The vast majority (98.9%) of US Senators and Congressional Representatives are sending certain data points about their constituents, including potentially minors, to for-profit companies such as Google, Facebook, LiveRamp, or Oracle. They are doing this through the use of third party tracking scripts, cookies, and pixels which they have embedded on their taxpayer funded official .house.gov and .senate.gov domains. This includes notable consumer privacy advocates such as Senator Elizabeth Warren, Maria Cantwell, Ed Markey, Josh Hawley, and Ron Wyden, as well as the Senate and House leaders who are in charge of the subcommittees that focus on consumer data privacy and big tech antitrust.

A handful of congressmen also have installed an impressive array of advertising and marketing tech on their .gov websites, sending data about their .gov websites’ visitors to both domestic and foreign data brokers and advertising exchanges such as Avocet, OnAudience, Adobe Demdex, Eyeota, and Weborama. Several congressional websites use more than fifteen times as many third party tracking scripts as ebay.com. Multiple sites also utilize a social media feed widget that communicates with servers belonging to a company based on the outskirts of Moscow, Russia when users open their websites. One congressman even has actual Google Ads iframes embedded on his .house.gov domain.

A few congressmen may be utilizing their taxpayer funded .gov websites to gather data for their re-election campaigns, which may potentially be in violation of Congressional ethics rules, Federal Election Commission regulations, and Constitutional protections against unwarranted government surveillance.

- Introduction

- Results from scanning 537 Congressional .gov websites

- Use of Google Analytics, Facebook Pixel, and other third party trackers

- Use of third party cookies

- Use of third party tracking scripts

- Analysis

- Senate antitrust & consumer privacy committee members

- House antitrust & consumer privacy committee members

- Use of data brokers, audience management, and adtech by Congress

- Sharing of browsing data with foreign companies

- Congressional web pages intended for children

- Privacy policies

- Google Ads iframes loading on a congressional website

- Privacy respecting Members of Congress

- Conclusion

Introduction

If you are a technically minded individual or want to jump straight into interesting findings, I recommend you go directly to the Results and Analysis sections. If you want some background on consumer privacy and how tracking tech works, this Introduction section is designed to provide some background context.

Background

In recent months, there have been increased calls in the US Capitol for strengthening consumer privacy protections and to evaluate the amount of influence tech giants such as Facebook and Google wield over social media, digital advertising, and news dissemination.

These two companies command over 70 percent of the U.S. market share for digital ads. Google and Facebook built their sprawling billion-dollar businesses by providing a myriad of ‘free’ services - social media, content feeds, search results, video, photo sharing, email, and messenger services. They also provide free software tools such as Google Analytics and Facebook Pixel, which website developers can embed within their pages to track user behavior. These consumer and business tools follow hundreds of millions of users around on the internet, placing cookies on users’ browsers and tracking scripts on websites to log peoples’ visits, thereby building detailed profiles of consumers based on their browsing habits and interests. These datasets can then be used to target potential consumers with targeted shoe, vacation, housing, job or political ads.

Google and Facebook’s tracking scripts and pixels are among their most popular ‘free’ software tools, and they appear on websites in every corner of the internet. Even lawmakers calling for greater privacy protections use these tools on their congressional .gov websites purportedly to “improve” their websites. What they may actually be doing is sending their constituents’ data to Google and Facebook, thereby augmenting Google and Facebook’s virtual profiles of users.

There is no shortage of lawmakers on both sides of the aisle clamoring to crown themselves as the champions of our right to privacy online.

Senator Elizabeth Warren (MA), one of the most vocal critics of Big Tech, argues that breaking up Big Tech would drive accountability into their models and give “people more control over how their personal information is collected, shared, and sold.”

Senator Josh Hawley (MO), a rising Republican star, teamed up with Senator Mark Warner (VA) to introduce the Do Not Track Act to allow Americans to opt-out of having their data collected. Sen. Hawley explains, “When a big tech company says its product is free, consumers are the ones being sold. These 'free' products track everything we do so tech companies can sell our information to the highest bidder and use it to target us with creepy ads.” He continues, “Tech companies do their best to hide how much consumer data is worth and to whom it is sold.”

Senator Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) put forward the Mind Your Own Business Act, which he bills as “the strongest-ever protections for Americans’ private data” that “goes further than Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).”

Given these lawmakers’ promises to protect Americans’ online privacy, I was curious how their own, taxpayer funded, .gov websites fare in protecting and respecting users’ privacy? Do their congressional websites, paid for and maintained with taxpayer funds, hold up to their own standards?

A few months ago, while I was working on a chrome extension to collect and analyze digital ads, I noticed many representatives’ websites host dozens of 3rd party cookies and tracking scripts on their .house.gov and .senate.gov websites. This means that the moment you (or a child in your household) visits your Senator or Congressperson’s website, all sorts of information about you--your IP address, physical location, how much time you spend on the page, what browser you’re using, the dimensions of your computer monitor, your computer’s operating system, social media identifiers -- can potentially be sent over to Google, Facebook, and other third party companies.

Context

So how exactly do data brokers or tech companies track users across different internet domains? Here I will provide a quick background on the technical means through which tracking tools operate.

When you open a website such as example.com, your computer’s browser makes a network call over the internet to that domain’s servers, which return an initial HTML document. That document contains instructions your browser parses to show text and styling, as well as further instructions for loading images or dynamic Javascript elements.

By making that initial request to example.com, your device established a quick internet connection that allowed example.com’s servers to see a few pieces of information about your browser, including your IP address. Services such as ipinfo.io allow one to translate a numeric IP address into a geographic location, such as that of your house or the cafe whose WiFi you are using.

If a web developer installed third party javascript files on a website, this serves as an embedded instruction to make your browser fetch additional files from another domain besides the one you are currently perusing. Tracking scripts such as Google Analytics or Facebook Pixel can be loaded this way, and they then act as data sensors, transmitting additional data points back not only to example.com, but also to Google and Facebook’s servers. Certain audience management or data brokers operate on this principle - a developer installs the data broker’s Javascript on their website, and then the data broker can gather information about the website’s visitors and cross-reference with other website’s data, as well as real world data such as credit cars, public records, and real estate ownership records.

In addition to javascript, many trackers load tiny, transparent images referred to as pixels. Facebook Pixel is such an image. When a website configures Facebook Pixel on its pages, that causes users’ browsers to make a network call to Facebook’s servers to retrieve that tiny image. Facebook Pixel can identify a particular user’s Facebook account ID and relay that over the network. This information can then be used to target ads, including potentially political ads. Facebook Pixel can track activity even when a user is not logged into their Facebook account. Facebook’s targeted ad system ‘learns’ from Pixel events as well as custom user profile lists marketers can upload to create a target audience profile.

When your browser fetches images, javascript, or other resources after parsing a webpage’s HTML instructions, it can also receive instructions to store short pieces of text known as ‘cookies’. A first party cookie is one that is set by the domain you are currently visiting - so if you are on example.com, any cookies from example.com are first party. First party cookies can only be read by code sent from example.com.

If your browser receives instructions to store a cookie from Facebook or Youtube, those are third party cookies. First party cookies are frequently used to maintain user login state or save website specific preferences. Third party cookies can serve an additional purpose, which is to allow user’s behavior and usage across different web properties to be tracked. When you navigate to a different website, those third party cookies can be used to identify you as the user that was previously on example.com. Third party cookies can be read on any website that loads javascript or pixels from the third party domain.

Many websites embed social media widgets, such as Instagram photo feeds, Youtube videos, or like buttons. Depending on the precise configuration of these tools, in addition to allowing users to interact with content on those websites, they also relay telemetry and place cookies within the users’ browsers. Website owners have previously been sued in Germany for embedding Facebook ‘like’ buttons on their webpages. A German court found that the plugin “uses cookies that automatically send personal information, such as the user’s IP address and browser string, from the website user’s computer to Facebook when the website is accessed. This transmission of information occurs even if the button is not clicked or the user is not a registered Facebook user.”

As alluded to above, Google Analytics is a ‘free’ Javascript tool for web developers which lets them track certain metrics, such as number of page views and where users are coming from. However, the default Google Analytics settings share information about users with Google via remote network calls from the user’s browser. Google Analytics collects personal data such as the IP address, and shares it with other Google services for advertising purposes. It stores a number of cookies on users’ browsers, some of which persist for ~2 years, and tracks visitors across sessions and webpages through unique user IDs. These IDs and other data points can be used for data sharing and advertising, including alongside Google’s many other adtech tools. Google is currently facing a $5 billion lawsuit in California for using Google Analytics and other tools to track users without their consent even when they are using ‘private’ mode to browse websites.

Google Analytics has an additional feature called ‘Remarketing Audiences’, which enables additional user tracking for targeted advertising. This feature allows website developers to cultivate custom audience lists from their website’s visitors and then follow those users across the internet and target them with advertising on other sites using Google Ads. The tool can connect an individual site session with a user’s ‘real world identity’.

A popular ‘free’ addition to Google Analytics is Google Tag Manager, which enables web developers to track various custom defined events on a webpage, such as clicking a particular button or filling out a form. Google Tag Manager may also allow for cross-site tracking and targeted advertising.

Methodology

I first obtained a list of congressional .house.gov and .senate.gov websites from a public Github repository. Then, I crawled each website during the summer of 2020 with a fresh instance of a headful chrome browser and logged all network calls, cookies set, and resources loaded. Each crawl was done from a US IP address. Initially I used a customized version of Python selenium, while on a second attempt I used a customized version of The Markup’s Blacklight, which runs on Puppeteer and Chromium. I noticed some discrepancies between items collected during the first and second attempts, so I added several additional modules to Blacklight. During each website crawl, the browser would load the page and wait for the network to be idle for ~10 seconds, then slowly scroll down and up along the landing page. Afterwards, it would randomly select two same origin links on the landing page, and navigate to those pages. It would then repeat the scroll process. After the browser would finish navigating, it would close itself, delete all metadata, and then create a new ‘fresh’ instance. All the cookies, network calls, and resources loaded were saved for post hoc analysis.

Network calls were split into same origin or first party requests, such as requests to warren.senate.gov or senate.gov, and third party requests, such as those made to google-analytics.com or any domain other than that of the current webpage.

Following The Markup’s methodology, each third party network request was cross referenced against the EasyPrivacy list, which “contains URLs and URL substrings that are known to be used for tracking”. Third-party domains were also cross-referenced against DuckDuckGo’s Tracker Radar data set to find out who owns those domains and whether they are categorized as being used for advertising related tracking. Some results were manually spot checked using the Small Technology Foundation’s better.fyi/trackers list or Cookiepedia. I also manually cross referenced certain domains against the California and Vermont data broker registries.

Results from scanning 537 Congressional .gov websites

After scanning all .senate.gov and .house.gov domains, I analyzed how many of those websites used common third party tracking tools and how many set third party cookies.

Use of Google Analytics, Facebook Pixel, and other third party trackers

531 out of 537 congressional websites (98.9%) had some kind of observable third party tracking requests, meaning I observed network calls being made by the browser to a domain and URL path that was associated with tracking activity in the DuckDuckGo Tracker Radar or EasyList privacy filters datasets (see interactive Table 1). This excluded calls made to a given domain that was not labeled as tracking or advertising related, such as certain font or image CDNs or Google translate APIs. The median website used four distinct trackers, and the most common third party trackers belonged to either Google or Facebook (see scrollable Table 2). 325 out of 537 congressional websites (60.5%) used some Facebook tracking technology, defined as network calls made to facebook.com, facebook.net, or atdmt.com. The Markup found 33% of top ~100,000 websites loaded with Facebook tracking technology.

| Delegate | Tracking Requests | 3rd Party Cookies | Facebook Pixel | Google Analytics | GA Remarketing Audiences |

|---|

53 out of 537 congressional websites (9.9%) have Facebook Pixels embedded on their webpages, which lets Facebook identify a specific Facebook user account who is visiting a given website and can be used to build audiences for advertising purposes.

502 out of 537 congressional websites (93.4%) use Google Analytics, which allow them to track numbers of visitors and page events. The Markup found that 74% out of the top 100,000 websites load some kind of Google tracking tech. 195 out of 537 congressional websites (36.7%) use Google Analytics’ “Remarketing Audiences” feature, which can be identified by network calls to the stats.g.doubleclick.net domain with a “UA-” Google account identifier prefix.

| DOMAIN | DOMAIN OWNER | # CONGRESSIONAL WEBSITES |

|---|

257 out of 537 congressional websites made network calls to Twitter’s ‘jot’ endpoint, primarily due to the use of embedded social media widgets.

Use of third party cookies

The majority of congressional .gov websites set both multiple first party Google Analytics derived cookies, as well as numerous third party cookies (see interactive Table 3). According to The Markup, the median number of third party cookies set by the ~100,000 most popular websites is three. Ten congressional websites set more than 40 third party cookies upon visiting their webpages, and 76 set more than three third party cookies.

| MEMBER OF CONGRESS | PARTY | DISTRICT | 1ST PARTY COOKIES | 3RD PARTY COOKIES |

|---|

Use of third party tracking scripts

In addition to Google and Facebook tracking scripts and pixels, I noticed network calls to several dozen other domains that DuckDuckGo Tracker Radar considered to be related to advertising or tracking (see scrollable Table 4). 66 Congressional websites have Oracle’s Moat Ads scripts installed, and 69 have Oracle’s AddThis media widget. AddThis’ previous owner, Clearspring Technologies, faced a lawsuit in California over claims that the widget gathered information on users, including children. You can see a detailed, per congressional website, breakdown in interactive Table 4, by clicking on the green expand buttons on the left.

| MEMBER OF CONGRESS | PARTY | DISTRICT | 3RD PARTY TRACKING SCRIPTS |

|---|

Analysis

Senate antitrust & consumer privacy committee members

Virtually all .senate.gov websites use a third party Javascript file from WebTrends which sets a short-lasting third party cookie in users’ browser. WebTrends is a “private company headquartered in Portland, Oregon, United States. It provides digital analytics, optimization and software related to digital marketing and e-commerce.” According to Cookiepedia, the particular cookie acts as a ‘user session identifier’, and is marked as being used for website performance rather than tracking.

The Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation has a Subcommittee on Manufacturing, Trade, and Consumer Protection, which is “responsible for consumer affairs, consumer protection, [...] and data privacy, security, and protection. The subcommittee also conducts oversight on the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)”. The subcommittee consists of 19 Senators, 10 Republican and 9 Democrat.

18 of these Senators’ websites have some form of potential tracking requests, 9 have Facebook tracking tech, 4 use Facebook Pixels, 15 use Google Analytics, and 5 use Remarketing Audiences.

The website of the subcommittee Chairman, Jerry Moran (KS), uses Google Analytics Remarketing Audiences as well as Adobe Tag Manager’s javascript on a specific sub-page. The ranking Democrat on the subcommittee, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (CT) uses Remarketing Audiences and social media widgets that make network calls to Facebook’s servers. Maria Cantwell, who introduced the Consumer Online Privacy Rights Act and is the ranking Democrat on the entire Commerce committee, uses Google Analytics on her webpage and makes network calls to Facebook through embedded social media widgets.

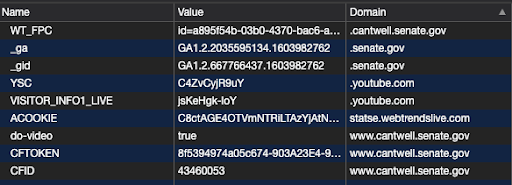

Sen. Maria Cantwell’s webpage setting the _ga and _gid cookies on a user’s browser through Google Analytics. Note that Google Analytics cookies are first party, in that they are shown as coming from .senate.gov

Sen. Maria Cantwell’s webpage setting the _ga and _gid cookies on a user’s browser through Google Analytics. Note that Google Analytics cookies are first party, in that they are shown as coming from .senate.gov

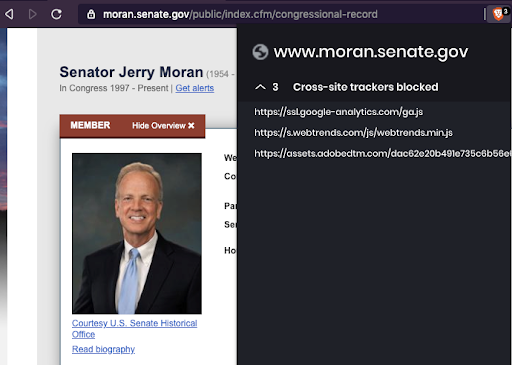

Chairman Jerry Moran of the Senate Subcommittee on Manufacturing, Trade, and Consumer Protection uses Google Analytics and Adobe Tag Manager on his .senate.gov webpage

Chairman Jerry Moran of the Senate Subcommittee on Manufacturing, Trade, and Consumer Protection uses Google Analytics and Adobe Tag Manager on his .senate.gov webpageSen. Ron Johnson (WI) and Sen. Mike Lee (UT) both use Oracle’s Moat Ads and AddThis services.

The Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy and Consumer Rights has led antitrust hearings against Google and other tech giants. The subcommittee consists of 9 Senators, 5 Republican and 4 Democrat. 7 of these use some kind of potential tracking tech, including 6 who use Google Analytics and 1 that uses Facebook Pixel. Sen. Mike Lee (UT) is the chairman of this subcommittee, and as mentioned earlier, uses several adtech and social media services from Oracle as well as Google Analytics. Sen. Richard Blumenthal (CT) is also a member of this subcommittee. Sen. Josh Hawley’s (MO) website makes network calls and sets cookies from a Russian company owned domain, Elfsight, which will be discussed later. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (MN) had no detectable tracking tech on her website (besides the standard WebTrendsLive script present on all .senate.gov websites), making her arguably the most consumer privacy respecting member of the US Senate.

Other Senators meriting a quick mention include Elizabeth Warren (MA), Ed Markey (MA), and Ron Wyden (OR), who have all promoted various privacy related initiatives.

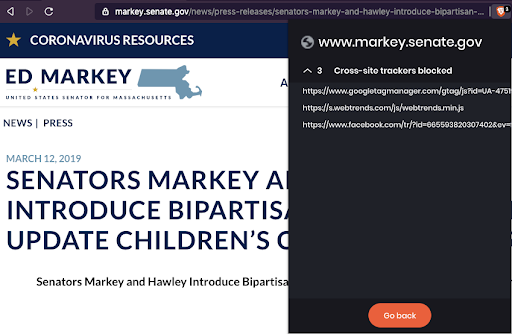

Markey has authored a children's privacy protection law, yet his own website might not respect the privacy of children. When I tried to open a statement Markey made about the “Do Not Track Kids Act”, a press release where Markey criticizes the FTC’s settlement with Youtube over children’s privacy violations, or a press release where he introduces legislation to ‘update children's online privacy rules’, Markey’s website can be seen harvesting and reporting user’s Facebook account IDs via the Facebook Pixel, as well as making network requests to Google’s servers and setting various third party cookies.

Facebook Pixel and Google Tag Manager at work on Markey’s website, where he introduces legislation to protect children’s privacy

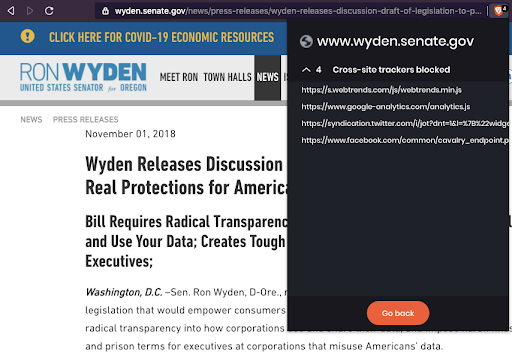

Facebook Pixel and Google Tag Manager at work on Markey’s website, where he introduces legislation to protect children’s privacyElizabeth Warren, who has called for big tech to be broken up and held accountable for information collection, makes use of Google Analytics and several social media widgets which can potentially share user data with tech companies. Ron Wyden, who introduced the “Mind Your Own Business Act” and “Consumer Data Protection Act”, can be seen using sending data to Google and Facebook on his website’s press release about the last bill.

Ron Wyden’s .senate.gov website may potentially send data to companies like Google and Facebook on a press release page that discusses the Consumer Data Protection Act

Ron Wyden’s .senate.gov website may potentially send data to companies like Google and Facebook on a press release page that discusses the Consumer Data Protection ActHouse antitrust & consumer privacy committee members

In the House of Representatives, the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law is the primary institution handling big tech antitrust matters. They have led several recent investigations and oversight hearings for Facebook, Google, and Amazon. The sub-committee consists of 13 Representatives, 8 Democrats and 5 Republicans.

The chair of the entire House Judiciary Committee, Rep. Jerrold Nadler (NY-10), uses Google Analytics Remarketing Audiences on his website. The website of vice chair, Rep. Mary Gay Scanlon (PA-5), uses both Google Analytics Remarketing Audiences and makes network calls to Facebook domains.

The subcommittee chair, David Cicilline (RI-01), has a number of social media widgets embedded on his webpage that make network calls that could enable user tracking. His website not only uses Google Analytics, but it also uses the more invasive Remarketing Audiences feature. The sub-committee chair, Joe Neguse (CO-02), uses both Facebook Pixel and Google Analytics’ Remarketing Audiences feature. All 13 members of this subcommittee use some kind of potential tracking tech on their .house.gov websites, 12 use Google Analytics, and 9 use the Google Analytics Remarketing Audiences feature. 11 of these Members’ websites make network calls to Facebook endpoints that could potentially be used for user tracking. Kelly Armstrong’s (ND) website makes network requests to and sets third party cookies from Simplifi Holdings, a “Local Programmatic Advertising & DSP Platform”.

The House Committee on Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Commerce, which is responsible for ‘privacy matters [and] data security’ consists of 24 Representatives, 14 Democrats and 10 Republicans. Of these, all 24 have some potential form of third party tracking script, 1 uses Facebook Pixel, 23 use Google Analytics, and 13 use Remarketing Audiences. 7 use Oracle’s Moat Ads and/or AddThis social media widget. Michael Burgess’ (TX-26) website uses the adtech platform RhythmOne and the data broker Lotame Solutions. Richard Huson (NC-08) uses Javascript from Simplifi Holdings. Michael Burgess’s (TX-26) website uses more than 25 different adtech or data broker services, including Lotame Solutions, RhythmOne, WarnerMedia, LinkedIn, ID5, Eyeota, Datonics, Bombora, Inmar, TowerData, Intent IQ, Weborama, The Trade Desk, The Nielsen Company, IPONWEB, Tapad, LiveRamp, ShareThis, Weborama, Adobe, Sovrn Holdings, Neustar, and Nativo. This is more than six times the median number of trackers found on the ~100,000 most popular website by The Markup. A number of these are foreign headquartered companies. Weborama, which helps collect and organize data to ‘create audience segments to be activated within the brands' media and marketing ecosystem in order to improve campaign performance” is based in France. ID5, “a centralised ID synchronisation service” which “matches user IDs between publishers, data providers and adtech platforms to enable fast, easy and efficient transfer of user-level data along the advertising value chain” is based in the UK. IPONWEB, which facilitates “engineering of advanced programmatic, RTB, and media trading platforms'', is also based in the UK. The “audience technology platform” Eyeota is based in Singapore.

Use of data brokers, audience management, and adtech by Congress

When I ran this analysis in the summer of 2020, I noticed a number of unusual network calls being made from certain Congressional Members’ websites, which the DuckDuckGo Tracker Radar identified as being advertising and tracking related. Upon further research, I realized that many of the results at the top of Table 3 are related to the use of certain data broker or ad tech tools.

The California State Attorney General maintains a Data Broker Registry and the state of Vermont has a law which similarly requires certain companies that provide data broker services to register with the state. Data brokers can collect, combine, and resell data, which can be used to target political ads, support police law enforcement efforts, perform people searches, and conduct background checks. A manual review of various Congressmen’s webpages did not reveal any indication to users that they were being tracked, and their data sent to third party data brokers.

Rep. Mark Green (TN-7), Dan Newhouse (WA-4), and Roger Williams (TX-25) .house.gov websites make network requests to media6degrees.com, a domain owned by Dstillery, a company registered as a data broker in California. Dstillery provides “custom audience solutions” to “ to maximize the value of customer data”. A previous research study found that Dstillery did not respond to consumer privacy and data release requests.

Rep. Ted Budd (NC-13), Michael Burgess (TX-26), Steve Chabot (OH-1), Ron Estes (KS-4), Francis Rooney (FL-19), Jody Hice (GA-10), Roger Marshall (KS-1), James McGovern (MA-2), Patrick McHenry (NC-10), and Bill Posey (FL-8) use LiveRamp, a registered data broker in state of California. LiveRamp, which is a major data partner for Facebook, was hacked earlier in 2020. Until 2018, LiveRamp was part of the Acxiom Group, which sold data to Cambridge Analytica.

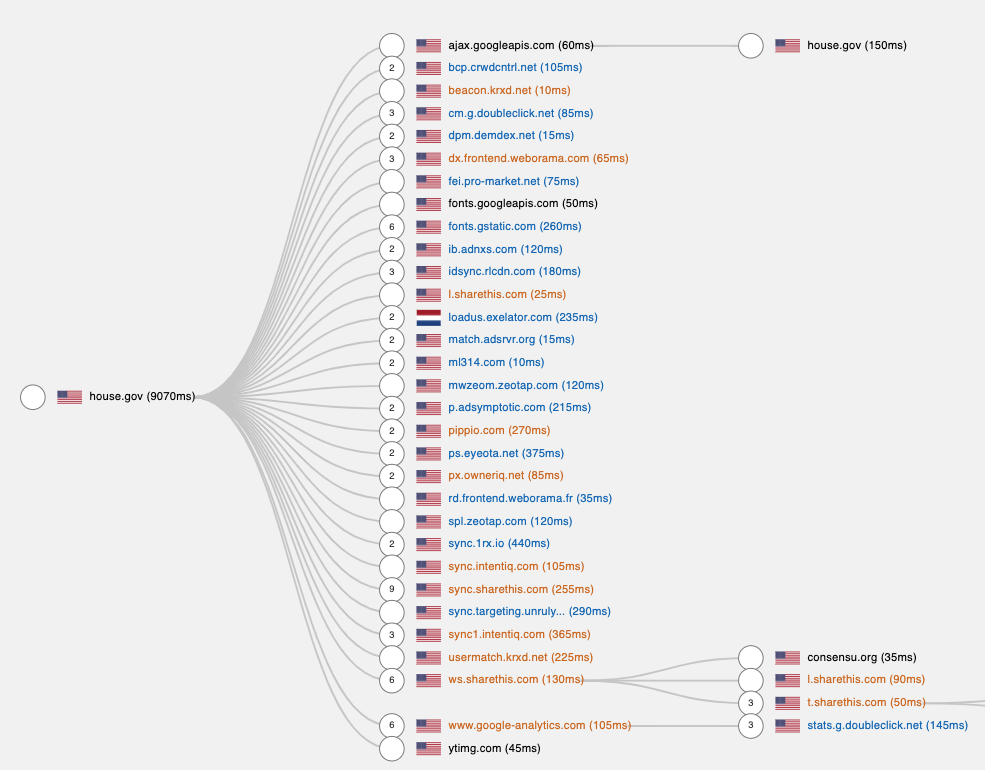

Sankey diagram of network requests made by posey.house.gov. Screenshot taken from Fou Analytics' Page Xray. Network requests are sent to intentiq.com, usermatch.krxd.net, ps.eyeota.net, and other adtech or data broker services.

Sankey diagram of network requests made by posey.house.gov. Screenshot taken from Fou Analytics' Page Xray. Network requests are sent to intentiq.com, usermatch.krxd.net, ps.eyeota.net, and other adtech or data broker services.Most of those Representatives also use TowerData, a “multichannel marketing firm focused on email”, Neustar (a registered data broker in Vermont and California), or Oracle’s BlueKai and Data Cloud, a personal information data management platform. Oracle Data Cloud gives “marketers access to 5 billion global IDs, $3 trillion in consumer transactions, and more than 1,500 data partners available through the BlueKai Marketplace”. A cybersecurity researcher found that BlueKai’s database was unsecured, allowing third parties to access “names, home addresses, email addresses and other identifiable data in the database. The data also revealed sensitive users’ web browsing activity — from purchases to newsletter unsubscribes.” Oracle is facing a GDPR class action lawsuit in Europe for use of third party cookies for ad tracking and targeting without user consent.

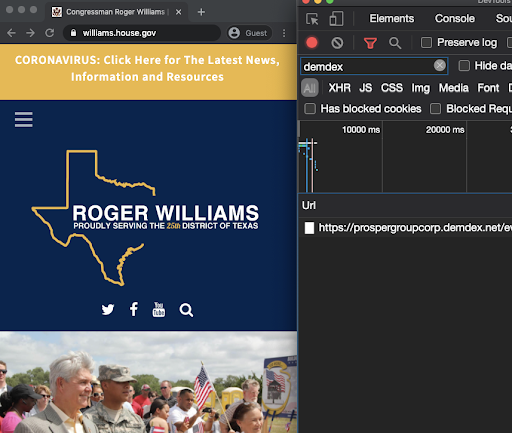

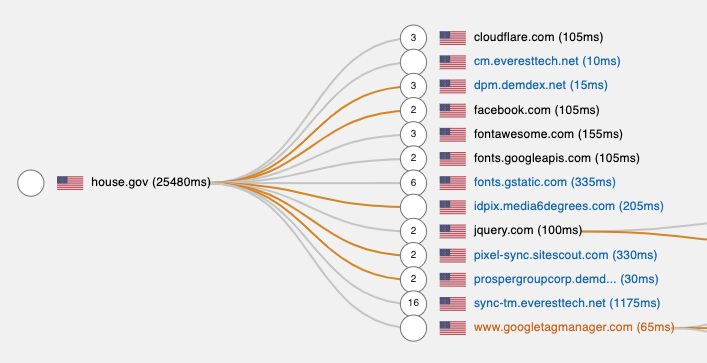

Lastly, the .house.gov websites of Rep. Mark Green (TN-7), Dan Newhouse (WA-4), and Roger Williams (TX-25) make network requests to prospergroupcorp.demdex.net/event. Demdex is a domain used by Adobe AudienceManager, a “data management platform that enables advertisers, publishers, and agencies to build unique audience profiles so you can identify your most valuable segments and use them across any digital channel.” I did a quick search to see who owns that particular subdomain - ‘prospergroupcorp’ is likely Prosper Group from Greenwood, Indiana, a political digital marketing consultancy that works on “Audience/voter targeting” and has worked for Brian Kemp, Ted Cruz, Scott Walker, and Chris Christie’s political campaigns. Prosper Group’s website indicates they worked on “List building, online fundraising, social media management, text messaging, and online advertising” for these campaigns.

Rep. Roger Williams’ (TX-25) and Mark Green (TN-7) .house.gov domain making network calls to prospergroup.demdex.net. Sankey diagram generated with Fou Analytics' Page Xray.

Rep. Roger Williams’ (TX-25) and Mark Green (TN-7) .house.gov domain making network calls to prospergroup.demdex.net. Sankey diagram generated with Fou Analytics' Page Xray.Sharing of browsing data with foreign companies

In addition to the use of domestic data brokers, the house.gov websites of several Congressmen make network calls to multiple foreign data brokers. For example, Zeotap is registered as a data broker in California and is based in Germany. Rep. Burgess, Chabot, Rooney, Hice, McGovern, McHenry, and Posey all have scripts that make network calls to zeotap.com. Many of these same websites make HTTP requests to Eyeota, another registered data broker which is based in Singapore, or Weborama, a France based data management platform that aids with behavioral targeting.

The use of so many different adtech and data management platforms does beg the question how these Members of Congress are paying for this technology, which in some cases can cost thousands of dollars at a minimum.

Lastly, I noticed several Congressional websites were making network calls to IP addresses based in Russia or domains registered to a company in Russia.

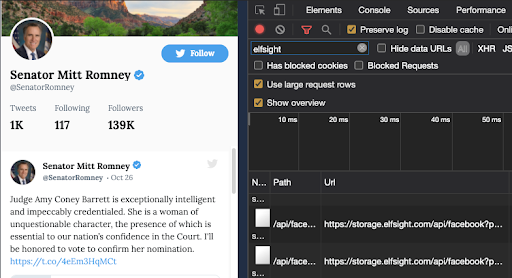

Sen. Mitt Romney (UT), Tina Smith (MN), Marsha Blackburn (TN), Mike Braun (IN), Josh Hawley (MO), Cindy Hyde-Smith (MS), Kelly Loeffler (GA), Rick Scott (FL), and Rep. Brian J. Mast (FL-18) websites make HTTP requests to elfsight.com or instacloud.io. A WhoIs lookup reveals elfsight is registered to Vladimir Fedotov in Tula, Russia. Elfsight provides a social media embed widget which allows developers to easily display and send certain social media data. While writing up this analysis, I noticed that Elfsight domain servers are now behind a Cloudflare IP address based in San Francisco.

Sen. Mitt Romney’s webpage making HTTP requests to Elfsight, a company based in Tula, Russia

Sen. Mitt Romney’s webpage making HTTP requests to Elfsight, a company based in Tula, RussiaCongressional web pages intended for children

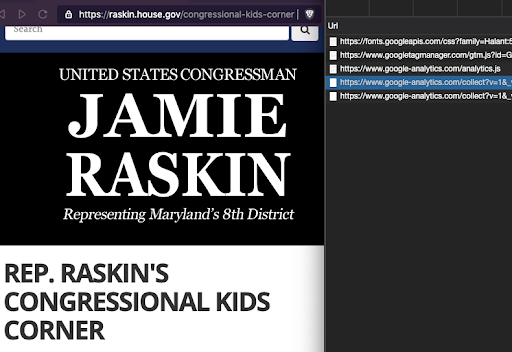

Several Members of Congress have dedicated pages on their websites intended for children. These websites also make network requests which could be used for tracking. For example, Rep. Jamie Raskin (MD-8), has tracking scripts on the “Kid’s Corner” of his webpage, which were shown to be sending multiple tracking requests with data to google-analytics.com/collect

Rep. Jamie Raskin's (MD-8) website's "Congressional Kids Corner" making network calls to Google Analytics endpoints

Rep. Jamie Raskin's (MD-8) website's "Congressional Kids Corner" making network calls to Google Analytics endpointsRep Louie Gohmert (TX-1) and Pete Olson (TX-22) also include web pages intended for kids which have potential third party tracking scripts. Unfortunately, none of these pages warn children or parents that certain data is sent from their browsers to third parties upon using these webpages (though there is further information provided in those website’s respective privacy pages).

As mentioned earlier, 69 congressional webpages have Oracle’s AddThis media widget. AddThis’ previous owner, Clearspring Technologies, previously faced a lawsuit in California over claims that the widget gathered information on users, including children.

Privacy policies

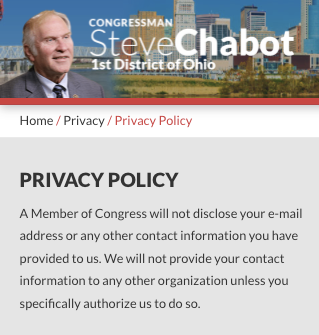

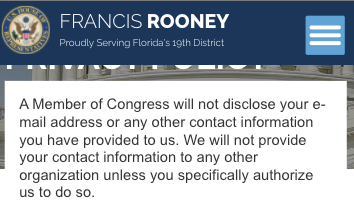

Given the heavy use of third party tracking scripts by Congressional websites, as well as the use of data brokers by certain Members of Congress, I was curious how much information is conveyed to users in their privacy policies. Though I did not do a comprehensive review, I did find some interesting anecdotes.

Rep. Steve Chabot or Francis Rooney’s privacy policy pages do not disclose the use of ~30 third party tracking scripts or domestic and foreign data brokers in any way.

Rep. Steve Chabot and Francis Rooney's .gov websites privacy policies do not disclose the potential transmission of user data to domestic and foreign data brokers and ad tech companies

Rep. Steve Chabot and Francis Rooney's .gov websites privacy policies do not disclose the potential transmission of user data to domestic and foreign data brokers and ad tech companiesSen. Elizabeth Warren’s privacy policy page states her “website does not use 'cookies' or other means to track your visit to my site in any way”, despite the fact it makes network calls to Google’s servers and loads several first party and third party cookies.

Several dozen Congress person’s privacy policy pages do disclose the use of Google Analytics. However, I did not see any privacy pages that specifically discuss the collection and transfer of data from minors who visit a given Congressmen’s website, particularly the “For Kids” sections. Additionally, Google’s terms and conditions require website operators to disclose when data is collected with the Remarking Audiences feature to connect browsing data with a user’s real world identity. However, my manual sample of Congressional privacy policies did not reveal any disclosures about the use of this feature. None of the websites I reviewed had cookie consent banners.

Google Ads iframes loading on a congressional website

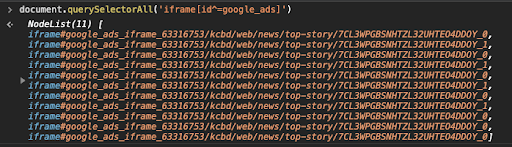

One strange observation that I could not understand was why there are Google Ads iframes loading on Rep. Jodey Arrington’s (TX-19) .house.gov website. For example, when I open this page, and use Chrome developer tools to run this command to identify Google Ads iframes, I find there are 11 hidden frames loaded. Note that no actual ads load in these frames. Interestingly, the ads iframes follow a certain naming convention - you can see a reference to ‘kcbd/web/news/top-story’. This is likely a reference to KCBD NewsChannel 11, which is located in Lubbock Texas. It’s not clear why KCBD’s ad iframes would be loading on a government webpage.

Hidden Google Ads iframes loading on Rep. Jodey Arrington’s (TX-19) congressional website

Hidden Google Ads iframes loading on Rep. Jodey Arrington’s (TX-19) congressional websitePrivacy respecting Members of Congress

Given the abundance of tracking scripts and third party cookies on many congressional websites, I was curious if there were any pages that chose to avoid using such tech. The top two ‘paragons’ of consumer privacy that I could identify were Rep. Harold Rogers (KY-5) and Jackie Speier (CA-14). These websites do not use any Google Analytics or Tag Manager, nor any third party provided social media feed widgets. Whereas many Congressmen choose to use tools like Elfsight or tools provided by Google, Twitter, or Facebook to embed Youtube videos, like buttons, and tweets, Speier’s website uses custom built code. This code lets her host various content from her Twitter account or Instagram photos without making API calls or HTTP network requests to third party domains. She maintains a copy of all of her Instagram photos on her own domain, and then serves those photos to website visitors through her own content delivery network. If users choose to see Speier’s social media accounts, they must click on a custom made link that redirects them to those separate web pages. It would be commendable if other Members of Congress followed Rep. Speier’s website design, with one caveat. Unfortunately, it seems her privacy policy page is broken at the time of writing.

It is interesting to note that the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s San Francisco headquarters borders Jackie Speier’s congressional district.

Conclusion

Caveats & Limitations

The scans in this analysis were carried out in June and September of 2020, and represents a static snapshot of network and cookie activity on various .house.gov and .senate.gov websites. It is possible for many of the scripts and pixels observed during the course of this analysis to be removed or changed at any point by the websites’ administrators. I encourage users to use tools like The Markup’s Blacklight, Phantom Analyzer, Fou Analytics’ Page XRay, or Ghostery Insights Beta browser extension to independently and periodically validate the observations made in this study.

The behavior of various tracking scripts or websites may change in response to a number of variables, such as user agent, operating system, or presence of pre-existing cookies. I used a fresh browser instance on each website scan, which was devoid of any local storage or cookies. I used one US IP address for this analysis - it is possible that certain tracking scripts or cookies are only set if a website detects a user is browsing from a given congressional district. I was not signed into Facebook, Gmail, or Twitter while running this analysis - it’s possible additional or different data is collected if a user navigates to a given website with these accounts open.

This analysis made heavy use of external datasets (such as the DuckDuckGo Tracker Radar) to determine which network calls or cookies are likely associated with tracking behavior. This may lead to both false positives as well as false negatives. I found a few domains that, upon manual inspection, were clearly related to ad tech companies, but not included in the Tracker Radar.

I observed many HTTP requests from my browser to various third party domains while browsing Congressional websites and cross-referenced these with various tracker datasets, but cannot make any definitive statements regarding data collection or privacy matters. It is possible for example that a third party server is immediately discarding or ignoring requests coming from these .gov domains, or adding some kind of server-side (or client-side) anonymization. Google Analytics has a feature to turn on IP Anonymization. I was not able to determine whether or not any congressional websites currently utilize that feature. However, to truly prevent cross-site tracking, those websites would also need to disable cookies from Google Analytics, which I saw was not the case.

Discussion

This exploratory analysis, while certainly not comprehensive, revealed several important points.

Firstly, a large number of elected government officials are using taxpayer funded resources to collect data about individual citizens and potentially send that data to third party for-profit companies. Of the 537 Congressional websites analyzed, 93.4% use Google Analytics, 36.7% use Google Analytics’ “Remarketing Audiences”, 9.9% use Facebook Pixel, and 60.5% had network calls to various Facebook domains which could potentially be used for tracking. Several Representatives had various data broker related Javascript files installed on their congressional websites, including from foreign companies. 69 used the AddThis widget, which was implicated in a lawsuit in California over claims that the widget gathered information on users, including children. Contrast this with the European Parliament’s website, where no trackers can be found.

In many cases, this data collection and sharing appears to have been done without user knowledge or consent, such as consent banners or forthcoming privacy policy pages. Because these are .gov websites, they ostensibly constitute part of the federal government. This may raise questions relating to constituents’ Constitutional rights and protections.

The US Supreme Court recognized the right to privacy in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). In this case, the Court “used the personal protections expressly stated in the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments to find that there is an implied right to privacy in the Constitution.” It is not clear whether or not this case would apply to the specific type of digital surveillance and data sharing seen on congressional .gov websites.

Secondly comes a question relating to consumer safety. Some of the third party tracker companies discussed in this study have already been breached in previous cybersecurity incidents. If Congressional officials are sending user data to these companies and another breach were to occur, this would make them complicit in citizen’s identifiable information being leaked. Additionally, the use of foreign data brokers and foreign-sourced social media widgets may have additional legal and security ramifications.

Thirdly, one may consider the matters of congressional oversight and effectiveness. As the various House and Senate committees investigate tech companies for anti-competitive practices and privacy violations, they (or their advisors) must understand how various technologies operate and help those companies' business models. If these Representatives and Senators are using free tools provided by those very companies on their own .gov websites, thereby inadvertently leaking certain identifiable information about constituents, then they are strengthening the ‘walled data gardens’ that power those businesses. If a Senator makes a claim on her website’s privacy policy page that states it does not use any cookies, but this is demonstrably false, one may wonder if the Senator’s staff will be able to identify more subtle or nefarious forms of digital tracking, such as canvas fingerprinting.

Fourth, comes the matter of ethics, financing, and conflicts of interests. The vast majority of Members of Congress engage in some form of political fundraising and allocate money to political ads. Advertising platforms like Facebook and Google operate more efficiently when operators feed in specific targeting data, such as custom audience lists. Brad Parscale, the Trump campaign’s digital strategist in 2016, tweeted that their campaign on Facebook was “100x to 200x” more efficient than the Clinton campaign. The reason for this became clear after whistleblower Christopher Wylie revealed that part of the Trump campaign’s data analytics team, Cambridge Analytica, “used personal information taken without authorisation in early 2014 to build a system that could profile individual U.S. voters, in order to target them with personalised political advertisements.”

Should elected government officials be allowed to use tools like Facebook Pixel or Google Remarketing Audiences to build target lists for political ad campaigns, on their taxpayer funded, official-use, .gov properties? This would put incumbents at a distinct advantage over political challengers - the incumbents can spend years gathering data on their .gov websites to figure out which constituents spend a lot of time reading their press releases about immigration, taxation, criminal justice, or other sensitive issues, thereby constructing psychographic profiles.

Several Members of Congress use over two dozen different data brokers’ code on their .gov websites. Rep. Mark Green (TN-7), Dan Newhouse (WA-4), and Roger Williams’ (TX-25) websites likely make network requests to Prosper Group, a political campaign ‘list building, online fundraising, and digital advertising’ company.

The Senate ethics regulations state that "Official resources (Senate space, equipment, staff time, and supplies) should not be used to assist campaign organizations.” House ethics regulations state that "internal office files...may not be used for campaign or political purposes...the office files may not be reviewed to obtain names of individuals to solicit for campaign contributions." This would suggest it may be a violation of Congressional ethics rules to use .gov websites for campaign audience list building, via tools like Facebook Pixel, Google Remarketing Audiences, or data broker and audience management services.

Additionally, one may wonder how Members of Congress are paying for a lot of the non-free marketing, data broker, and audience management tech. For example, several Members of Congress use Oracle’s Moat service. Moat may cost $2,500 per month. If the other adtech services are similarly priced and a Member of Congress has 25 of them installed on his web page, he may be spending more than $60,000 on adtech and data broker services per month. Is this javascript code paid for by official, taxpayer derived funds, or by political campaign funds? I tried to look through the Congressional Statement of Disbursements to see if I could identify any payments to data brokers or digital advertising companies, but was unable to identify any. House ethics regulations state that Members’ Representational Allowance “may not pay for campaign expenses or political expenses (or any personal expenses).” The Federal Election Commission’s Campaign Law document mentions a “Prohibition against use of certain Federal funds for election activities”, but it is not clear whether that would apply to the use of .gov websites for campaign purposes.

Congressmen are right to want to engage directly with their constituents and keep them up to date on the important work they are doing. However, it’s critical to find a proper balance between the need to communicate with constituents and the need to respect their privacy (especially for minors).

I would encourage there to be more public discourse on whether elected representatives be allowed to use taxpayer funded resources, such as their .house.gov or .senate.gov domains, for sharing data with for profit companies or for building datasets that can then be used for running targeted political ad campaigns.

In the United States, there exists a ‘congressional franking privilege’, dating from 1775, which “allows Members of Congress to transmit mail matter under their signature without postage. Congress, through legislative branch appropriations, reimburses the U.S. Postal Service for the franked mail it handles. Use of the frank is regulated by federal law, House and Senate rules, and committee regulations.” I encourage Congress to evaluate whether similar regulations are warranted to govern how Congressmen can utilize their official .gov domains, including whether they should be allowed to utilize their websites to build datasets about their constituents that could help them in an election - something that could put incumbents at an advantage over political challengers.

Possible future investigations by journalists or legal scholars

I am not a legal scholar or investigative journalist, but I realize that this analysis raises some additional questions which may be interesting to pursue by more qualified individuals:

- Why are certain Congressmen using data brokers or ad tech services on their .gov websites? What data are they sending to these companies? How are they paying for all the data brokers or ad tech services, like Moat or LiveRamp? The Congressional Statement of Disbursements and political campaign spending data may offer some clues. It may also be possible to submit a FOIA request to find out what information has been gathered through these services, and what information was sent to these companies. This may be of interest to the ACLU or EFF.

- Are there any cybersecurity or policy implications of Congressmen using foreign derived code from a Russian company on their .gov websites (such as Elfsight)?

- Why are certain congressmen using Prosper Group’s Adobe Audience Manager script on their .gov websites?

- Are any Congressmen using their .gov websites to guide Facebook political ad campaigns? Perhaps Ad Observatory or Who Targets Me can aid in answering this by parsing political ad UTM data.

- Does the lack of accurate privacy policies, consent banners, and data sharing disclosures on official .gov websites violate CCPA or other privacy frameworks? Are there any implications specifically related to data collecting and sharing about minors?

- Why does a Texas congressman have Google ad iframes on his .gov website?

Take away points & recommendations for Congress

- Most Members of Congress, including those trying to regulate big tech, use third party tracking scripts on their taxpayer funded .gov websites

- Several Members of Congress send data about their .gov websites’ visitors to dozens of data brokers, including foreign based companies

- Some Congressmen may be using their taxpayer funded .gov websites for custom audience building and political ad targeting

- Members of Congress should consider switching to privacy focused, cookie-less analytics tools, such as Fathom Analytics, self-hosted Plausible Analytics or cookie-disabled, on-premise Piwik Pro

- Congressmen should follow Rep. Jackie Speier’s example, and avoid using third-party provided social media feed widgets

- Members of Congress should remove tracking tech from “For Children” pages or other sections dedicated to children