk’s bidder was apparently told at auction time the ad would be serving on “www.forbes.com”; not the actual “www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/5/”.

Request body sent to Triplelift via server-to-server Prebid media.net

Request body sent to Triplelift via Media.net’s Prebid server on “www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/5/”. The “site” “page” attribute was truncated and mis-declared as “https://www.forbes.com”.

A bid response from Triplelift’s header bidding endpoint to Media.net’s Prebid server appears to show that Trade Desk bid on behalf of the brand Progressive. The source code of the bid response suggests that the page URL was mis-declared to Trade Desk’s bidder as “www.forbes.com”, rather than the actual “www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/5/”.

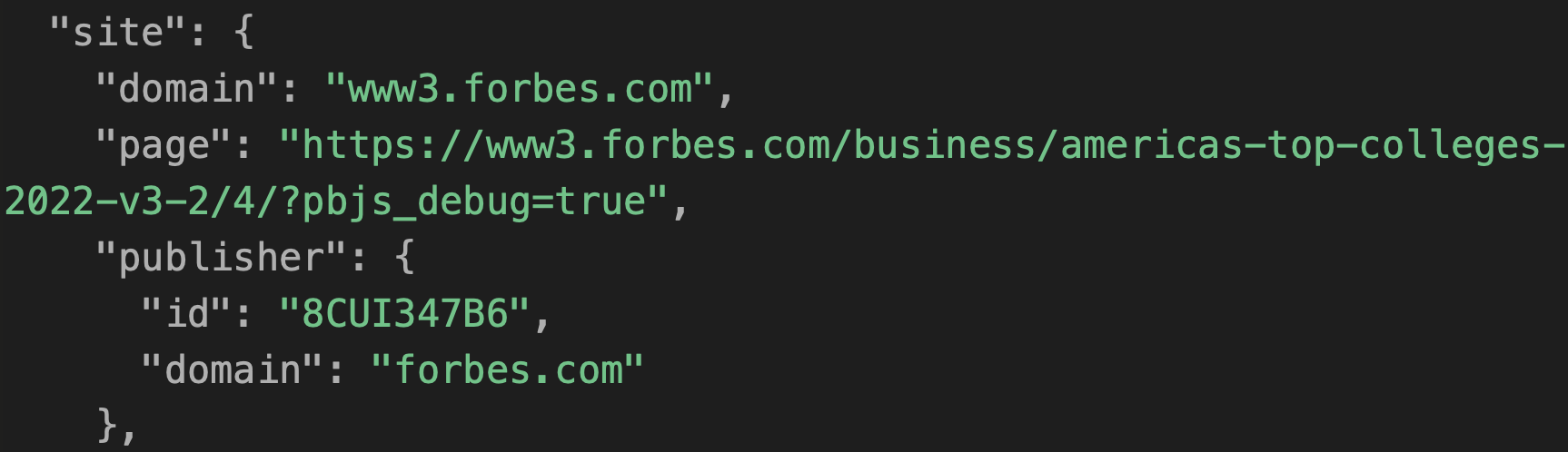

Interestingly, in the screenshot below of the request sent by Media.net’s Prebid server on “www3.forbes.com” to Media.net SSP, one can see that the “site” “page” attribute is neither truncated nor changed. The site page attribute is correctly declared as “www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/4/?pbjs_debug=true”.

Request body sent to Media.net via Media.net’s Prebid server on “www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/4/?pbjs_debug=true”. The “site” “page” attribute was correctly declared.

However, Examining bid responses from DSPs such as the Trade Desk that transacted via Media.net SSP and Media.net Prebid server suggest Trade Desk’s bidder was apparently told at auction time that the ad would be serving on “www.forbes.com”; not the actual “www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/4/?pbjs_debug=true”.

Response body returned from Media.net SSP via Media.net’s Prebid server.

In the screenshot below of the request sent by Media.net’s Prebid server on “www3.forbes.com” to ShareThrough SSP, one can see that the “site” “page” attribute is neither truncated nor changed. The site page attribute is correctly declared as “www3.forbes.com/business/americas-top-colleges-2022-v3-2/4/?pbjs_debug=true”.

Request body sent to Sharethrough via Media.net’s Prebid server. The “site” “page” attribute was correctly declared.

Screenshot of a Shopify ad transacted via ShareThrough SSP on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of forbes.com

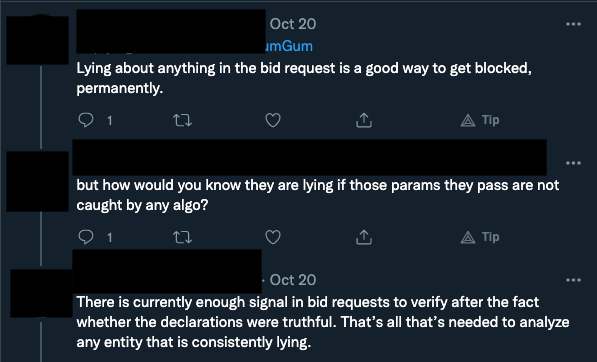

It is unclear why the ad auction requests sent from Media.net’s Prebid server to various header bidding endpoints appear to contain mis-declared page information. It is unclear why TripleLift, Magnite, Pubmatic, Media.net, and Microsoft Xandr SSPs appear to relay mis-declared page information to DSPs such as Trade Desk or Epsilon Conversant. This report cannot comment on whether the page mis-declaration was set up intentionally or due to an oversight.

One ad tech software engineer who is highly familiar with Prebid server code told Adalytics: “It takes substantial effort to fork Prebid Server to send different information to different bidders; it is complicated software and forks are difficult to maintain. On the pages demonstrated, one can see Prebid Server received the correct site.page and passed them faithfully to the Sharethrough and Media.net bidding endpoints while other endpoints receive the modified value. I am not aware of this functionality being possible in the open source as Prebid Code of Conduct states 'the Auction Layer must pass available bid request information to each configured demand partner, subject to Publisher configuration.' Prebid Server documentation on stored portions of the bid request states 'HTTP request properties will overwrite the Stored Request ones," but here we clearly see the site.page property of the request to PBS being malformed before sent on.”

Furthermore, this report cannot assert whether Forbes, Media.net, or some other entity is responsible for the apparent page mis-declarations in ad auctions.

Results: Supply side platforms observed transacting ads on “www3.forbes.com”

TAG “Certified against Fraud” SSPs observed transacting mis-declared ad inventory on “www3.” forbes.com

Given the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of forbes.com appears to exhibit many behavior’s consistent with the ANA’s, ISBA’s, 4A’s, WFA’s, Jounce Media’s, and DeepSee.io’s definition of “Made for Advertising” (and/or “Made for Arbitrage), this study sought to qualitatively observe which Supply Side Platforms (SSPs) were transacting ad inventory on the “hidden” and/or mis-declared “www3.” subdomain.

Many SSPs which transact ads on www3.forbes.com, including some that were observed transacting mis-declared “www3.” ad inventory, appear to be “Certified against fraud” by the Trustworthy Accountability Group (TAG), a tradegroup. TAG Certified Against Fraud Guidelines specifically state:

“To achieve the Certified Against Fraud Seal, any participating company must ensure that 100% of the monetizable transactions (including impressions, clicks, conversions, etc.) that it handles are filtered for both general invalid traffic (GIVT) and sophisticated invalid traffic (SIVT) in a manner compliant with a TAG-recognized standard for IVT detection and removal as referenced in Appendix A.”

Source: TAG Certified Against Fraud Guidelines - Section 4.5

Appendix A states: “A company choosing to comply with the requirement by accreditation to a TAG-Recognized standard must provide evidence of accreditation via the provisions of the following TAG recognized standards as follows: [...] Media Rating Council’s (MRC) Invalid Traffic (IVT) Detection and Filtration Guidelines Addendum.”

Source: TAG Certified Against Fraud Guidelines - Appendix A

The Media Rating Council’s IVT Detection and Filtration Guidelines Addendum states: “The second category, herein referred to as “Sophisticated Invalid Traffic” or SIVT, consists of more difficult to detect situations that require advanced analytics, multi-point corroboration/coordination, significant human intervention, etc., to analyze and identify. Key examples are: [...] Domain and App misrepresentation: App ID spoofing, domain laundering and falsified domain / site location”.

Source: Media Ratings Council’s IVT Detection and Filtration Guidelines Addendum

Several SSPs observed transacting mis-declared “www3.” Forbes ad inventory appear to be TAG Certified Against Fraud. For example, the TAG Registry show that Magnite, Pubmatic, Microsoft Xandr (fka Appnexus), and TripleLift have all received the “Certified Against Fraud” seal.

Screenshot of the TAG Registry, showing that Magnite has achieved the “Certified Against Fraud seal”. Magnite was observed transacting mis-declared “www3.” Forbes ad inventory.

Microsoft Xandr and Media.net have also achieved the TAG Certified For Transparency seal.

According to TAG, the “mission of the TAG Certified for Transparency program is to give trusted businesses industry wide recognition in their efforts for achieving high levels of transparency and accountability across their operations.”

As described earlier, it appears that several SSPs were observed transacting or transmitting mis-declared page URL data to DSPs such as The Trade Desk.

This observational study noted that ad auction requests from the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain that were transmitted via the Media.net Prebid server and several SSPs to DSPs such as the Trade Desk appear to contain mis-declared page URL information. The list of SSPs that appeared to transmit mis-declared page URL information to Trade Desk and other DSPs includes:

Magnite SSP

TripleLift SSP

Microsoft Xandr SSP

Pubmatic SSP

Media.net SSP

Screenshot of source code for an ad observed on “www3.” subdomain of Forbes. The ad auction request was transmitted by Media.net Prebid server and TripleLift SSP, and was bid upon by Trade Desk DSP. The source code of the Trade Desk ad suggests that Trade Desk was mis-informed that the ad would be served on “www.forbes.com”, when in reality the ad was served on a specific page on “www3.forbes.com”.

Screenshot showing source code of a Bayer Claritin ad on “www3.” subdomain of Forbes. The source code of the ad shows it was transacted via Trade Desk DSP and TripleLift SSP. The ad source code suggests that the page URL was mis-declared to Trade Desk’s bidder as “www.forbes.com”, when in reality the user was on the “www3.” subdomain of Forbes.

Screenshot of HTTPS requests observed on “www3.” subdomain of Forbes. The ad auction request was transmitted by Media.net Prebid server and Magnite SSP, and was bid upon by Trade Desk DSP. The source code of the Trade Desk ad suggests that Trade Desk was mis-informed that the ad would be served on “www.forbes.com”, when in reality the ad was served on a specific page on “www3.forbes.com”.

Screenshot of a General Motors (Chevrolet) ad on the “www3.” subdomain of Forbes. The ad auction request was transmitted by Media.net Prebid server and Microsoft Xandr (fka Appnexus) SSP, and was bid upon by Trade Desk DSP. The source code of the Trade Desk ad suggests that Trade Desk was mis-informed that the ad would be served on “www.forbes.com”, when in reality the ad was served on a specific page on “www3.forbes.com”.

Screenshot of a General Motors (Chevrolet) ad observed on the “www3.” subdomain of Forbes. The ad auction request was transmitted by Media.net Prebid server and Magnite SSP, and was bid upon by Trade Desk DSP. The source code of the Trade Desk ad suggests that Trade Desk was mis-informed that the ad would be served on “www.forbes.com”, when in reality the ad was served on a specific page on “www3.forbes.com”. The ad contains measurement source code from DoubleVerify and Oracle Moat.

Screenshot of a General Motors (Chevrolet) ad observed on the “www3.” subdomain of Forbes. The ad auction request was transmitted by Media.net Prebid server and Magnite SSP, and was bid upon by Trade Desk DSP. The source code of the Trade Desk ad suggests that Trade Desk was mis-informed that the ad would be served on “www.forbes.com”, when in reality the ad was served on a specific page on “www3.forbes.com”. The ad contains measurement source code from DoubleVerify and Oracle Moat.

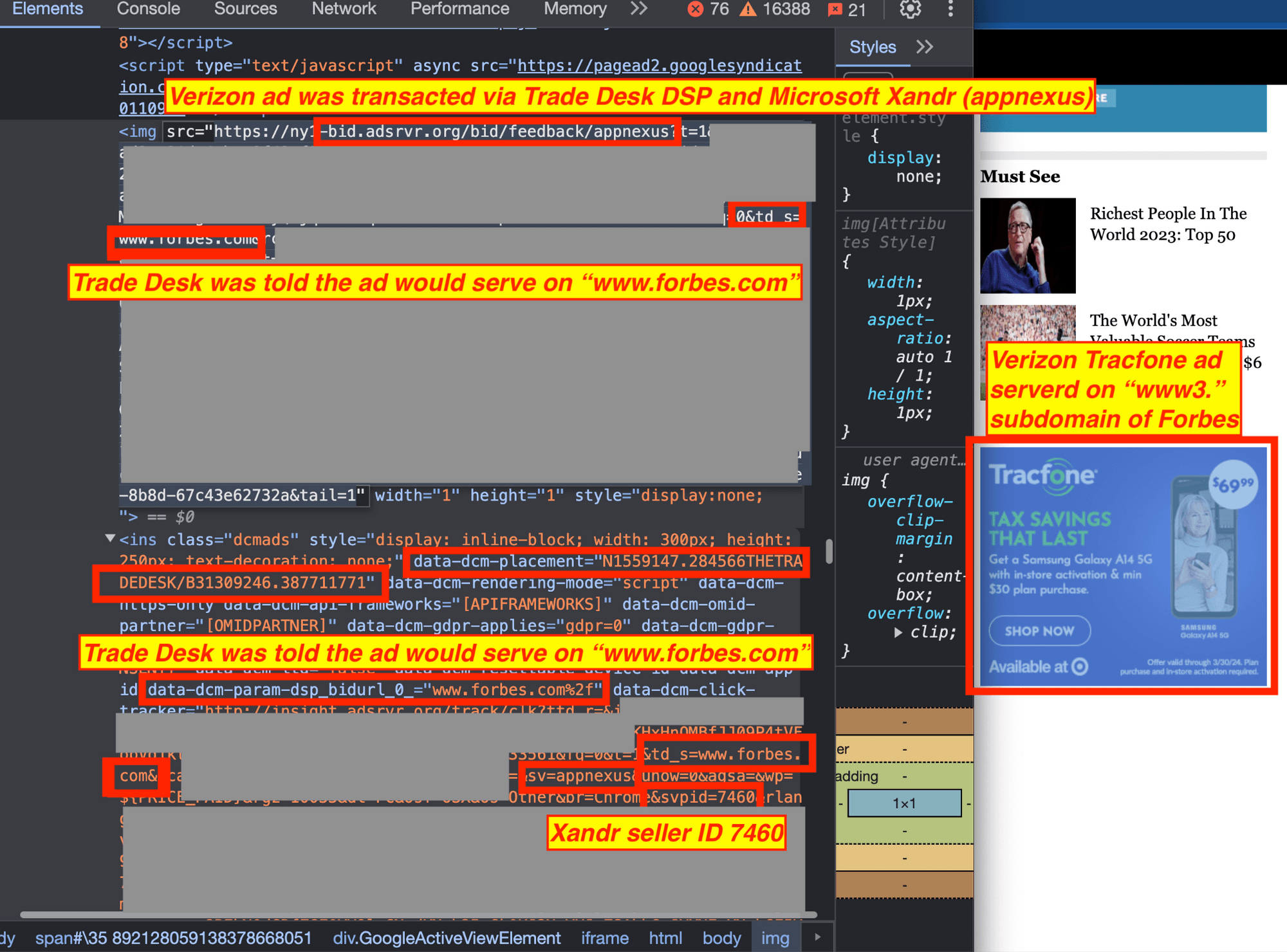

Screenshot of a Verizon Tracfone ad observed on the “www3.” subdomain of Forbes. The ad auction request was transmitted by Media.net Prebid server and Microsoft Xandr (appnexus) SSP, and was bid upon by Trade Desk DSP. The source code of the Trade Desk ad suggests that Trade Desk was mis-informed that the ad would be served on “www.forbes.com”, when in reality the ad was served on a specific page on “www3.forbes.com”.

Bid response body from Pubmatic via Media.net Prebid server. The bid response from Epsilon Conversant shows that the ad auction declared page was mis-declared as “www.forbes.com”

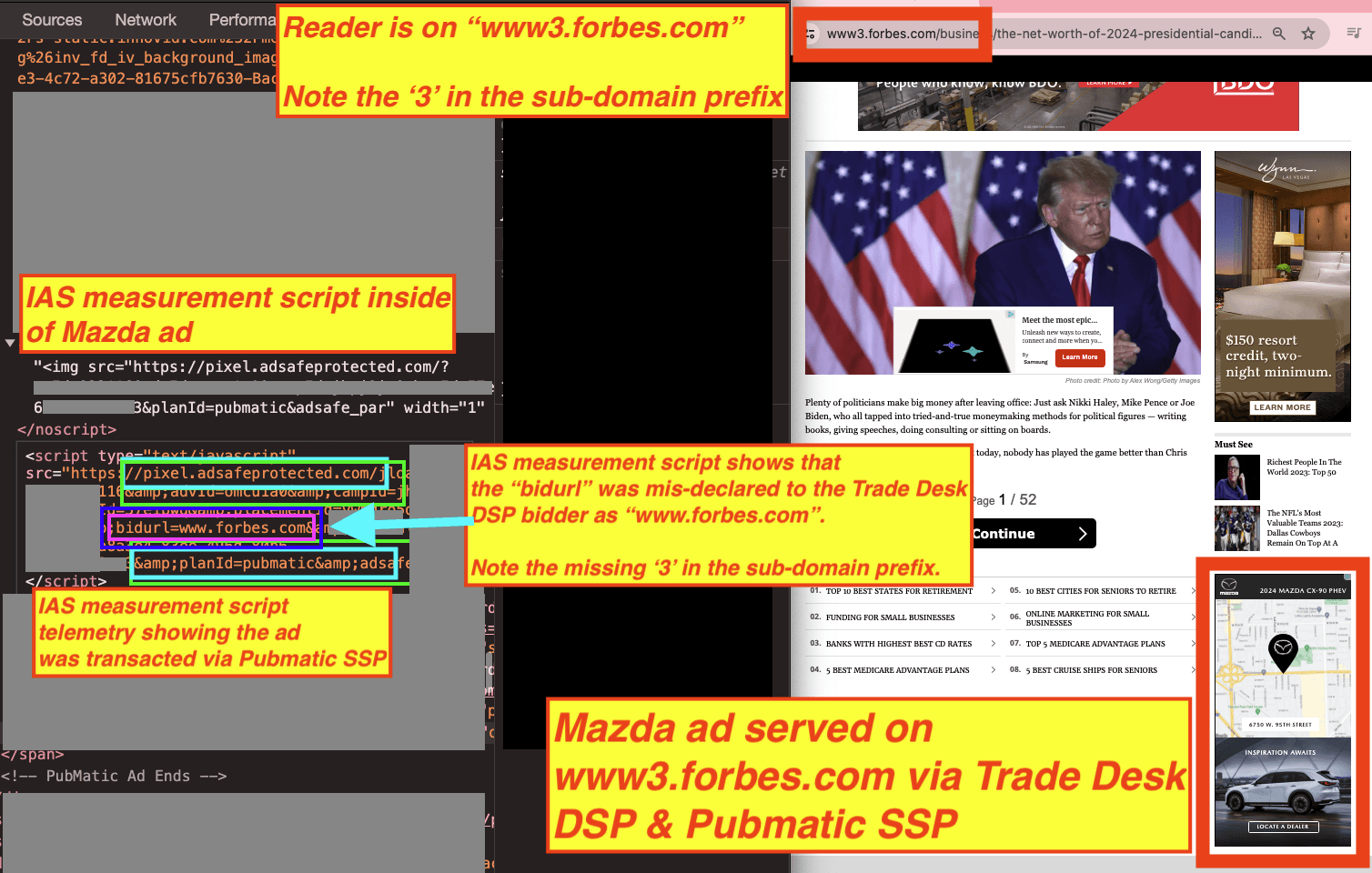

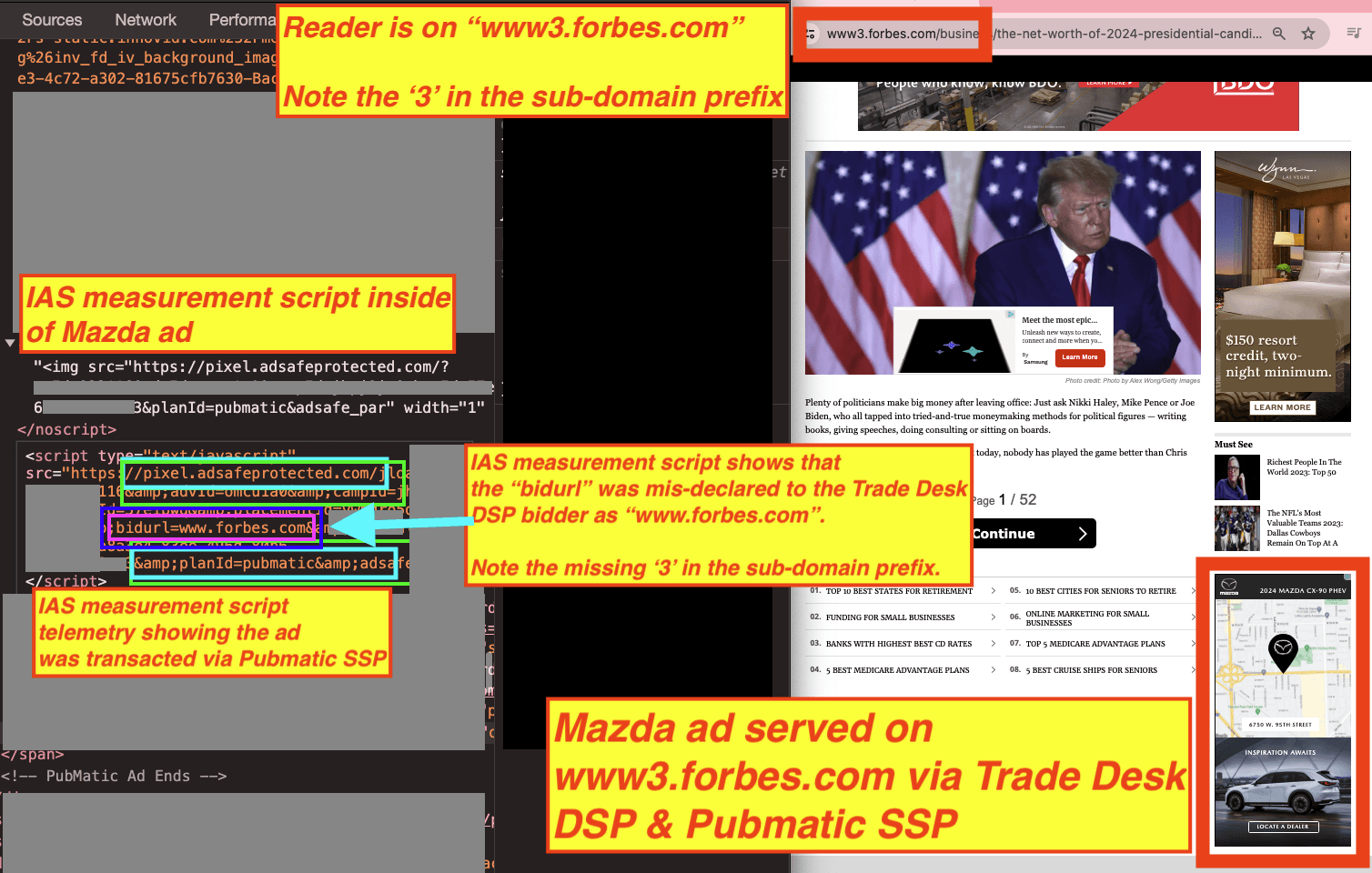

Screenshot of a Mazda ad observed on the “www3.” subdomain of Forbes. The ad auction request was transmitted by Media.net Prebid server and Pubmatic SSP, and was bid upon by Trade Desk DSP. The source code of the Trade Desk ad suggests that Trade Desk was mis-informed that the ad would be served on “www.forbes.com”, when in reality the ad was served on a specific page on “www3.forbes.com”.

Other SSPs were observed transmitting ad auction requests, but there was no observed evidence that these other SSPs were transmitting mis-declared page URLs. For example, ShareThrough was observed transmitting ad auction requests to DSPs from the “www3.” subdomain, but it did not appear to transmit mis-declared page URL data to DSPs. ShareThrough appeared to correctly transmit the full page URLs from the “www3.” subdomain of Forbes to DSPs.

SSP Inventory and Supply Policies

Many SSPs that transact ads on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain appear to have public, written policies that prohibit or discourage certain publisher ad serving practices, such as mis-declaring page URL information, excessively refreshing ad slots, or having a large amount of readers visit the publishers’ content through non-organic traffic sources.

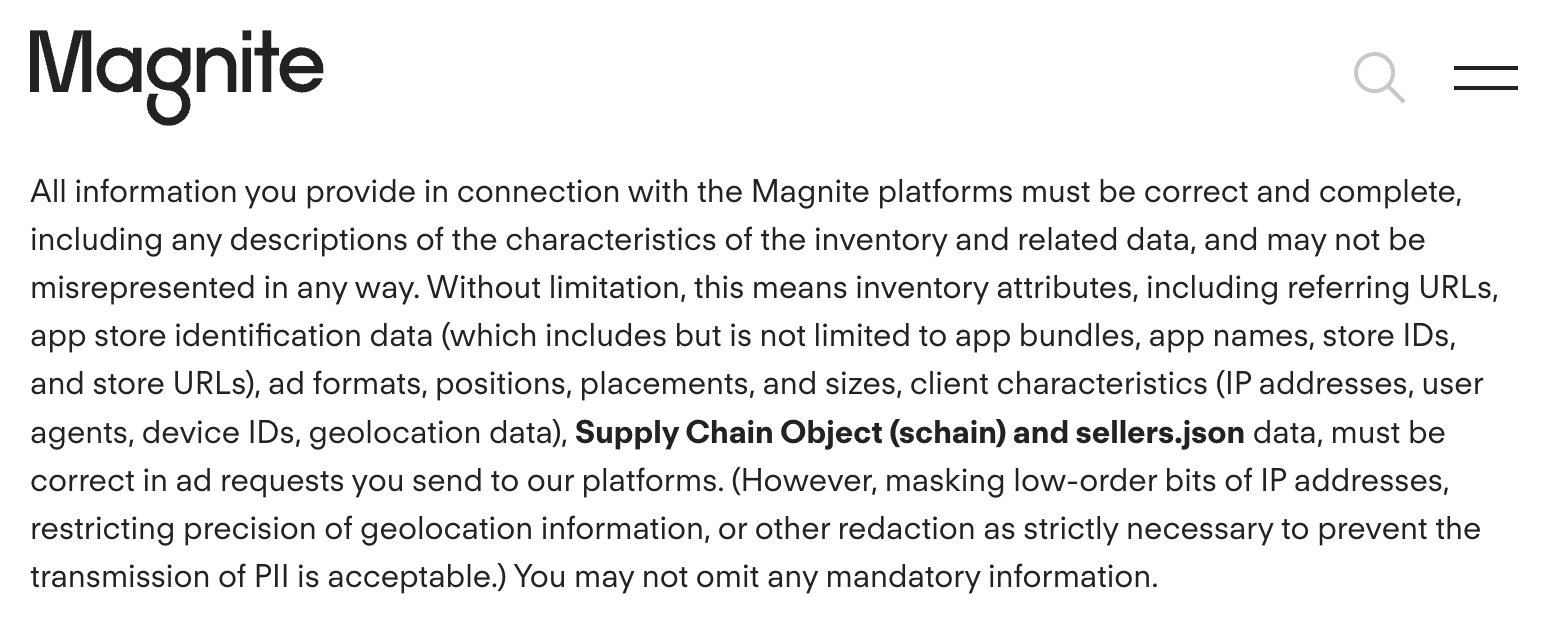

For example, Magnite’s “Inventory Quality Guidelines” for publishers state that: “All information you provide in connection with the Magnite platforms must be correct and complete, including any descriptions of the characteristics of the inventory and related data, and may not be misrepresented in any way. Without limitation, this means inventory attributes, including referring URLs, app store identification data (which includes but is not limited to app bundles, app names, store IDs, and store URLs)”

Screenshot of Magnite’s “Inventory Quality Guidelines” for publishers

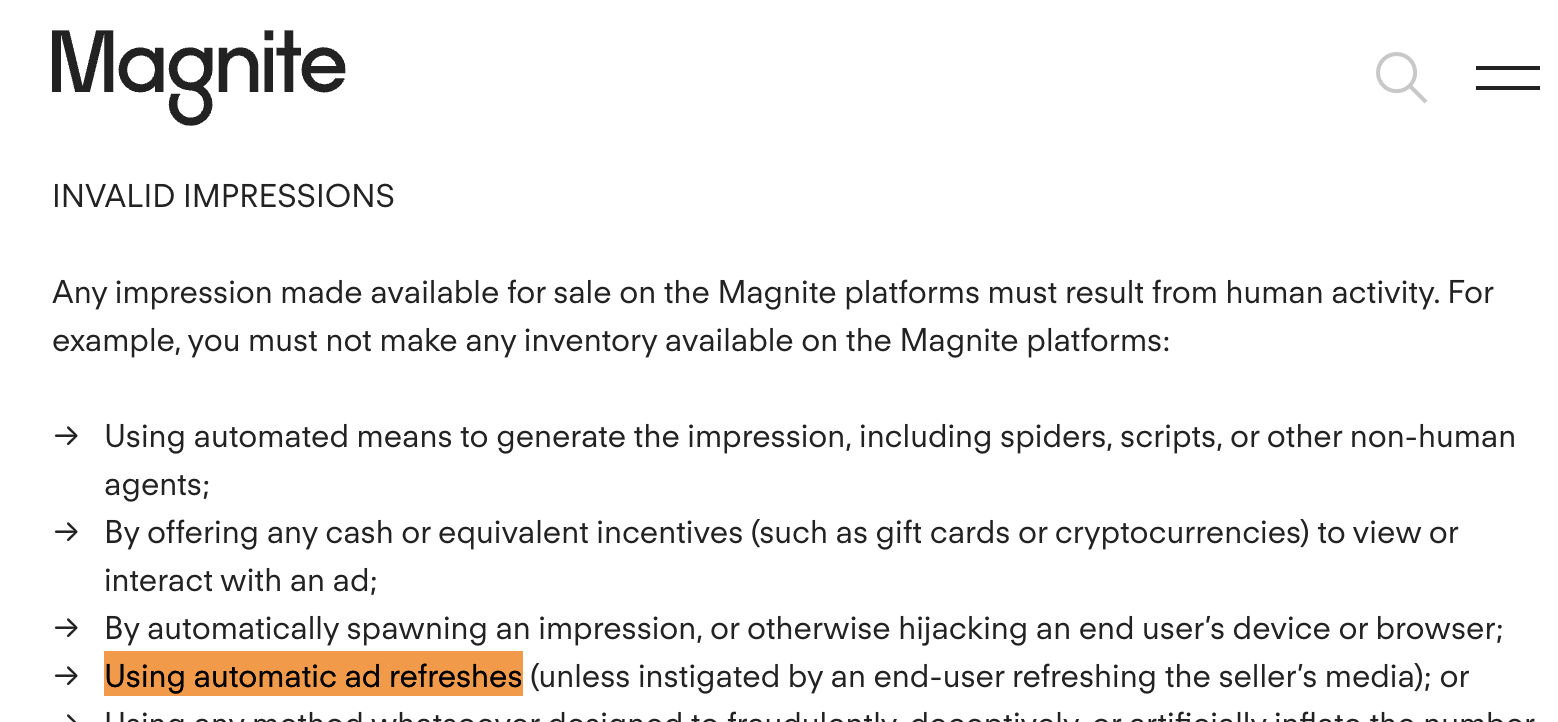

Furthermore, Magnite’s “Inventory Quality Guidelines” for publishers includes “Using automatic ad refreshes (unless instigated by an end-user refreshing the seller’s media)” as a form of “invalid impressions”.

Screenshot of Magnite’s “Inventory Quality Guidelines” for publishers

TripleLift SSP’s “Exchange Supply Policies” state that publishers “must acquire traffic primarily from organic sources”.

Screenshot of TripleLift’s “Exchange Supply Policies” for publishers

Pubmatic SSP’s “Supply Policy” states that publisher properties “demonstrate signs of user engagement. PubMatic cannot serve digital ads onto Publisher Properties that: [...] Demonstrate no evidence of a loyal, engaged audience; Appear designed primarily to display ads.”

Screenshot of Pubmatic’s “Supply Policy”

Furthermore, Pubmatic SSP’s “Supply Policy” for slideshow pages states that “Each slideshow page may contain a maximum of three ads [...] Auto-refresh is not permitted on slideshow pages.”

Screenshot of Pubmatic’s “Supply Policy”

Furthermore, Pubmatic SSP’s “Supply Policy” “basic guidelines” state that “The Publisher may not mask or cloak a Publisher Property’s URL or employ any other means to obscure the true source of traffic [...] The Publisher Inventory specifications and criteria provided by Publisher to PubMatic must be true and accurate.”

Screenshot of Pubmatic’s “Supply Policy”

Pubmatic’s “Supply Policy” also states “The Publisher Property may not contain an excessive number or density of ads. For most pages, no more than 3 ads in view at the same time is appropriate, and any additional ads may constitute “ad clutter.””

Screenshot of Pubmatic’s “Supply Policy”

Lastly, Pubmatic’s “Supply Policy” states that “In no event may a Publisher refresh an ad unit more than 20 times per end user session (e.g. slideshows).”

Screenshot of Pubmatic’s “Supply Policy”

Sharethrough “Ad Exchange Supply Policy” states that:

“Traffic from Sites should come from a balance of different sources, with an emphasis on direct traffic;”

“Sites must have suitable content to ad slot ratio per page. As a reference, ads should not take up more than 30% of a website;”

“Ad refresh timeouts should be set to 30 seconds or higher and only refresh when the ad unit is in view. Partner must keep the number, layout or refresh rate on a page the same no matter where the visitor to the Site originates.”

“Partner shall not mask or cloak a Site’s URL or employ other means to obscure the true source of traffic;”

Media.net’s “Inventory Policies” state that:

“All account information and details provided by each Publisher must be correct and complete, including any descriptions of the characteristics of the inventory and related data, and may not be misrepresented in any way.”

“Site Structure: Sites must have original content filled, navigation-friendly site design without excessive advertising. Sites pertaining to the following shall not be approved: Lack original content (e.g., copied stories, content without appropriate authorship or written by fictional authors, boilerplate information, syndicated content without attribution); Have mostly ads with little content or are sites developed primarily for advertising;”

“Invalid Traffic: The Publisher must acquire traffic primarily from organic sources [...] If a Publisher and/or Site has more than an acceptable threshold of purchased/acquired traffic or in the event that Media.net’s fraud monitoring tools indicate such behavior that is not commensurate to industry standards Media.net reserves the right to suspend or terminate such Publisher and or Site until resolved.”

“All attributes pertaining to your sites, including referring URLs [...] must be correct in ad requests you send to Media.net’s platforms.”

“Publishers shall not: [...] Stack ads in a manner that places advertisements on top of one another [...] Make modifications or in any way block visitor IP, referrer or page URL from being provided to Media.net”

Screenshot of Media.net’s “Inventory Policies”

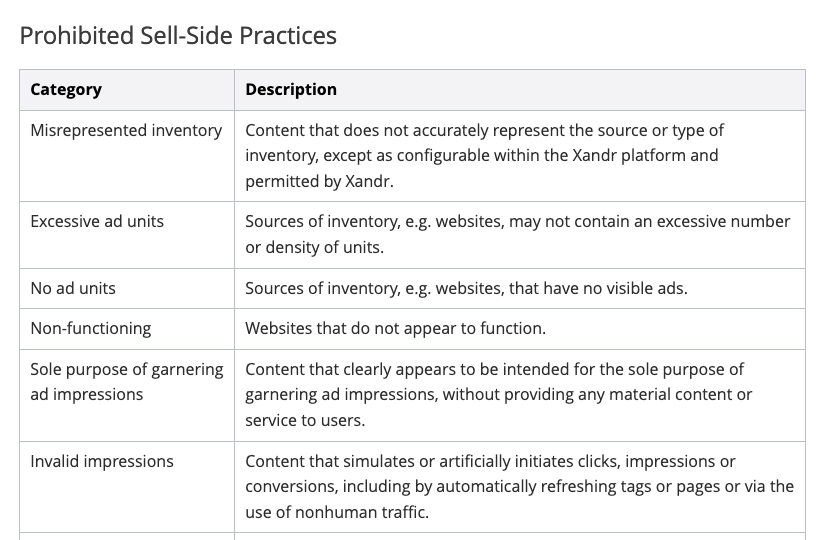

Xandr’s “Policies for Selling - Prohibited Sell-Side Practices” includes prohibitions against “Misrepresented inventory”, “excessive ad units”, and “automatically refreshing tags”

Screenshot of Xandr’s “Policies for Selling - Prohibited Sell-Side Practices”

As mentioned earlier, the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of forbes.com appears to source audience traffic from primarily paid sources (Taboola, Outbrain, Facebook ads, etc), appears to serve a relatively large number of ads and refresh ad units on slideshows, appears to “hide” specific page URLs from Google and Bing search engines, and appears to transact mis-declared page URLs in ad auctions via Media.net Prebid server.

It is unclear whether these practices on “www3.forbes.com” are consistent with various SSPs written policies, and whether or not SSPs are enforcing their own policies.

Results: Demand side platforms and bidders observed transacting ads on “www3.forbes.com”

Multiple demand side platforms (DSPs), bidders, and ad buying platforms were observed transacting ads on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain. Some of the DSPs were observed transacting mis-declared “www3.” subdomain inventory.

The Trade Desk DSP

Walmart DSP (built on Trade Desk DSP)

Acuity Ads / illumin

Yahoo DSP

AdTheorent DSP

Microsoft Xandr DSP

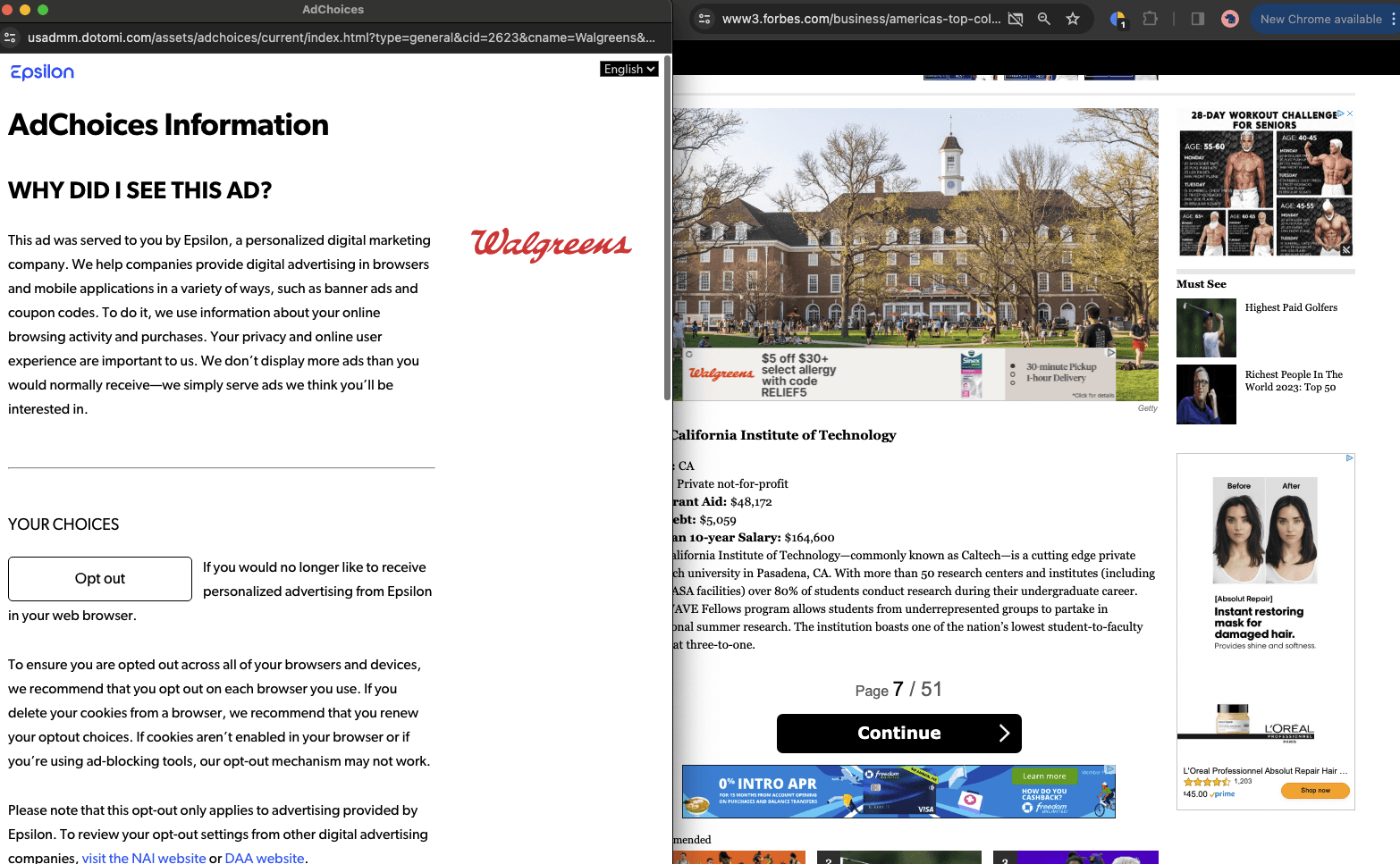

Publicis owned Epsilon Conversant

Google DV360 DSP

Amobee DSP

Amazon DSP

Zeta Global DSP

Adobe DSP

Criteo DSP

Beeswax DSP

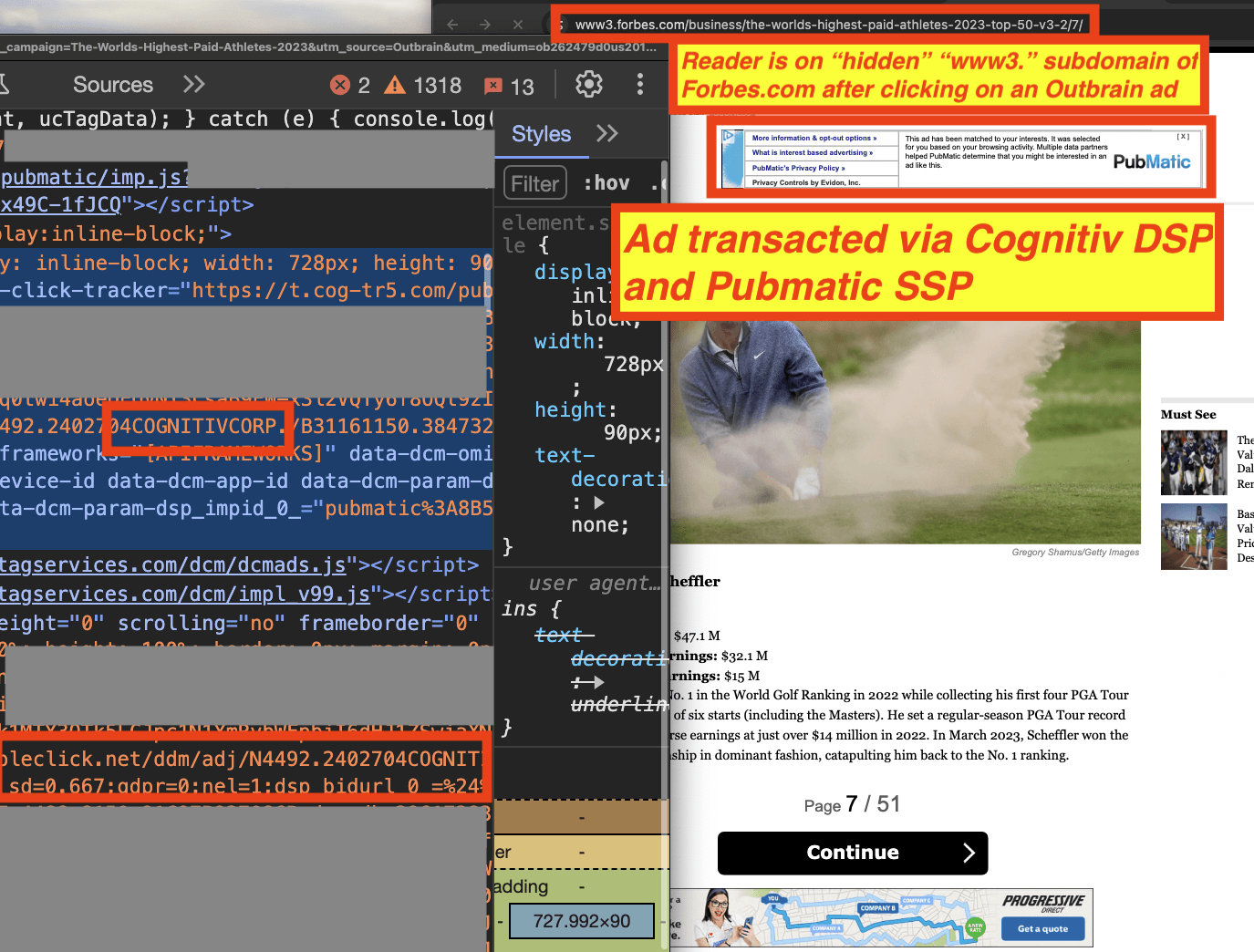

Cognitiv DSP

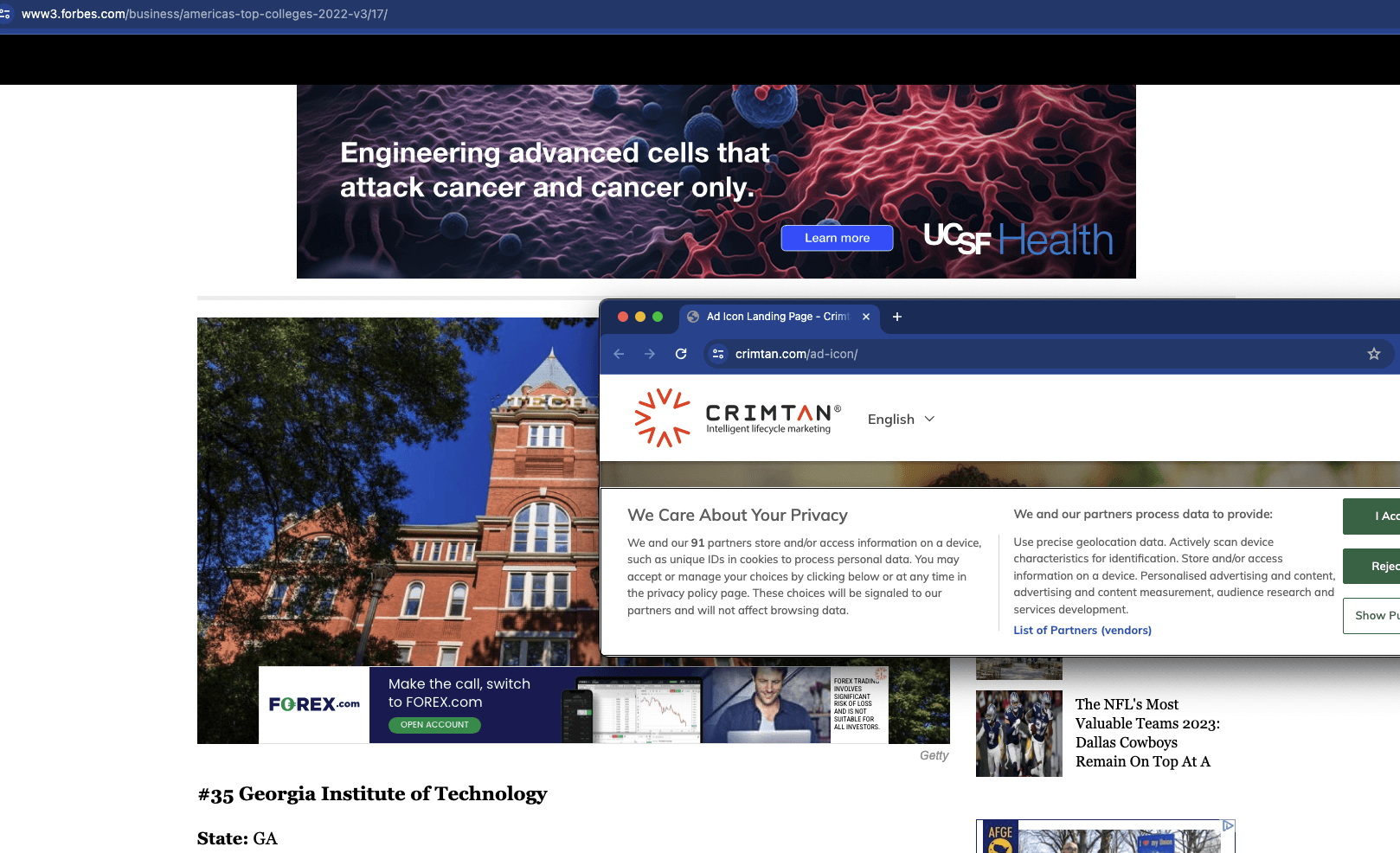

Crimtan DSP

Roku OneView DSP

Quantcast DSP

Centro Basis DSP

Screenshot showing a Walmart DSP ad serving an ad for Unilever on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain. The page URL appears to have been mis-declared to Walmart DSP.

Many of the aforementioned DSPs have received the TAG Certified Against Fraud seal, and/or have policies against mis-declaration of page data. Some have policies that prohibit “Made for Advertising” related ad serving practices.

For example, The Trade Desk Inventory Policies state: “Ad Load - Ad refresh must be limited to intervals of 30 seconds or more and must occur only while in-view. Excessive or non-viewable refreshed ads will result in the site or seller being blocked.” The Policies also state: “Be sure to include valid and accurate values in the following fields (or for non-OpenRTB integrations, any equivalent signifier): [...] site.page with the full-page URL that includes a query string, key-value pairs, and UTM parameters.”

Screenshot of The Trade Desk Inventory Policies

Trade Desk Inventory Policies also state: “Traffic Source - To transact on The Trade Desk platform, be sure to meet the following traffic source requirements and policies: [...] Inventory that appears to result from synthetic or purchased traffic (for example, incentivized, rewarded web views, or clickbait style advertising) is subject to restriction.”

Lastly, Trade Desk Inventory Policies state: “Only one source of inventory for a particular media type per seller is allowed. For example, do not send display inventory via multiple integration types or header bidding solutions (OB, TAM, Prebid).”

Screenshot showing source code of a Bayer ad on “www3.” subdomain of Forbes. The source code of the ad shows it was transacted via Trade Desk DSP and Magnite SSP. The ad source code suggests that the page URL was mis-declared to Trade Desk’s bidder as “www.forbes.com”, when in reality the user was on the “www3.” subdomain of Forbes.

Screenshot of a Keystone Ski Resort ad, transacted via Adobe DSP

Screenshot of an ad transacted via Cognitiv DSP and Pubmatic SSP

Screenshot of three ads transacted via AdTheorent DSP

Screenshot of an ad transacted via Crimtan DSP on the “www3.forbes.com” subdomain

Screenshot of a Walgreen ad transacted via Publicis owned Epsilon Conversant on the “www3.forbes.com” subdomain

Screenshot of a Paramount+ ad transacted via Yahoo DSP on the “www3.forbes.com” subdomain

Screenshot of a Unilever Dove ad transacted via Amazon DPS on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of forbes.com

Results: Verification & monitoring vendors observed within the source code of ads served on “www3.forbes.com”

In May 2022, the Wall Street Journal published an article titled: “Ad-Tech Firms Didn’t Sound Alarm on False Information in Gannett’s Ad Auctions”, with the subtitle: “Firms that facilitate online-ad transactions had enough information to detect error that affected Gannett’s systems for over nine months”.

Prior analyses showed that the owner of USA Today - Gannett Media - had been submitting mis-declared page and domain data to ad auctions for nine months. The issue was not fully disclosed until a WSJ published an article on the matter in March 2022.

Screenshot of a 2022 Wall Street Journal article titled: “Ad-Tech Firms Didn’t Sound Alarm on False Information in Gannett’s Ad Auctions”

The WSJ reported: “Gannett pays Integral Ad Science for insights on its traffic and metrics related to its advertising, according to a Gannett spokeswoman. Data gathered by the researchers and reviewed by the Journal showed that Integral Ad Science received information revealing the Gannett discrepancy thousands of times [...] Integral Ad Science didn’t inform Gannett of the phenomenon, the Gannett spokeswoman said, and didn’t inform its advertiser clients, according to media buyers.”

Screenshot of a 2022 Wall Street Journal article titled: “Ad-Tech Firms Didn’t Sound Alarm on False Information in Gannett’s Ad Auctions”

The WSJ further reported: “A Human Security representative said the company’s monitoring system picked up on the discrepancy but didn’t flag it as fraudulent, so Human didn’t notify clients. Moat declined to comment.”

The Media Rating Council (MRC), a US-based nonprofit that manages accreditation for media research and rating purposes, defines “Domain and App misrepresentation”, including “falsified domain / site location”, as a form of Sophisticated Invalid Traffic (SIVT).

Trustworthy Accountability Group (TAG) “Certified Against Fraud” Guidelines specifically state that: “To achieve the Certified Against Fraud Seal, any participating company must ensure that 100% of the monetizable transactions (including impressions, clicks, conversions, etc.) that it handles are filtered for both general invalid traffic (GIVT) and sophisticated invalid traffic (SIVT) in a manner compliant with a TAG-recognized standard for IVT detection and removal as referenced in Appendix A.”

Several vendors who are MRC accredited for “Sophisticated Invalid Traffic Detection/Filtration” were observed receiving telemetry that could have potentially alerted them to the “www3.” Forbes page URL mis-declarations.

These include:

Integral Ad Science (IAS)

DoubleVerify

Oracle Moat

HUMAN Security (fka White Ops)

Three of these four SIVT detection vendors appear to have direct partnerships with Forbes, as evidenced by the deployment of their respective publisher-specific Javascript tools directly on the source code of the “normal” “www.forbes.com” website. In the screenshot below, one can observe Chrome Developer Tools’ “Network” tab opened on the “normal” “www.forbes.com” website. The “Network” tab shows that the “normal” “www.forbes.com” website loads publisher Javascript code from three ad verification vendors:

Oracle Moat - https://z.moatads.com/forbesprebidheader122641196143/moatheader.js

IAS - https://cdn.adsafeprotected.com/iasPET.1.js

DoubleVerify - https://pub.doubleverify.com/dvtag/30290112/DV1110994/pub.js

To be clear, this is code that is loaded directly from the main page frame and Document Object Model (DOM) of “www.forbes.com”; the code is not being loaded or initiated from within an ad iframe. These are apparently the publisher suite Javascript tools of the verification vendors; they should not be confused with the advertiser (“buy side”) ad verification tools provided to media buyers. The advertiser Javascript code loads within ad iframes.

Screenshot of the “normal” “www.forbes.com” website, showing the publisher specific Javascript code from Oracle Moat, IAS, and DoubleVerify is installed by the publisher on its webpages. This code was not observed on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of Forbes.

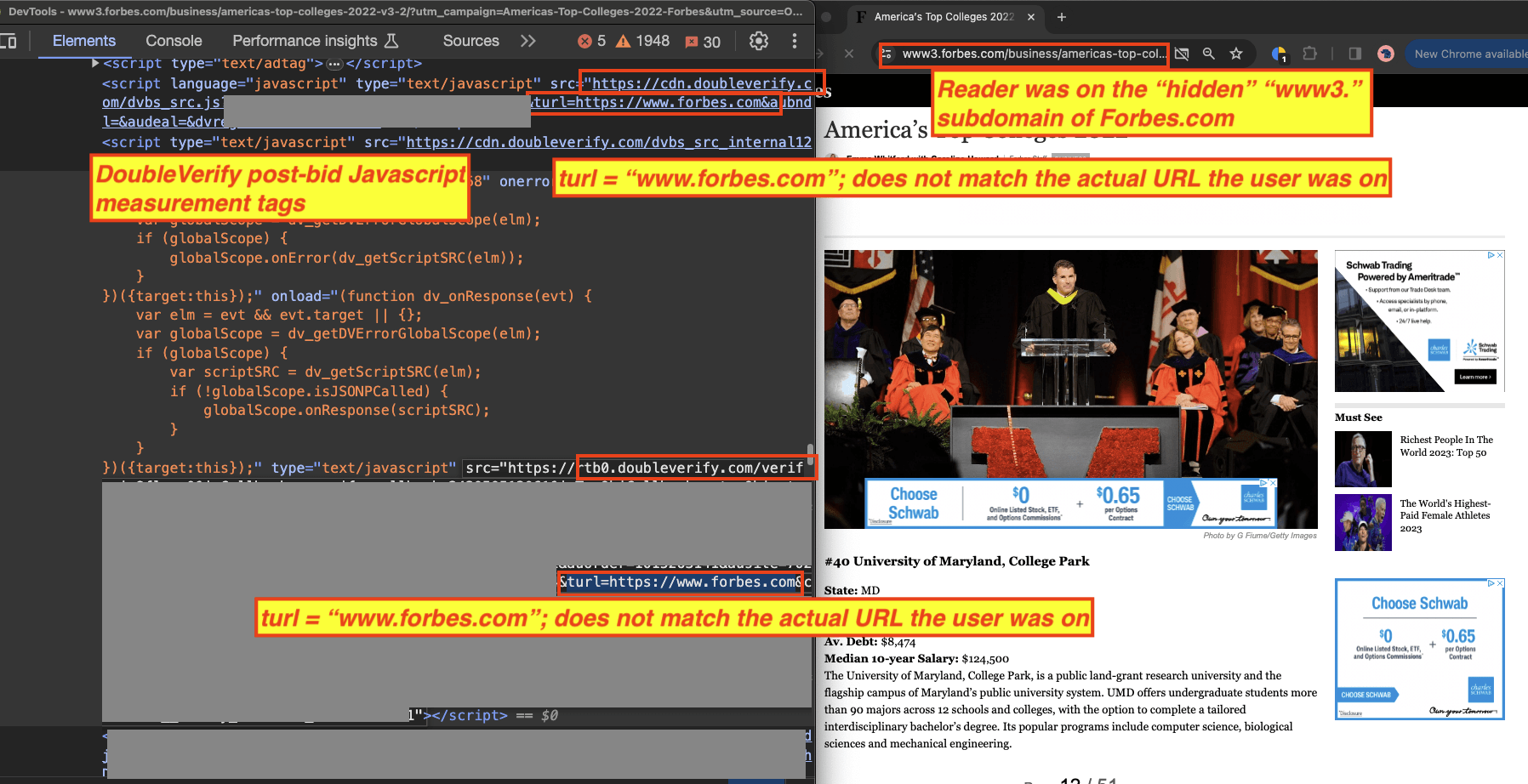

Forbes does not appear to deploy these three verification vendors’ publisher tools directly on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of forbes.com. However, many brands’ ads, when loaded inside of iframes on “www3.forbes.com”, appeared to load Javascript tags or image pixels from IAS, DV, Oracle Moat, and/or HUMAN Security. These tags appear to have records of what page URLs were declared in ad auction requests, verses on what page URLs the ads actually served post-auction.

Screenshot showing IAS’s post-bid pixel loading within an ad creative. The “bidurl” appears to be set to “www.forbes.com”, wherein the reader was actually on “www3.forbes.com”

Screenshot showing Oracle Moat’s post-bid pixel loading within an ad creative. The “bd” and “zMoatOrigSlicer1” query string parameters appear to be set “www.forbes.com”, wherein the reader was actually on “www3.forbes.com”

Screenshot showing Oracle Moat’s post-bid pixel loading within an ad creative. The “turl” query string parameters appear to be set to “www.forbes.com”, wherein the reader was actually on “www3.forbes.com”

Furthermore, several of the ad tech vendors observed transacting mis-declared ad inventory from “www3.forbes.com” appear to partner with HUMAN Security and other vendors. PubMatic “uses a powerful combination of IAS and White Ops to monitor invalid traffic rates.” TripleLift states: “Every ad is pre-scanned by WhiteOps for fraud before brands have an opportunity to bid on it. If WhiteOps tells us that they believe that an ad opportunity stems from a bad actor, we don’t hold an auction.” HUMAN’s website lists Xandr and The Trade Desk as customers.

Screenshot showing Human Security’s post-bid measurement javascript tag loading within an ad creative. The “di” parameter was mis-declared to be “www.forbes.com”, wherein the reader was actually on “www3.forbes.com”

This study does not assert whether any of these verification or monitoring vendors did or did not detect the page URL mis-declaration of “www3.forbes.com” ad inventory transacted by Media.net Prebid Server and the four SSPs (TripleLift, Microsoft Xandr, Pubmatic, and Magnite). This study does not assert whether or not the vendors labeled or filtered the mis-declared page URLs. This study does not assert whether or not the ad tech vendors notified their media buyer or publisher (in the case of Forbes) publisher clients of the apparent page URL mis-declaration.

Results: potential direct sold insertion orders observed on “www3.forbes.com”

Some of the ads observed serving on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain may not have been transacted via programmatic open auction. Some of the ads observed in this environment may have been transacted through special, negotiated arrangements between media buyers and Forbes’ ad sales team. These could include potential direct-sold insertion orders, wherein a media buyer may have worked with Forbes’ ad sales team to negotiate a specific rate and package for ad delivery on Forbes’ digital website.

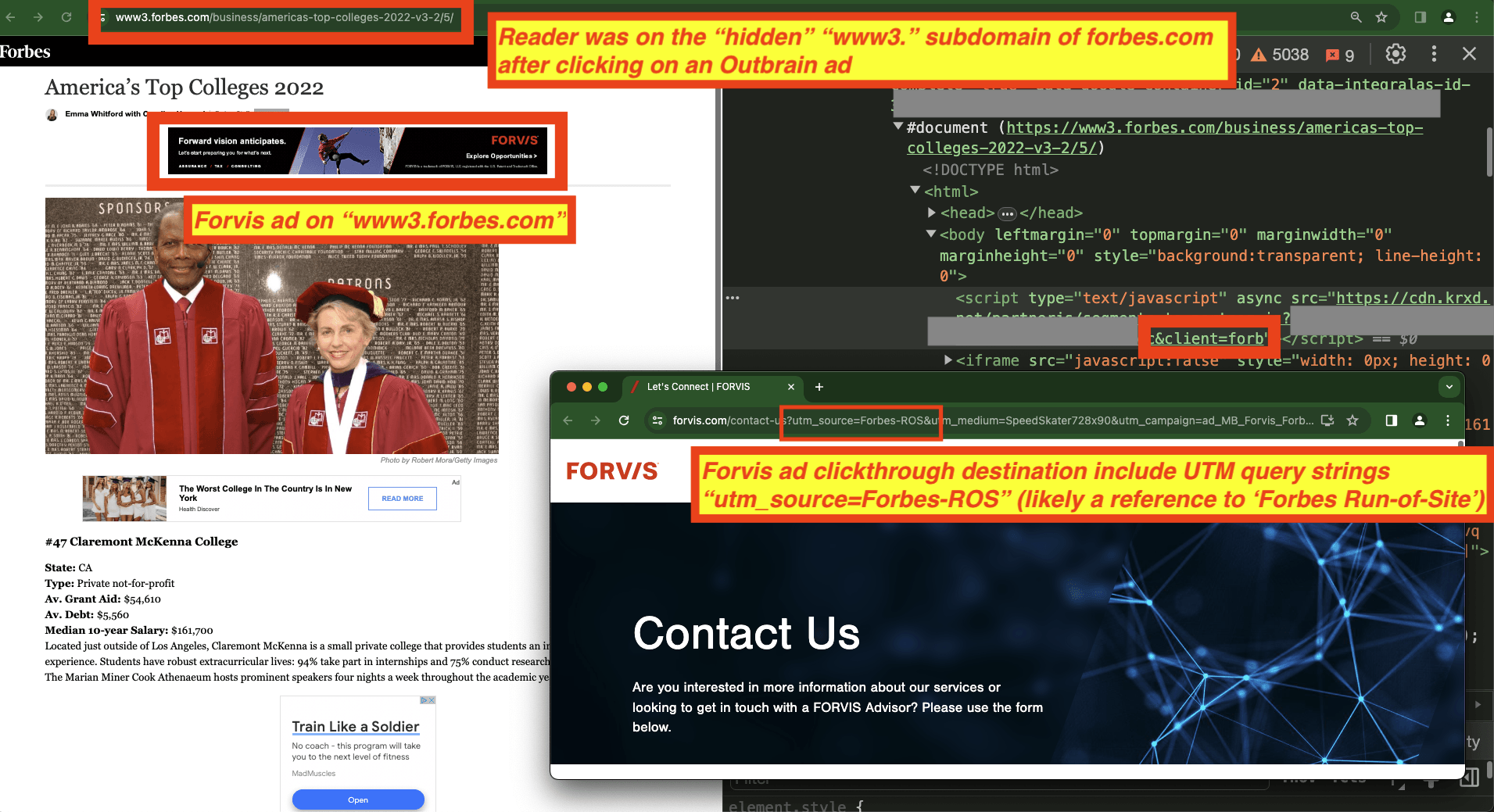

Some of the ads seen on “www3.forbes.com” were observed to include CM360 ad server pixels from Forbes. Furthermore, for some of these ads, the ad clickthrough destination URLs include UTM query string parameters with various high entropy strings that appear to have been set up by ad operations and trafficking specialists to potentially denote ad buys that were customized to Forbes.

In the screenshot below, one can observe an ad for Forvis, LLP a top 10 US public accounting firm which provides assurance, tax, and consulting services. The Forvis ad was observed being served multiple times to a reader on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain, auto-refreshing as the consumer navigated the slides of the “America’s Top Colleges 2022” slideshow. The ad clickthrough URL for the Forvis ad includes the UTM query string parameter: “utm_source” = “Forbes-ROS”. “ROS” is a commonly used abbreviation in ad ops for “Run of Site”. The presence of this query parameter suggests that the Forvis ad was being delivered through some kind of directly negotiated and customized deal between Forvis the advertiser and Forbes the publisher. It is unclear as to whether Forvis was aware that this ad was being served many times over to individual readers on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of Forbes.

Screenshot of a Forvis ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain after the reader clicked on an Outbrain ad to arrive on the page. The ad’s clickthrough URL includes UTM query string parameters that reference “Forbes-ROS”, which may be a label for “Forbes Run of Site”.

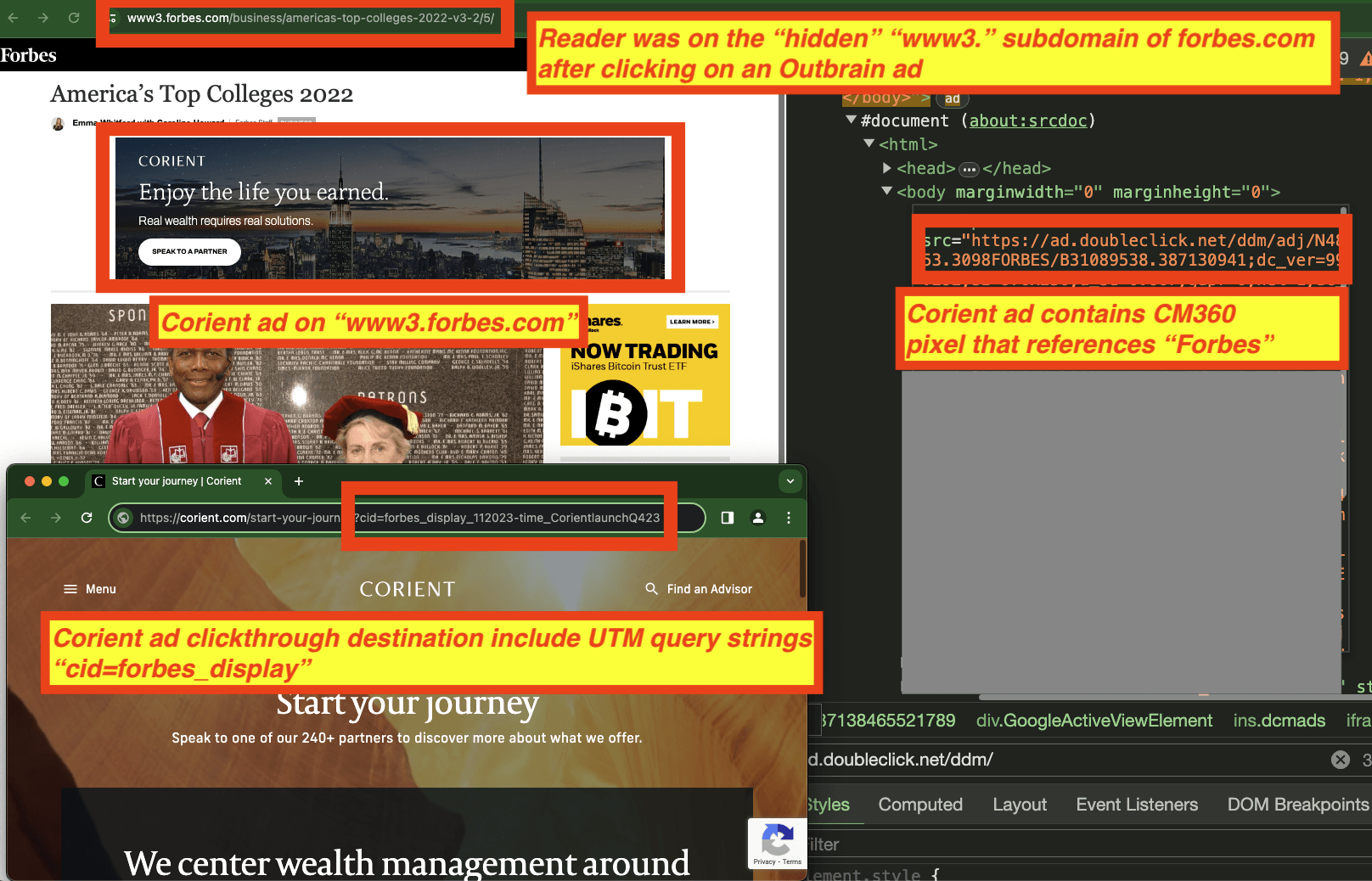

As a second example, one can observe an ad for Corient, a financial services provider that offers wealth management and family office solutions. The Corient ad was observed being served multiple times to a reader on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain, auto-refreshing as the consumer navigated the slides of the “America’s Top Colleges 2022” slideshow.

The ad source code includes CM360 ad server pixels that appear to reference “Forbes” directly, which may suggest that Forbes’ CM360 account was used to traffic the ad.

The ad clickthrough URL for the Corient ad includes the UTM query string parameter: “cid” = “forbes-display”. The presence of this query parameter suggests that the Corient ad may have been delivered through some kind of directly negotiated and customized deal between Corient the advertiser and Forbes the publisher. It is unclear as to whether Corient was aware that this ad was being served many times over to individual readers on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of Forbes.

Screenshot of a Corient ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain after the reader clicked on an Outbrain ad to arrive on the page. The ad’s clickthrough URL includes UTM query string parameters that reference “forbes_display”, and the ad’s source code includes a CM360 pixel which may have originated from Forbes’ own CM360 ad server account.

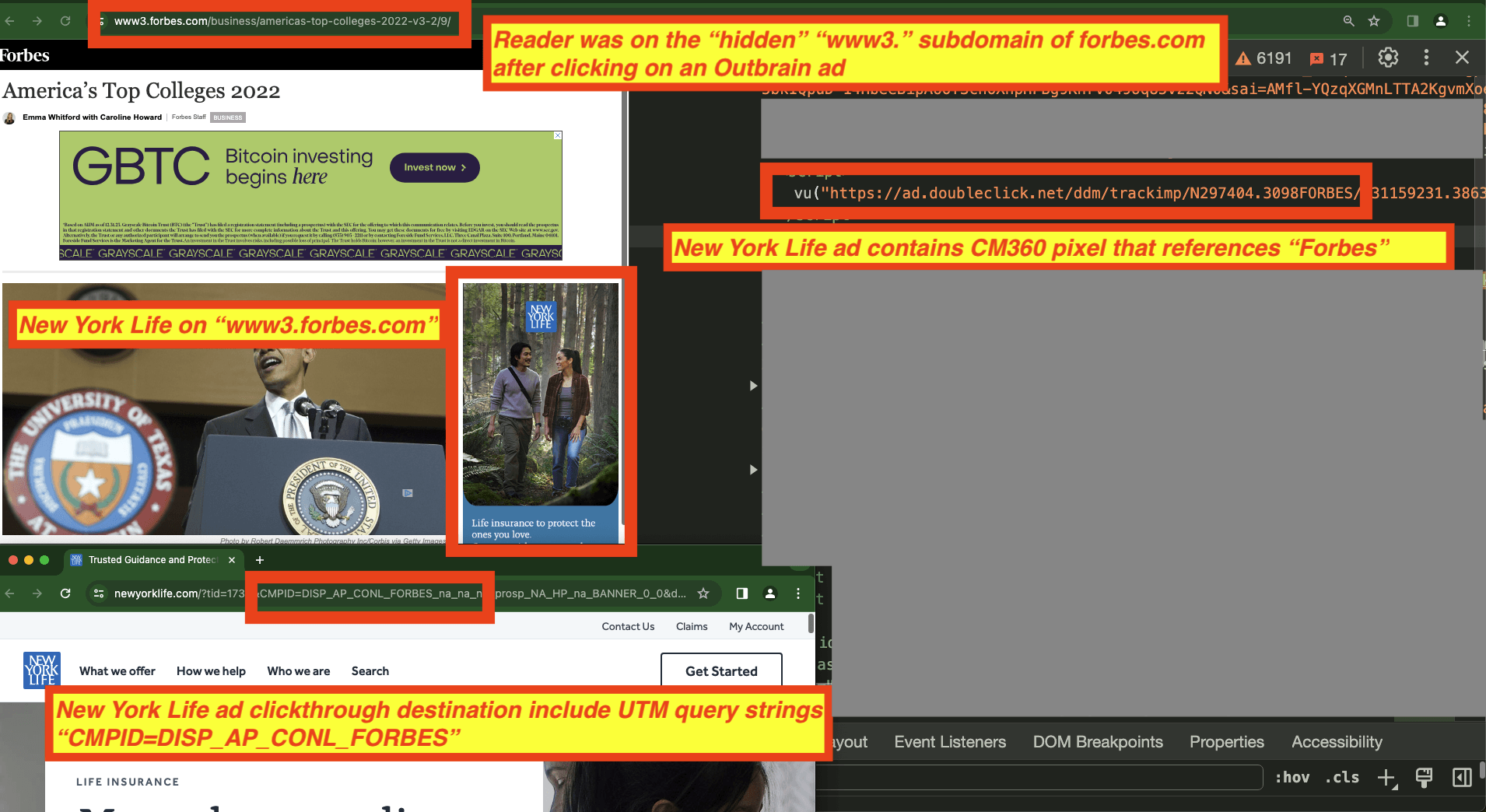

As a third example, one can observe an ad for New York Life Insurance Company, the third-largest life insurance company and largest mutual life insurance company in the United States. The New York Life Insurance ad was observed being served multiple times to a reader on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain, auto-refreshing as the consumer navigated the slides of the “America’s Top Colleges 2022” slideshow.

The ad source code includes CM360 ad server pixels that appear to reference “Forbes” directly, which may suggest that Forbes’ CM360 account was used to traffic the ad.

The ad clickthrough URL for the New York Life ad includes the UTM query string parameter: “CMPID” = “DISP_AP_CONL_FORBES”. The presence of this query parameter suggests that the New York Life Insurance ad may have been delivered through some kind of directly negotiated and customized deal between New York Life Insurance the advertiser and Forbes the publisher. It is unclear as to whether New York Life Insurance was aware that this ad was being served many times over to individual readers on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of Forbes.

Screenshot of a New York Life Insurance ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain after the reader clicked on an Outbrain ad to arrive on the page. The ad’s clickthrough URL includes UTM query string parameters that reference “CONL_FORBES”, and the ad’s source code includes a CM360 pixel which may have originated from Forbes’ own CM360 ad server account.

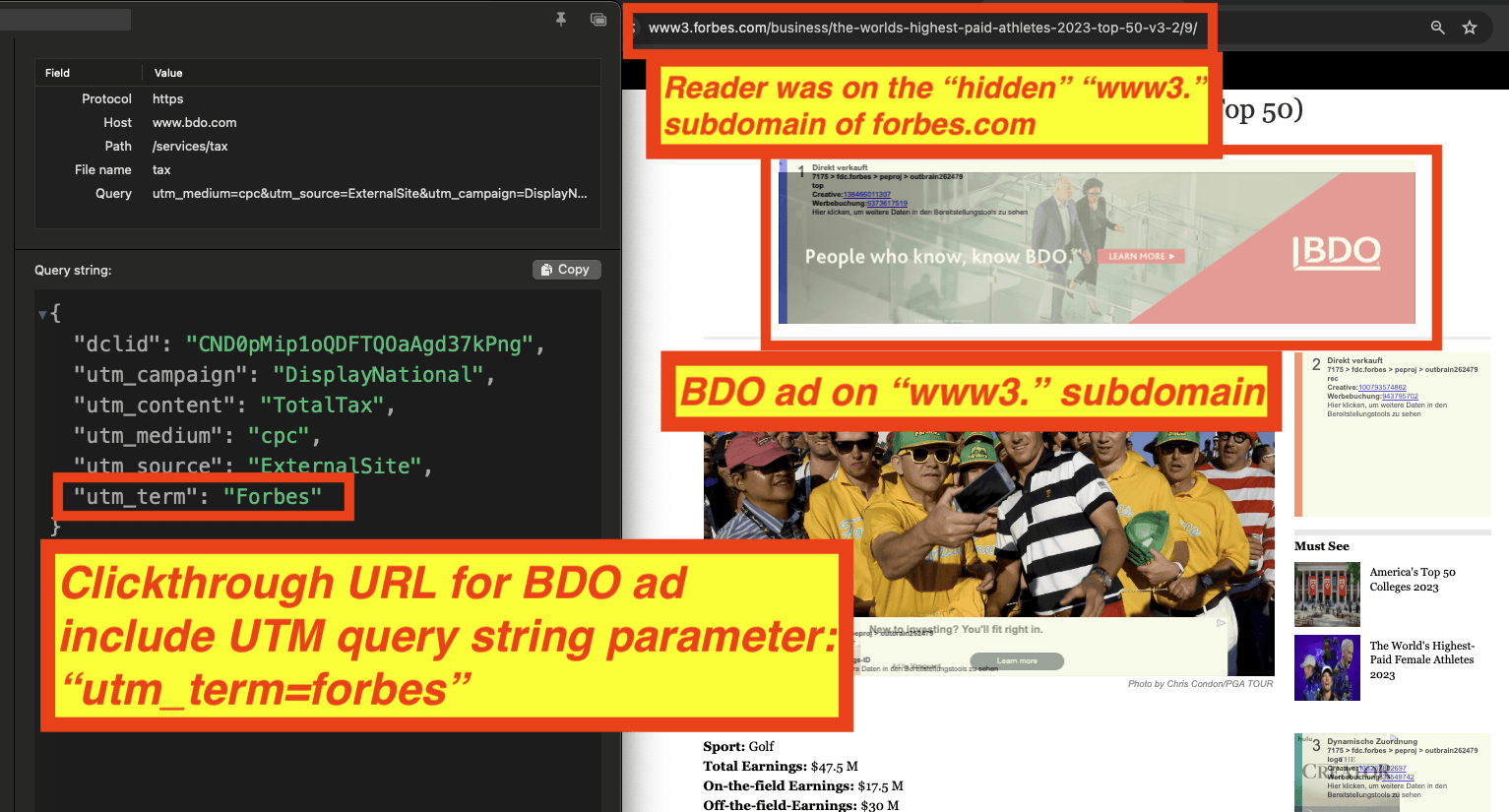

As a fourth example, one can observe an ad for BDO US, an assurance, tax, and financial advisory services. The BDO US ad was observed being served multiple times to a reader on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain, auto-refreshing as the consumer navigated the slides of the “America’s Top Colleges 2022” slideshow.

The ad clickthrough URL for the BDO US ad includes the UTM query string parameter: “utm_term” = “Forbes”. The presence of this query parameter suggests that the BDO ad may have been delivered through some kind of directly negotiated and customized deal between BDO the advertiser and Forbes the publisher. It is unclear as to whether BDO was aware that this ad was being served many times over to individual readers on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of Forbes.

Screenshot of a BDO ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain after the reader clicked on an Outbrain ad to arrive on the page. The ad’s clickthrough URL includes UTM query string parameters that reference “utm_term=forbes”.

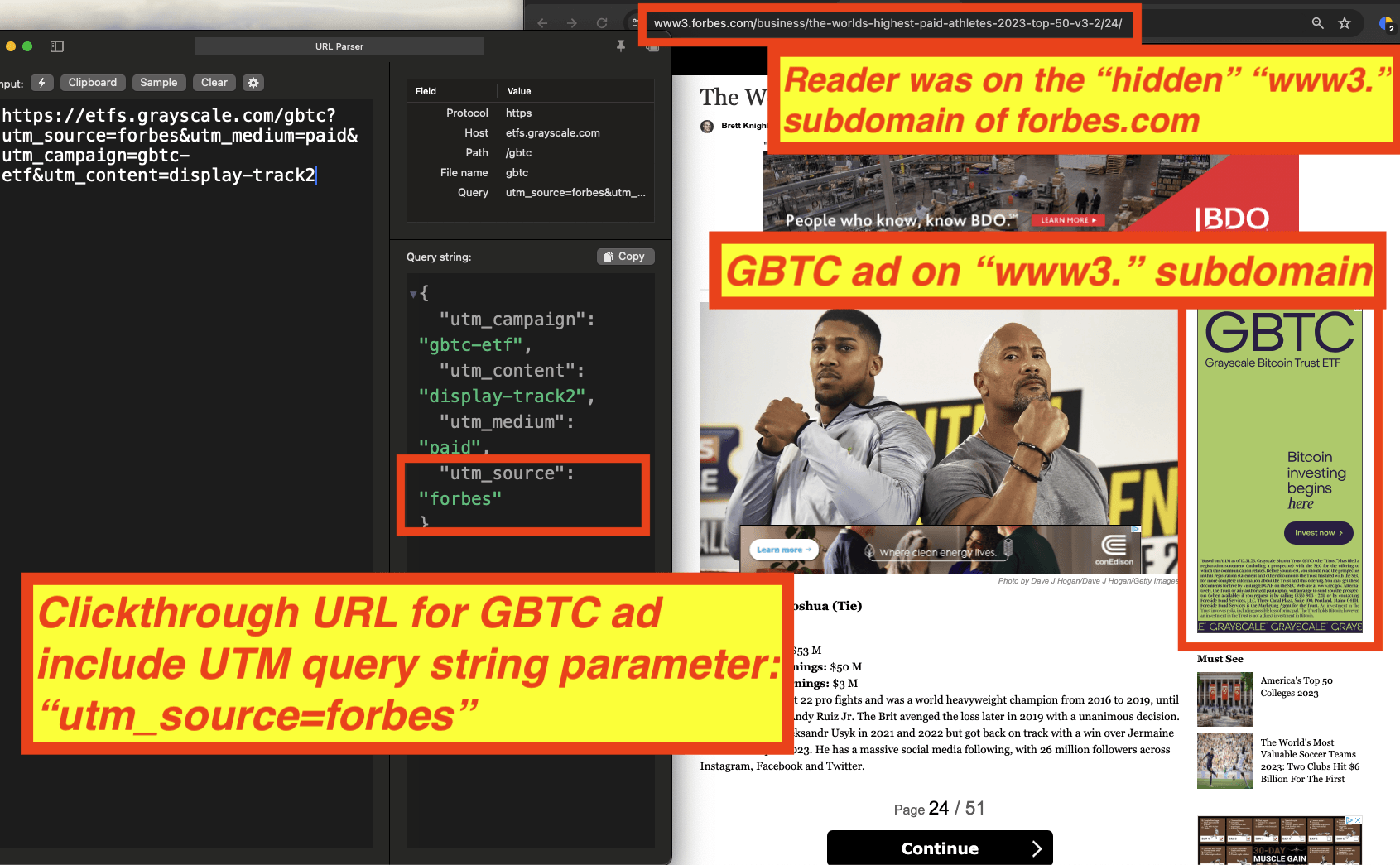

As a fifth example, one can observe an ad for Grayscale Bitcoin Trust ETF (GBTC). The GBTC ad was observed being served multiple times to a reader on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain, auto-refreshing as the consumer navigated a slideshow.

The ad clickthrough URL for the GBTC ad includes the UTM query string parameter: “utm_source” = “Forbes”. The presence of this query parameter suggests that the GBTC ad may have been delivered through some kind of directly negotiated and customized deal between GBTC the advertiser and Forbes the publisher. It is unclear as to whether GBTC was aware that this ad was being served many times over to individual readers on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of Forbes.

Screenshot of a Greyscale Bitcoin Trust ETF ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain after the reader clicked on an Outbrain ad to arrive on the page. The ad’s clickthrough URL includes UTM query string parameters that reference “utm_source=forbes”.

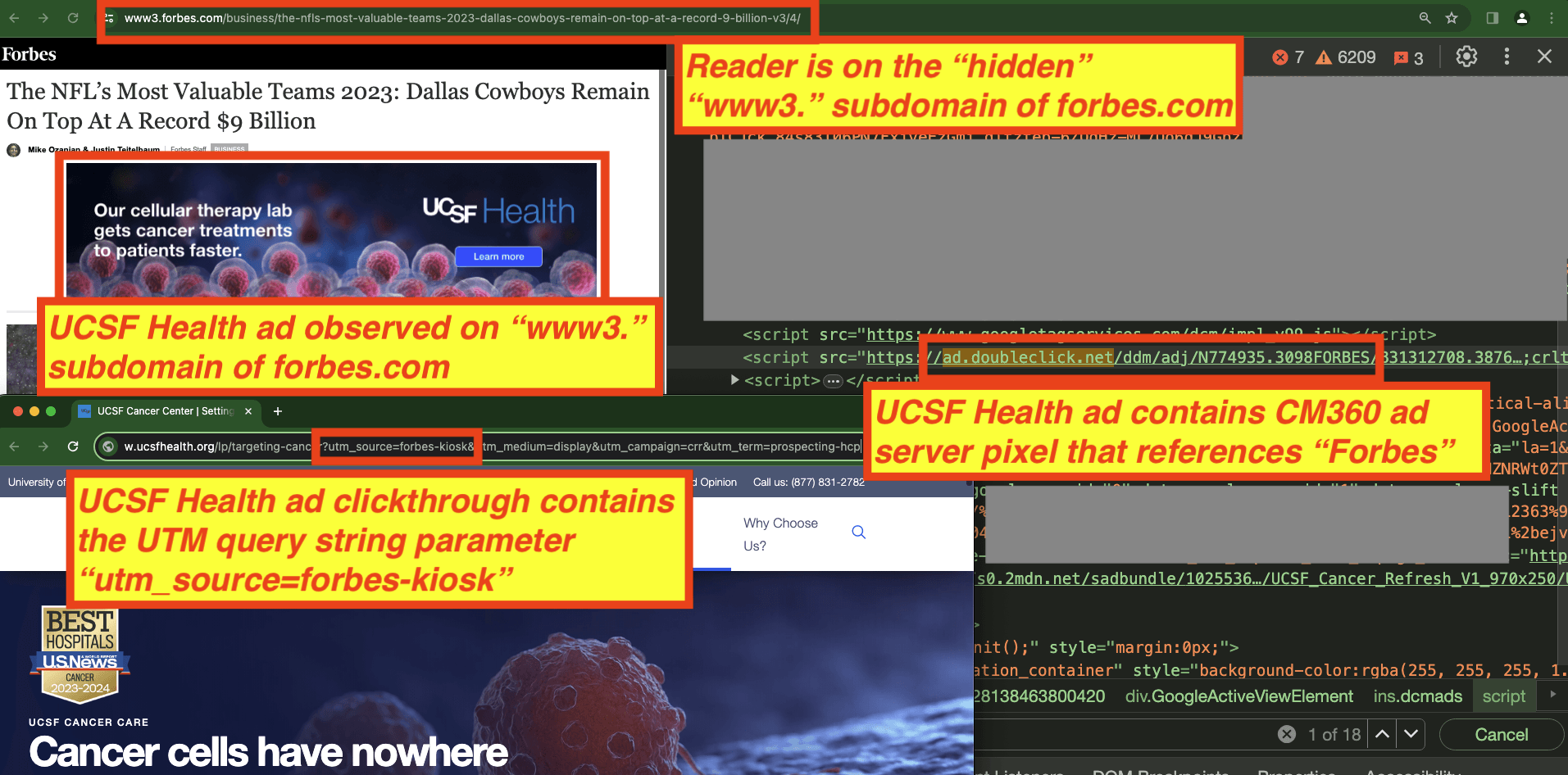

As a sixth example, one can observe an ad for University of California San Francisco Health Cancer Care (UCSF Health). The UCSF Health ad was observed being served multiple times to a reader on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain, auto-refreshing as the consumer navigated a slideshow.

The ad source code includes CM360 ad server pixels that appear to reference “Forbes” directly, which may suggest that Forbes’ CM360 account was used to traffic the ad.

The ad clickthrough URL for the UCSF Health ad includes the UTM query string parameter: “utm_source” = “forbes-kiosk”. The presence of this query parameter suggests that the UCSF Health ad may have been delivered through some kind of directly negotiated and customized deal between UCSF Health the advertiser and Forbes the publisher. It is unclear as to whether UCSF Health was aware that this ad was being served many times over to individual readers on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of Forbes.

Screenshot of a University of California San Francisco Health (UCSF Health) ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain after the reader clicked on an Outbrain ad to arrive on the page. The ad’s clickthrough URL includes UTM query string parameters that reference “utm_source=forbes-kios”, and the ad’s source code includes a CM360 pixel which may have originated from Forbes’ own CM360 ad server account.

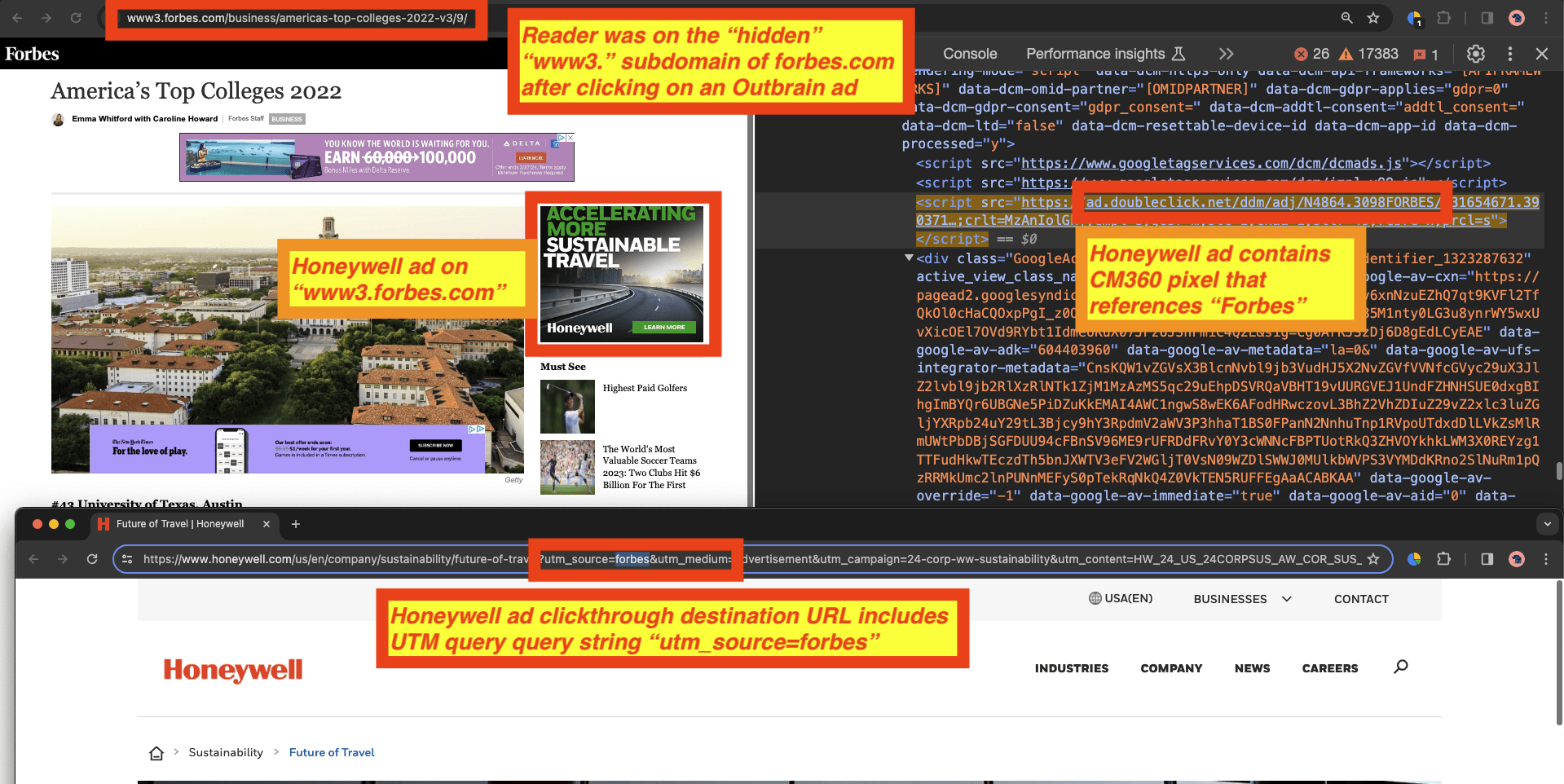

As a seventh example, one can observe an ad for Honeywell.

The ad source code includes CM360 ad server pixels that appear to reference “Forbes” directly, which may suggest that Forbes’ CM360 account was used to traffic the ad.

The ad clickthrough URL for the Honeywell ad includes the UTM query string parameter: “utm_source” = “forbes”. The presence of this query parameter suggests that the Honeywell ad may have been delivered through some kind of directly negotiated and customized deal between Honeywell the advertiser and Forbes the publisher. It is unclear as to whether Honeywell was aware that this ad was being served many times over to individual readers on the “hidden” “www3.” subdomain of Forbes.

Screenshot of a Honeywell ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain after the reader clicked on an Outbrain ad to arrive on the page. The ad’s clickthrough URL includes UTM query string parameters that reference “utm_source=forbes”, and the ad’s source code includes a CM360 pixel which may have originated from Forbes’ own CM360 ad server account.

As an eighth example, one can observe an ad for Microsoft Copilot. The ad source code includes CM360 ad server pixels that appear to reference “Forbes” directly, which may suggest that Forbes’ CM360 account was used to traffic the ad.

Screenshot of a Microsoft Copilot ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain after the reader clicked on an Outbrain ad to arrive on the page. The ad’s source code includes a CM360 pixel which may have originated from Forbes’ own CM360 ad server account.

While some of these client-side forensics observations are suggestive of these ads potentially having been placed or transacted via some kind of direct buy between an advertiser and Forbes, there could be false positives. For example, some of these ads could have been transacted through open auction programmatic channels. As such, readers should be careful and nuanced when interpreting the above observations. To fully confirm whether a given ad transacted via direct buy insertion order or some similar mechanism, one would need to either speak with the related advertiser or Forbes’ ad ops team.

Results: agencies observed transacting ads on www3.forbes.com

Multiple media agencies were observed potentially transacting ads on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain.

These appear to include:

Horizon Media

Goodway Group

IPG Kinesso (fka Cadreon or Matterkind)

Omnicom

Havas

MiQ

Dentsu

GroupM/WPP

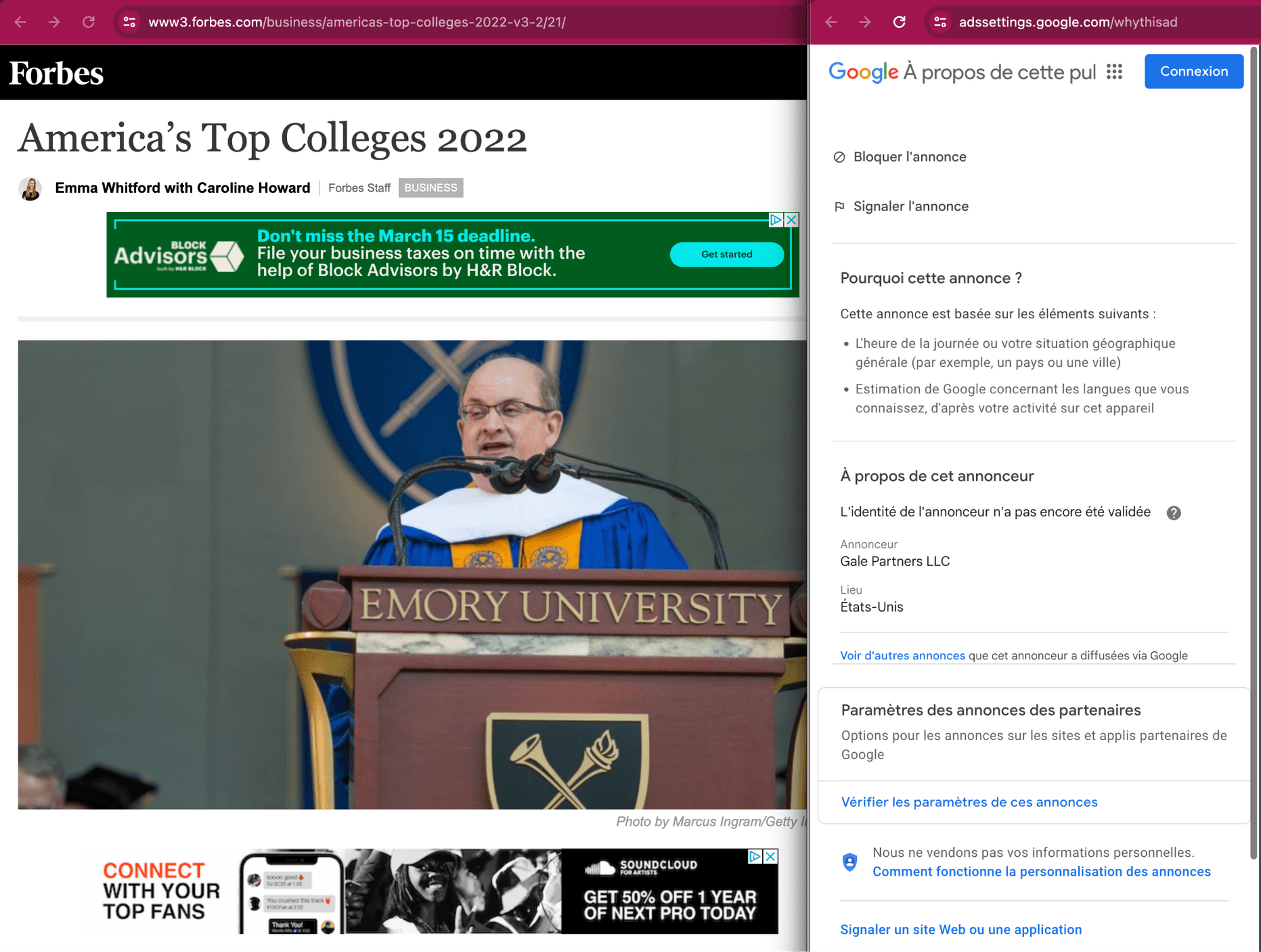

Gale Partners (part of Stagwell)

Publicis

Forward 3D

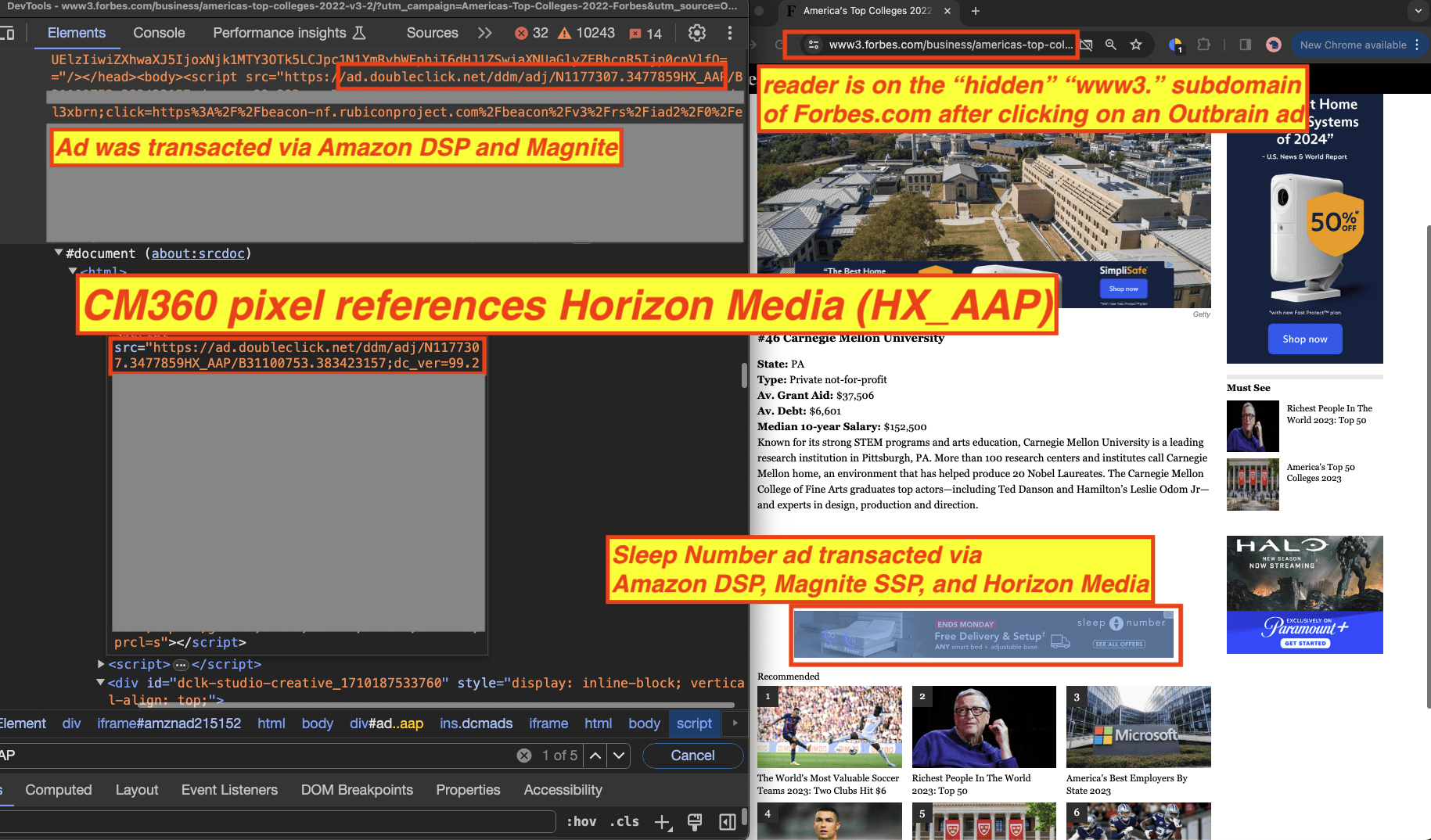

Screenshot of a Sleepnumber.com ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The ad source code includes a CM360 pixel that references “HX_AAP”.

Screenshot of a Safelite AutoGlass ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The “Why this ad?” info modal shows the ads were transacted by Horizon Media.

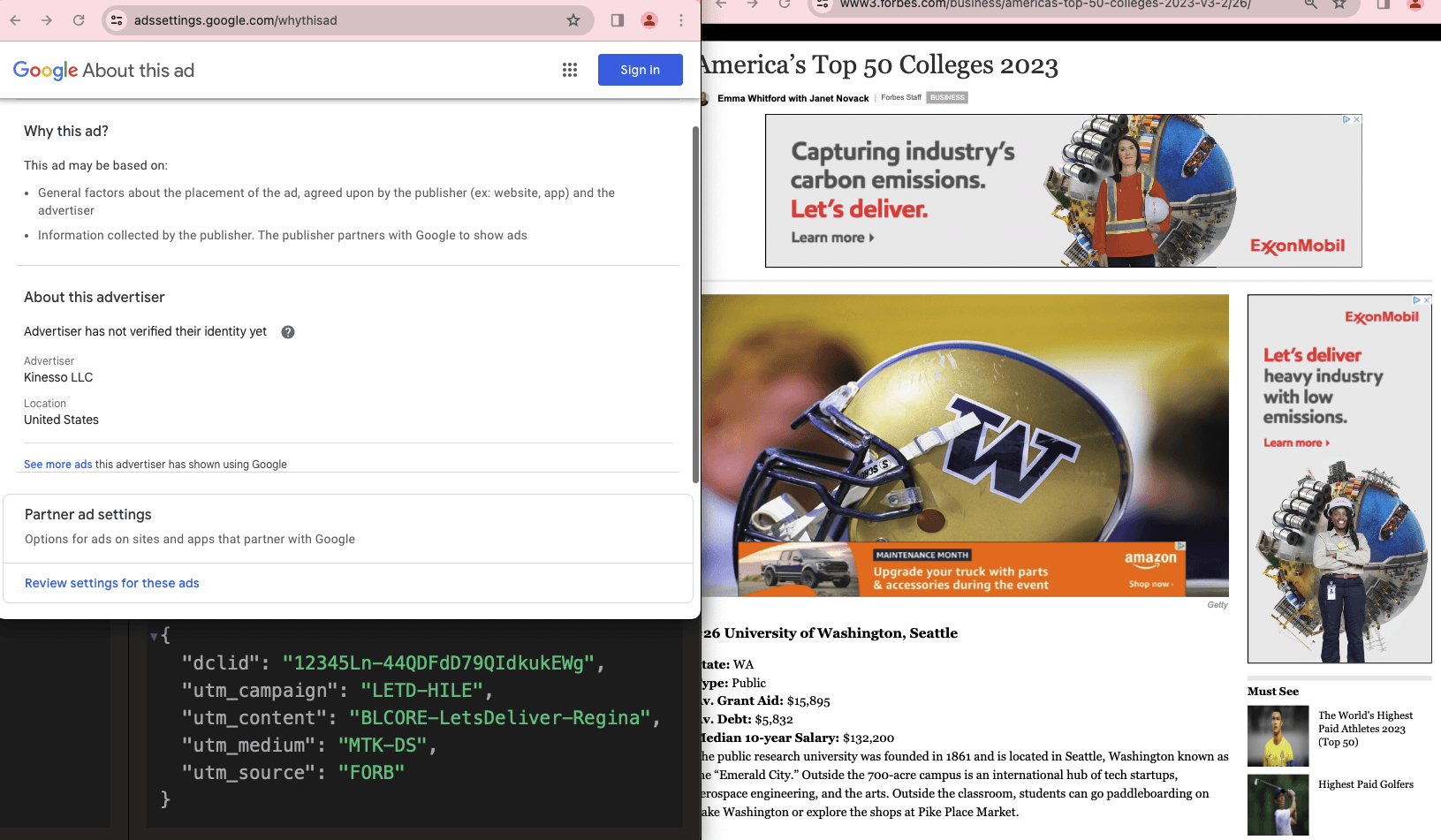

Screenshot of two Exxon Mobile ads observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The “Why this ad?” info modal shows the ads were transacted by Interpublic Group’s (IPG) Kinesso.

Screenshot of a Merck ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The ad source code includes a CM360 pixel that references IPG “Matterkind”.

Screenshot of a Charles Schwab ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The “Why this ad?” info modal shows the ad was transacted by Interpublic Group’s (IPG) Cadreon (now known as Kinesso).

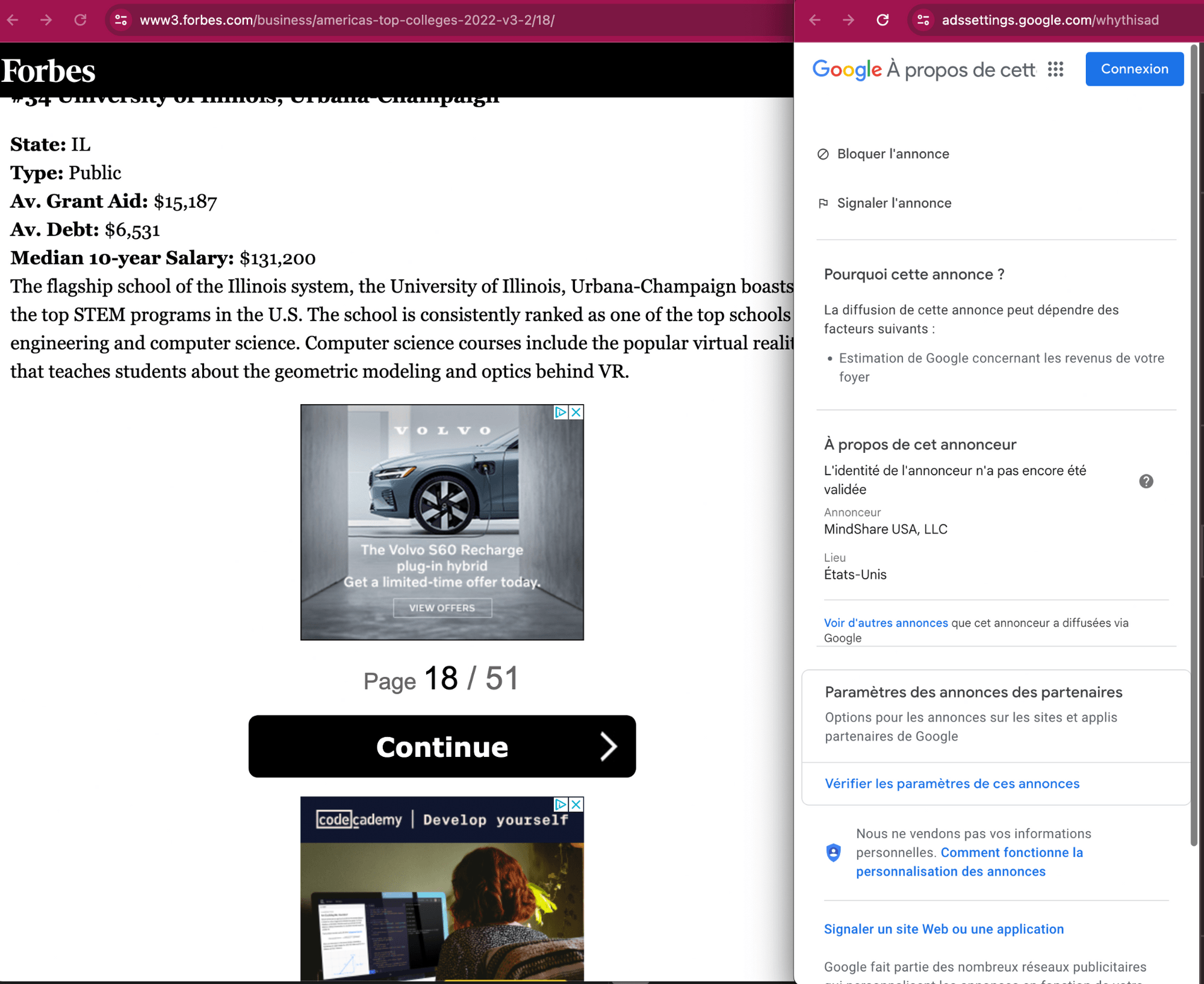

Screenshot of a Volvo car ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The “Why this ad?” info modal shows the ad was transacted by WPP/GroupM’s MindShare.

Screenshot of a H&R Block ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The “Why this ad?” info modal shows the ad was transacted by Gale Partners, a subsidiary of Stagwell.

Screenshot of a Bank of America ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The “Why this ad?” info modal shows the ad was transacted by Publicis Starcom.

Screenshot of three Iowa Lakes Community College ads observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The “Why this ad?” info modal shows the ad was transacted by Forward 3D.

Screenshot of a Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Ontario Canada ad observed on the “hidden” “www3.” Forbes subdomain. The “Why this ad?” info modal shows the ad was transacted by MiQ. The ad contains a CM360 pixel which appears to reference “Cadreon”. Cadreon is the former name of IPG Kinesso.